Home where my host family lives in Garrison, MD, in a post-Civil War freedman’s settlement

First day, Sunday, March 20th

So here I am on the East Coast, commencing my Frederick Douglass history of ideas travel adventure in earnest! I’m thrilled and know I’ll learn and see a lot since I have so many sites I plan to visit already and know I’ll discover more as I go along.

I wake up still undecided whether to begin my Douglass explorations on the East Shore of Maryland or in Baltimore proper. I was leaning toward the Shore to keep my account more chronologically aligned with Douglass’s life, but inclement weather, the Maryland Historical Society’s open hours, a lost document, and a bit of oversleeping decided for me: a delayed start made it best to keep today’s journeys closer to home away from home. So, Baltimore it is!

Fell’s Point, Baltimore, Maryland

Aliceanna and Durham Streets, Baltimore, Maryland

In a very important way, it’s actually fitting to begin with Douglass’ life here in Baltimore, centered in the waterfront district of Fell’s Point, since this is where Frederick Douglass had one of the most formative experiences of his life.

It happened in a ‘spare, narrow house at the corner of an alley’, Happy Alley, off Alliceanna Street at S. Durham. This was Douglass’s first home with the Hugh Auld family, composed of shipbuilder Hugh, his wife Sophia, and their little son Tommy. Frederick Bailey, who adopted the last name Douglass after fleeing slavery, was a child of just seven or eight himself, was imported from the plantation to be Tommy’s companion and body servant.

There used to be a sign marking this street corner as a Frederick Douglass historical site, but it’s disappeared (you can see the two silvery clamps still strapped under the street name signs). Perhaps people in the neighborhood were tired of being bothered by tourists asking where the exact house is. I have no shame, so I bother a young man with my inquiries. He doesn’t happen to know about that historical tidbit but is interested to hear the story; he happens to pass me by again a little while later, pulls over, and asks for the website so he can check in later and see what I find out, so I know he isn’t just being polite; he certainly is very kind.

Site of Frederick Douglass’ home with the Aulds at Aliceanna and S. Durham, Fell’s Point, Baltimore, MD

And another nice person, a woman entering her home in the very new-looking building on the southeast corner of Alliceanna and S. Durham does know, however, and confirms that building below, as far as she knows, stands on the very site of the old Auld house. She, for one, hopes the sign will go back up.

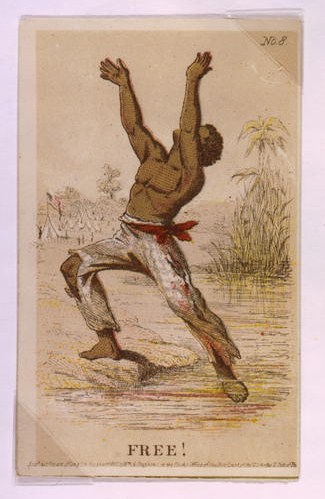

So back to that formative experience: Sophia Auld thought it would be a good idea to teach Frederick how to read since he was companion and body servant to the young son of the household and could thus aid in his education. But when Hugh came into the room and saw her teaching Frederick his letters, he stopped her, telling her in his hearing that ‘[he] should know nothing but how to obey his master …if you teach [him] how to read, there will be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave…’ As Douglass later recalled, this is the moment he realized the full inhumanity of the slave system, and knew exactly what he needed to do. No enforced ignorance for him!

Lancaster St, end where Gardiner’s and Beacham’s shipyards used to be, Fell’s Point, Baltimore MD

Then I head down to the end of Lancaster St, about where Frederick worked at James Beacham’s shipyard in 1826, close to William Gardiner’s shipyard where he received more advanced training, upon returning to Baltimore in 1836 after three years back on the East Shore. He had another formative experience at Gardiner’s which I’ll tell you about shortly. Frederick worked on many shipyards and became a skilled caulker over time, earning him enough wages that Hugh was willing to let him keep some, unaware Frederick was saving up to start a new life as a free man one day.

Boats docked at end of Lancaster and Thames Streets, Fell’s Point

I head west on Thames St. At number 12 or 13, Frederick purchased the first book he ever owned at Nathaniel Knight’s shop at 28 Thames St, The Columbian Orator. The buildings are numbered very differently now, and at the time I write this post, I’ve yet to find an early atlas with street addresses. Fell’s Point is clearly a moneyed area, and large sections of Thames St has been built over with luxury condos, especially on the waterfront side. The other side of the street retains more of its older buildings, and all is very well kept and very charming.

A view of Thames St, Fell’s Point, Baltimore MD

I continue on to the very end of Thames St, heading west to the Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park and Museum.

Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park and Museum, Fell’s Point

Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Museum Sign, Fell’s Point

The sculpture I find here of his head, though striking, looks a little odd just sitting on the ground as it is; I find myself instinctively looking around for the body it fell off of. Perhaps they’ll give it a new setting at some point.

