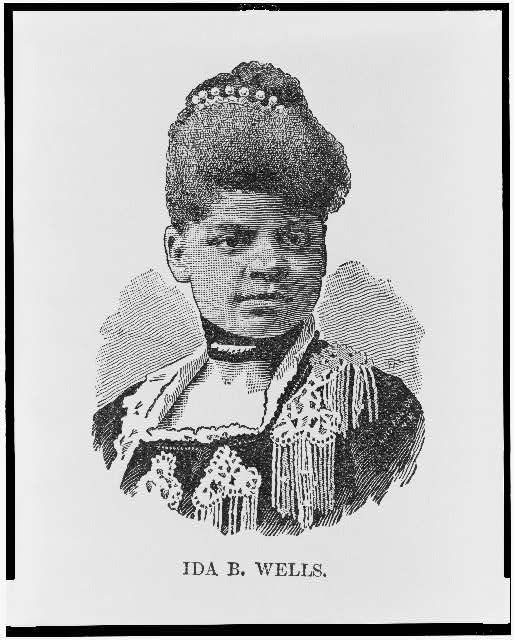

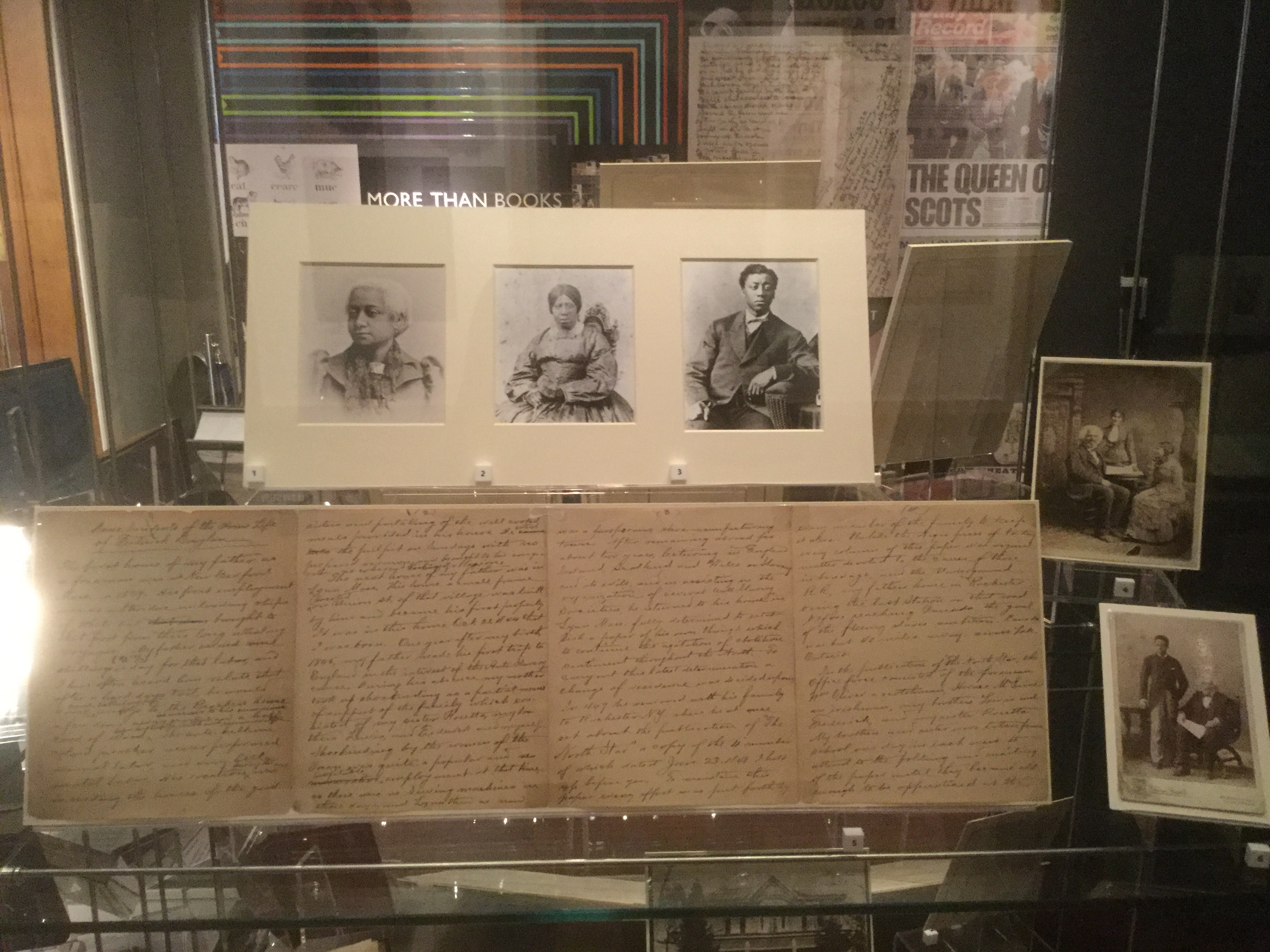

James McCune Smith, closeup of engraving by Patrick H. Reason

On this anniversary of Dr. James McCune Smith’s birth, I’d like to share the story of this great thinker and activist’s life and why I’ve chosen him as the subject of my Ph.D. studies. Rather, in a way, I think he chose me. While researching the life of his colleague, friend, and frequent star at Ordinary Philosophy Frederick Douglass, I came across McCune Smith and was drawn in by his intelligence, passion, writing styles, and fascinating life story. I’m now working on writing the first full-length biography of this great and far-too-little known pioneering African American physician, intellectual, activist, and community benefactor who also made important contributions to history, literature, anthropology, physiology, medicine, constitutional theory, and the emerging field of statistics.

McCune Smith was born in New York on April 18th, 1813, the son of self-emancipated slave Lavinia Smith and, likely, her former master, a merchant named Samuel Smith. From an early age, little James excelled in his studies at New York City’s African Free School No. 2 on Mulberry St. There, he was a classmate of, and over the years, a lifelong friend, colleague, and in some cases biographer of such luminaries as minister and activist Henry Highland Garnet, mathematician and educator Charles L. Reason, engraver Patrick H. Reason, and Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge. All of these, as well as others among their classmates, went on to become leaders in the fight for abolition and equal rights.

Drawing of Napoleon Francois, Charles Joseph, by James McCune Smith, 1825. Published at O.P. with the kind permission of the New-York Historical Society

