Articles, posters, and mementos of Frederick Douglass scholarship and events, Dr. David Anderson’s office, Nazareth College of Rochester

Tenth day, Tuesday March 29th

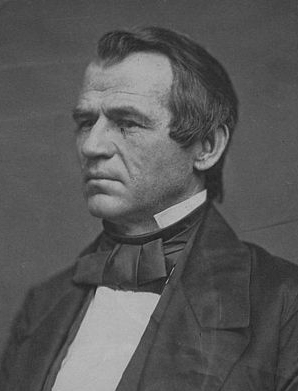

I begin my day with an early visit to Dr. David Anderson, a Frederick Douglass scholar, visiting professor at Nazareth College, founding member of Blackstorytelling League, and an all around delightful and fascinating man! He is kind enough to grant me an interview of an hour or so, which ends up turning into a much longer conversation than that.

Among many other things too numerous to describe in full here (I’ll bring more details of our talk into the discussion of my subsequent discoveries), we talk about the Douglass family as a whole, and especially, Frederick Douglass’ wife Anna.

As discussed in the account of my day in Lynn, Anna took in piecework from Lynn’s thriving shoe industry, attaching uppers to soles, to help support the family. According to Anderson, she brought in enough money doing this to put all of the money which Douglass sent home from his 1845-1847 British Isles tour into the bank. This is but one example of Anna’s hard work and skill as a household manager. The extent of Anna’s contributions to Frederick’ life is often overlooked, Anderson says: if people understood the degree to which Frederick relied on Anna, emotionally as well as logistically, people would understand much more about him too. From the beginning of their relationship, Anna supported his efforts to better himself and to make his escape, selling some of her belongings to fund it and helping him to plan it all out. Anna made the Douglass family home a happy one, and for many stretches especially in Douglass’ earlier years as a traveling speaker, she was often the sole financial support of the family. And when Frederick away on his innumerable meetings and lecture tours, she sent clean clothes ahead to wherever he was traveling, so he was always ready to appear in public neat, tidy, and comfortable.

Anna Douglass circa 1860, image from the Library of Congress collection

Anna did all of this though she could not read or write. As Anderson points out, people often confuse illiteracy with lack of intelligence, and this simple fact, in addition to the general reticence of her personality, has long caused many to write her off as an influential or even very significant figure in Frederick’s life. In fact, she was resourceful, orderly, dignified, creative, and kept their ever-changing and complex life as the family of a traveling speaker and activist together, all while taking care of their constant flow of house guests, including Underground Railroad refugees. As she had been in Lynn, Anna was initially a member of the local Anti-Slavery Society but withdrew at some point. Anderson says it was because of apparent disdain of some of the members for Anna, perhaps because of her lack of education. I ask Anderson if the Society was elitist, but he thinks while this is a possibility on the part of some members, he doesn’t see J. P. Morris, a successful barber and leader of the black contingent of the Rochester Society, this way at all. Presumably, Morris would have set the tone for Society meetings. Whatever or whoever the source of Anna’s discomfiture, she was a dignified person, and it’s easy to see why she would withdraw if she did feel her dignity under attack in any way.

Amy Cools and Frederick Douglass scholar David Anderson in his office at Nazareth College.

For more about Anna Douglass, please listen to my conversation with Leigh Fought, who has made a study of Anna for her upcoming book on the women in Frederick Douglass’ life.

Among the many things I discuss with Anderson, I ask him where Rochester’s City Hall was in 1865; when I had looked for it, I found that the first official one, now called Irving Place / Old City Hall, was built in 1875 at 30 West Broad Street. He thinks it was probably on Broad St because that was the city center, but to make sure I have the exact location, he directs me to the Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County, to the City Historian’s office in the Rundel Building at 115 South Avenue. So that’s where I head next.

Rundel Building, of the Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County, at 115 South Ave

The Rundel building is a handsome structure built spanning the years from the 19-teens through the 1930’s, and its pale gray-brown stone walls are punctuated with inscriptions, including this paraphrase of a John Dewey quote: ‘Education is more than preparation for life, it is life itself’. I’m sure Frederick Douglass would heartily concur, as much as he stressed the practical importance of education as well.

The Rundel building is a handsome structure built spanning the years from the 19-teens through the 1930’s, and its pale gray-brown stone walls are punctuated with inscriptions, including this paraphrase of a John Dewey quote: ‘Education is more than preparation for life, it is life itself’. I’m sure Frederick Douglass would heartily concur, as much as he stressed the practical importance of education as well.

Librarian Cheri Crist, so knowledgeable and so generous with her time, proceeds to help me find what I’m looking for. Not long ago, she made a far more exciting discovery: a previously unknown Frederick Douglass photograph, taken in about 1873 and lost in the depths of the archives for over a hundred years. Today, Crist provides me with sources to help me track down the 1865 location of City Hall, starting with a search of the index card files, though we don’t find any that indicate the right time period there. We decide to cross reference some index entries with old newspapers, and Veronica Shaw helps me find old microfiches of the Rochester Daily Union. (*A clarification from Cheri Crist since this account was published: ‘The resources that we consulted at the Rochester Public Library are from the collection of the Local History & Genealogy Division, which is the department I worked for [as opposed to the City Historian’s office, which is a different entity]’. Thank you for the clarification, Cheri!)