Frederick Douglass sculpture at Maritime Park Fell’s Point

Frederick Douglass sculpture at Maritime Park, with sign

Then I head right, around to Philpot St, where Frederick also lived with the Auld family (they moved around the Fell’s Point neighborhood a few times). The Maritime Park Museum actually faces onto it at least as much as it does onto Thames. Here, little Frederick obtained the help of his playmates to build on the fragmentary education he had received from Sophia and really learn to read. Some neighborhood boys helped him out, and though he never named them in his narrative for fear they’ll be criticized for this, he thanked them anonymously.

Corner of S. Caroline and Block St by Philpot St, Fell’s Point

The little loop of a street which remains that’s still called Philpot St on Google Maps, though there are no identifying street signs, is at the west end of Thames behind Block and S. Caroline. It curves around to where the Maritime Museum and Park overlook the harbor, and you can see Domino Sugars factory in the background across the water. The area where the Auld house was, and perhaps where Frederick played and read with his friends at Durgin and Bailey’s shipyard, is now flattened, with all signs that there ever was a street here, let alone a neighborhood, obliterated and under new construction.

Then I backtrack a little on Thames towards Bond St. If you look closely, you can see this view of Bond St is at Shakespeare St; Frederick grew to love William Shakespeare.

Bond St at Shakespeare St, Fell’s Point

The occasion which took Frederick to Bond St, and which takes me here next too, was a sad one. Since he had become a skilled caulker at Gardiner’s shipyard, his work was very much in demand, especially as an enslaved black man who commanded lower wages than skilled white workers. Baltimore’s shipyards employed many skilled black workers on its busy waterfront, paying them all lower wages, and the white workers felt deeply resentful at this threat to their livelihood. So one day, when Frederick was perhaps sixteen, he was severely beaten by four of his coworkers. Auld was very angry, both because, as Frederick believed, he was genuinely concerned about his well-being and considered what they had done cruel and unjust, and, of course, he did not want his prized source of income to lose his ability to work. So he accompanied Frederick to magistrate William Watson’s office on Bond St. Again, as of this date, I can find no specific street address; when and if I do, I’ll let you know.

But to Auld’s chagrin, Watson refused to arrest the men or do anything about the crime at all: although the evidence a crime had been committed was presented in Frederick’s own battered face, only a white man’s testimony was legally admissible. The indignity and injustice of this were yet more striking evidence for Frederick that slavery was a great evil, strengthening his conviction that he must find a way to gain his freedom.

Then back up Bond to Aliceanna again, to grab a snack and better wifi connectivity at Cafe Latte’da, a punk rock-y comfy little hole in the wall coffee shop. It’s right around the corner from Jimmy’s Restaurant and Fountain Service on S. Broadway, where I had begun with a delicious breakfast of tater tots topped with pulled pork and cole slaw. If you’re like me and love comfy, well-established eateries with down to earth food and atmosphere, I recommend these two.

Fell St at Thames and Ann, Fell’s Point, Baltimore MD

Then back to Fell St at Thames and Ann, which I had overlooked on my first go-round, but it’s no problem since the waterfront part of Fell’s Point is pretty small and very walkable. Frederick lived on Fell’s St with Hugh Auld when he returned to his service in Baltimore in late 1836. Again, Douglass gave no address in his memoirs. Hugh thought he’d be less likely to try to escape if he had more interesting employment in an environment which better suited him, enjoying more independence through retaining part of his wages and eventually, living in a place of his own. At this point, Frederick had become an expert caulker and could command much better wages despite his race and status as a slave. When Frederick did live on his own for awhile, there was an episode where Frederick didn’t return from a weekend outing to the Fell St house in time, and Auld was enraged. He threatened to take away the independence he had granted Frederick up to this point and to make him move back home.

Thames St Park bordered also by Lancaster and Wolfe, Fell’s Point

Since I’m back near the east end of Thames, I go back towards the end of Wolfe Street since I had found another secondary resource, a Baltimore Sun article, on my coffee break. I’m looking again for the site of Gardiner’s shipyard where he was beaten by his co-workers. According to the article, ‘William and George Gardiner’s shipyard [was] on the north-east corner of Lancaster and Wolfe Streets’. It’s not at the water’s edge now; the waterline at Fell’s Point has been changed quite a bit in many places over the years as it’s been filled in and built over. Beacham’s, as I described earlier, would have been nearby, around the corner to the north. There’s this little park called Thames St Park, bordered also by Wolfe and Lancaster; perhaps this is the site of one or part of both of those shipyards.

Douglass Place, 500 block of Dallas St, Fell’s Point Baltimore MD

Douglass Place with engraved marker, Fell’s Point

Next, I head for a site associated with Douglass many years later in his life. I walk north on S. Durham St, passing Douglass’ first home site with the Aulds again, then left (west) on Aliceanna towards S. Dallas St. I find that the stretch of Dallas between me and the 500 block of Dallas near Fleet St where I’m headed is built over, so I go back up Bond to go around. I find what I’m looking for: a little row of brick houses, where an engraved cream stone in the larger of the red brick buildings confirms this is indeed ‘Douglass Place’. Douglass built these in the early 1890’s as quality, affordable rental housing for black residents.