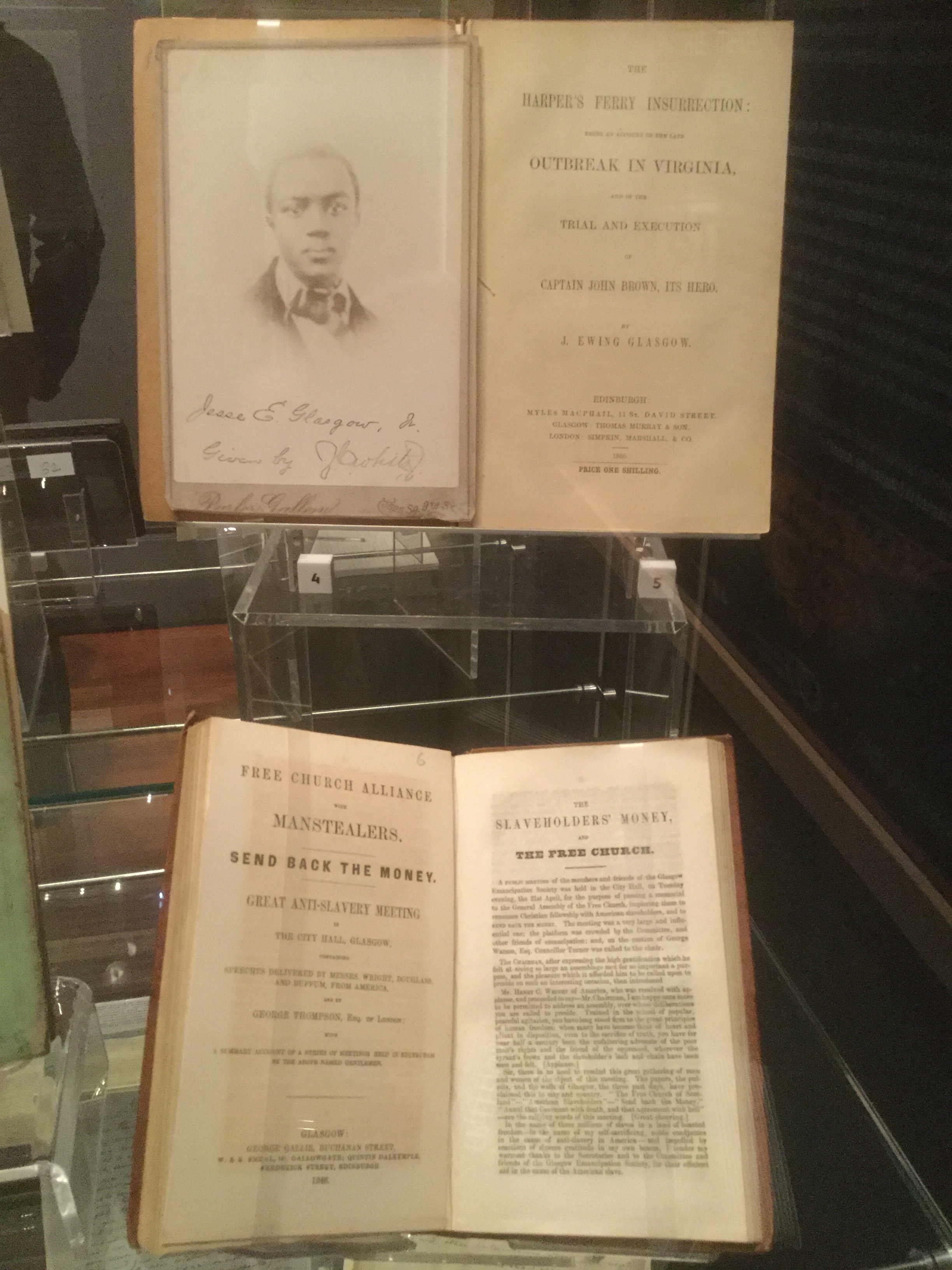

Upon finishing his studies at the Free School, McCune Smith continued his studies independently and with tutors, focusing on Greek, Latin, and the classics; over the years, he would come to be fluent in Greek and Latin, and to gain a working knowledge of French, German, and Hebrew. When his applications for admission were rejected from the medical schools at Columbia and Geneva in New York on account of his African ancestry, McCune Smith applied to the University of Glasgow in Scotland, which had no racial restrictions. He completed his bachelor’s degree there in 1835, his master’s degree in 1836, and his medical degree in 1837, receiving several honors along the way. Upon his return to his native New York City in 1837, he was said to be the most educated African American of his time.