Historical Plaque at Douglass Place, Fell’s Pt

Billie Holliday house at 219 Durham St, Fell’s Point

On my way out from Fell’s Point proper, I decide to swing by a site only very tangentially linked to Douglass. The lady who confirmed the location of the Aliceanna St house directed me to a home where Billie Holiday grew up at 219 Durham St. I love Billie Holiday, as I’m sure you do too, so I’m thrilled to make this discovery. Holiday, as you remember, sang ‘Strange Fruit’, a stark and haunting song about lynching that was very controversial when she recorded it in the late 1930’s but well loved, and her performance of this song is among the very best. Douglass became an activist in his later years against lynching…. more on that in a future post.

The Wharf, formerly known as Smith’s Wharf, at the end of Gay St, Inner Harbor, Baltimore MD

Then I head towards the Inner Harbor, west towards downtown, to the wharf which used to be called Smith’s Wharf. It’s described in an old document as located at the south end of Gay St. ‘run[ning] north and south, from the east side of Gay St dock…’, now at Pratt, assuming that where the water meets the shore has not changed dramatically, though it’s not really a safe assumption. It’s just that I mostly have the current shoreline to follow, with atlases from young Frederick’s time so scarce.

Wharf at Gay and Pratt, formerly Smith’s, Inner Harbor, Baltimore MD

This is where little Frederick first arrived in Baltimore, diverted from his likely destiny as a plantation slave to a better one working in the city, though this was no guarantee of better treatment. Though city slaves often enjoyed a better standard of living in the city, Douglass tells of slaves in neighboring homes in Fell’s Point who were treated very cruelly. But on that day in the mid-1820’s, as Frederick watched the city shore draw near, he was thrilled at the prospect of a new and easier life than that of his deprived, if somewhat carefree, childhood as a plantation orphan.

Maryland Historical Society Museum, Celebrating the 15th Amendment Plaque in the Civil War Exhibit

Then to my last stop, the Maryland Historical Society downtown, to see what they have on Douglass. I don’t find much, as the library is closed, though the museum is open. I am excited, however, to find a plaque with a photo of an event I want to discover a location for but haven’t yet. In 1870, Douglass gave a speech before a crowd of about 10,000 people in Baltimore in celebration of the passage of the 15th Amendment, and as it turns out, the celebratory parade ends at, and the celebrations culminate, at the War of 1812 memorial tower called the Battle Monument at E. Fayette and N. Calvert; you can see its column to the right. As luck would have it, an unsuccessful search for another site (I’ll tell you about it in the next post) happens to take me to thus very same place; when going through and studying my photos afterward, I’m excited to make this discovery! Here’s the site today; as you can see, it looks very different, except for the Monument itself.

Battle Monument at E. Fayette and N. Calvert, Baltimore MD

So ends my first day of following the life of Frederick Douglass on the East Coast, and it’s been a thrilling one. Coming up next: a day on the East Shore of Maryland, his birthplace and towns where he spent much of his early life. Stay tuned!

*Listen to the podcast version here or on iTunes

~ Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and is ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and Inspiration:

‘Battle Monument‘. In Wikipedia, The Free Enclyclopedia. Encyclopedia.

Douglass, Frederick. The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Re-published 1993, Avenal, New York: Gramercy Books, Library of Freedom series.

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom: 1855 Edition with a new introduction. Re-published 1969, New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

‘Douglass Terrace – Dallas Street North of Fleet Street’. BaltimoreMD. com

‘Eastern District‘. Baltimore City Police History.com

Foner, Philip S. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. 1-4. New York: International Publishers, 1950.

‘Historical Sign Marking Where Frederick Douglass Lived as a Slave in Fells Point at Durham & Aliceanna‘. (photo) What I Saw Riding My Bike Around Today blog

Kelly, Jacques. ‘2 Neighborhoods Show City’s Gems of Black History‘. Feb 19, 1993, The Baltimore Sun website

Lakin, James. The Baltimore Directory and Register, for 1814-15. Baltimore: J.C. O’Reilly.

McFeely, William. Frederick Douglass. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991.

Papenfuse, Edward. ‘Recreating Lost Neighborhoods: The House on Ann Street, Fells Point, Baltimore City, Maryland‘. Reflections by a Maryland Archivist blog

‘Separate is Not Equal: Brown vs. Board of Education‘. The National Museum of American History website, by the Smithsonian

Shopes, Linda. ‘Fells Point: A Close-up Look At Baltimore’s Oldest Working-class Community’. Nov 24, 1991. The Baltimore Sun website

Troy, Davis. ‘The Story of the 15th Amendment in Maryland‘. Maryland.gov

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, and The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series 2: Autobiographical Writings. 3 volumes. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, and The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series 2: Autobiographical Writings. 3 volumes. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999

As you may know, dear readers, I’m embarking on the travel portion of my fifth philosophical-historical themed adventure in mid to late March.

As you may know, dear readers, I’m embarking on the travel portion of my fifth philosophical-historical themed adventure in mid to late March.

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, and The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series 2: Autobiographical Writings. 3 volumes. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, and The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series 2: Autobiographical Writings. 3 volumes. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999