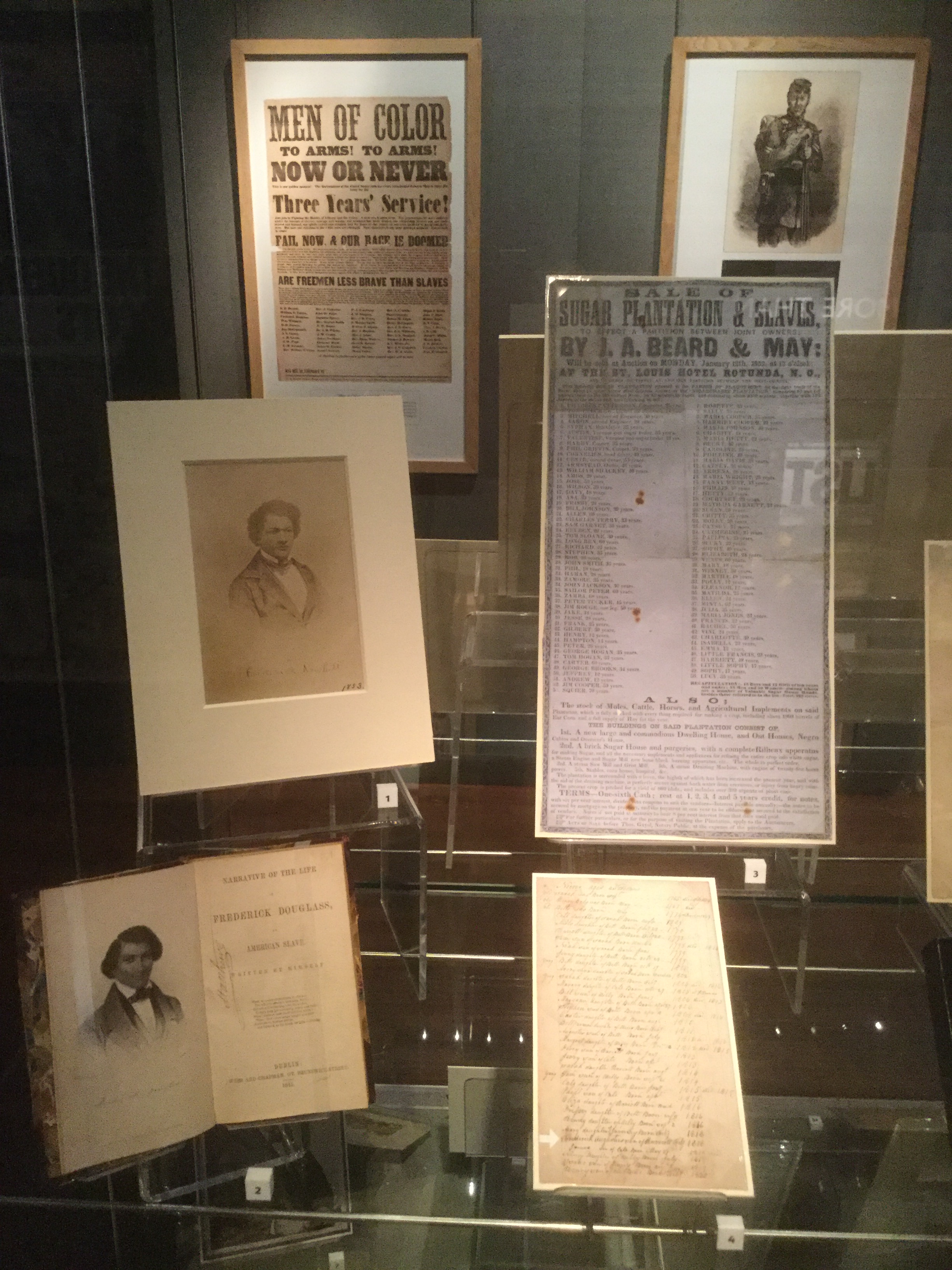

Though he had enjoyed great freedom and opportunity in Scotland, McCune Smith decided to make New York City his permanent home. There, he continued the freedom struggle he had engaged in as a founding member of the Glasgow Abolition Society, this time in his native United States where he felt his efforts were most needed. While he was establishing his pharmacy and medical practice at 93 West Broadway St, McCune Smith also jumped right into political activism, fighting to remove the discriminatory $250 property qualification that applied only to black voters. He is most well known today for his activism in abolitionist societies such as the American Anti-Slavery Society, the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, and the Radical Abolitionists, as well as his leading role in the Colored Convention movement. Yet much, if not most, of McCune Smith’s freedom struggle took place on a personal, community, and grassroots level. He fought for greater economic and educational freedom and opportunity for his fellow New Yorkers of color, regularly gave lectures to raise money for black charities, was a founding member of the Committee of Thirteen dedicated to helping those escaping from slavery, and was the attending physician to the Colored Orphan Asylum for over twenty years.

McCune Smith Cafe & Shop, Glasgow, Scotland, photo January 2019 by Amy Cools

McCune Smith married Malvena Barnet in the early 1840s and together they had (about) 11 children, five of whom survived to adulthood. McCune Smith and Malvena loved raising children and grieved hard over the loss of so many. It must also have been uniquely hard for McCune Smith in his role as a physician administering to children, not being able to save so many of his own from their ultimately fatal illnesses. Yet he managed to keep his hope alive and his energies up, leading an incredibly productive professional, intellectual, and creative life. In addition to his groundbreaking work as the first African American to have a case report presented to a mainstream medical association and to have an article published in a medical journal, McCune Smith wrote prolifically and brilliantly in statistics, several sciences, history, travel, and literature. His writing ranged from concise and clinical to lyrical; from erudite to plain and direct; from sharply critical to experimental; from sarcastic to witty; from righteously angry to tender; from wry to comical.

It was not only suffering the loss of so many children that could have kept McCune Smith down. The Colored Orphan Asylum that he had loved and labored for so long was burned down in New York City’s draft riots of 1863, leading McCune Smith to move his family to the safety of Williamsburg in Brooklyn. He felt frustration, anger, sorrow, and even despair at the intractability of racism and oppression directed at his fellow African Americans despite their abilities, potential, and invaluable contributions to American prosperity and culture. McCune Smith also suffered from bouts of heart disease, lung ailments, and edema for about twenty years, and though he had many health scares over that time, he always seemed to rally and push on. Yet as he wrote occasionally throughout the middle and later years of his life, McCune Smith suspected he would not live a long life. He was right. McCune Smith died of congestive heart failure on November 17th, 1865, at only 52 years old. He had lived to see the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, the end of the Civil War, and the passage of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery, but died just before that Amendment was fully ratified.

Please stay tuned for more about McCune Smith as I continue my research into his life, ideas, and legacy…

Sources and inspiration (not exhaustive by any means, but these are some readily available to share with you online):

‘AFS Bios: James McCune Smith’. Examination Days: The New York African Free School Collection

Associated Press. ‘White Descendants Gather to Honor 1st Black US Doctor, Put Tombstone on His Unmarked NYC Grave’. FoxNews.com, 26 September 2010

Lujan, Heidi L. and Stephen E. DiCarlo. ‘First African-American to Hold a Medical Degree: Brief History of James McCune Smith, Abolitionist, Educator, and Physician.‘ Advances in Physiology Education 43, no. 2 (April 2019): 134-39

Morgan, Thomas M. ‘The Education and Medical Practice of Dr. James McCune Smith (1813-1865), First Black American to Hold a Medical Degree.’ Journal of the National Medical Association 95, no. 7 (July 2003): 603–14

‘Obituary of James McCune Smith’. The Medical Register of the City of New York for the Year Commencing June 1, 1866, 1866, 201–4

Smith, James McCune, and John Stauffer. The Works of James McCune Smith: Black Intellectual and Abolitionist. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006

~ Ordinary Philosophy is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Any support you can offer will be deeply appreciated!