Plat Book of the City of Rochester New York, 1888, Rochester Public Library

Print of old article, Rochester’s Evening Union on sale of Peck Building-City Hall and my notes

Our initial hunt leads us, after many twists and turns among newspaper accounts and old atlases, to an early location of City Hall. I’m all excited about the discovery until a careful rereading of the evidence shows this was in fact Old-Old-Old City Hall, prior to 1856, too early for the historical event I’m following today. Though we first find the wrong place after much searching and end up having to start over again, I find the wild goose chase to be lots of fun: it involves searching through pages and pages of old newspapers facsimiles and city atlases, getting a good glimpse of the history and layout of the city that I wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. I’ve been thoroughly enjoying the level of historical detective work this Douglass journey has led me into all along! We do subsequently find Old-Old City Hall, which, funnily enough, turns out to be much simpler search, it’s just that the right clue doesn’t turn up first: we had started with the index card files rather than old city atlases. More on that soon when I get to the site. In any case, I hope this search leads to a new index card in the City Historian’s files for City Hall between 1856 and 1875.

I realize, as soon as we find the site I seek, that the day’s really getting on, since I spent such a long, absorbing time with Anderson at Nazareth College and Crist at the City Historian’s office. I skeddadle to my next destination, the same place I start my tour of Rochester yesterday. It’s the Susan B. Anthony House at 17 Madison Street.

Susan B Anthony House (left) and Museum (right), at 17 Madison, Rochester

I visit the Susan B. Anthony House today for many reasons. I know Douglass and Anthony were friends (at least sometimes, and of different degrees and kinds when they were). Henry Louis Gates’ timeline in his Douglass Autobiographies compendium and history mentions Douglass visiting her at her Rochester home more than once in 1850, and other sources describe their visits as a regular occurrence around that time. And since they were sometimes friends and always activists in the same causes and lived in the same city for so long, Douglass must have visited Anthony here, right? Well, I find out early in the tour that while Douglass may have visited Anthony at this house and there are many good reasons to think he had, there’s no actual documentation of this. Anthony moved into this house 15 years after that particular 1850 documented visit, and other visits on several occasions while she was living in the family farmhouse now on the outskirts of Rochester, near the airport; more on that in a future account. Douglass lived in Rochester until 1872, and Anthony was among his many friends who pleaded with him to stay. So they must have been on good terms at that time, and she had been living in this house for 7 years by this time. I consider it likely, given all this, he would have visited her here at some point.

Front Parlor of the Susan B Anthony House in Rochester. I snap this photo before I see the ‘no photography’ sign, thinking the policy was the same here as in the museum. But the deed is done, and I’m not one to let a perfectly good photo go to waste

Parlor of Susan B. Anthony House as it looked in her time, this is my photo of the photo at the museum exhibit

Susan B Anthony House Museum plaque telling the story of her arrest for voting in 1872, and a brief timeline of her life

I have a most delightful visit, in a quiet moment between tours, with Linda Lopata, the Visitor Center manager, and Carolyn, Mary, and another kind woman whose name I can’t recall at the moment; if you read this, please excuse my forgetfulness, and I would be delighted to be reintroduced! They have a wealth of information to share and couldn’t be more kind, and are so sweet in their interest in my project and willingness to help. We talk some about Douglass, about whom they’re quite knowledgeable, and a lot about Anthony, including her arrest at this house for voting in the 1872 presidential election along with fourteen other women. Try as I might in an hour-plus-long search, I can’t find their names listed anywhere. It bothers me somehow to leave them anonymous, as all the sources I’ve found so far do, when they acted as bravely and with as much conviction at the polls as Anthony did! (I would be grateful, dear reader, if you happen to know how where to find their names and can pass the word along. Unless, of course, these women desired their names to remain anonymous, as was their right, to avoid scandal or censure. UPDATE: the always delightful and helpful Paige Sloan sent me a link to a page where the names of these brave voters are listed: their names are Charlotte Bowles Anthony, Mary S. Anthony, Ellen S. Baker, Nancy M. Chapman, Hannah M. Chatfield, Jane M. Cogswell, Rhoda DeGarmo, Mary S. Hebard, Susan M. Hough, Margaret Garrigues Leyden, Guelma Anthony McLean, Hannah Anthony Mosher, Mary E. Pulver, and Sarah Cole Truesdale.) The officials who allowed them to register to vote likely sympathized with their cause, and were certainly convinced by her interpretation of the 14th and 15th Amendments, that the first strongly, and the latter less so, implied that women had the right to vote.

Douglass, the ardent feminist and advocate of universal suffrage, must certainly have approved of this bold move, and the fact that all save one voted for his preferred candidate Ulysses S. Grant would have pleased his too. But he was no longer in town to lend his support in person, since he and his family had already moved to Washington D.C. that July.

Monroe County Executive Office building at S. Main and Fitzhugh Streets. The north of the building, where Patrick Printing is now, covers the site of Rochester’s City Hall in 1865. Pindle Alley runs through that little space you can see between the MCEO building and the Powers Building next door

My next destination is less than a mile almost directly east, at S Fitzhugh St just a little south of Main, to the site of the City Hall in 1865 we had searched for so assiduously this morning. The digitized 1863 map we found on the Monroe County Library System’s website shows that it stood where the Monroe County Executive Offices stand at 39 West Main is now. The long red brick building’s north end covers the site. As you can see from the ‘Reference’ (legend) at the top right of the map, #55 identifies that City Hall location, just across the street from that Old-Old-Old City Hall site we discovered at the corner of Main and tiny Pindle Alley, and just a little north from the Irving Place Old City Hall built in 1875, all three within a two-block radius.

Abraham Lincoln with his son and 2 views of his tomb, photos from the Hutchinson family scrapbook at the Lynn Museum

I seek this site today because Douglass gave an impassioned, impromptu eulogy here in remembrance of his hero and friend Abraham Lincoln. A crowd had gathered here on April 15th, 1865 to mourn Lincoln’s death that morning, and they called upon Douglass to speak. He did so, delivering by all accounts one of the most moving addresses he ever gave. As Douglass sadly told them, ‘It was only a few weeks ago that I shook his brave, honest hand, and looked into his gentle eye and heard his kindly voice.’ That occasion was on March 4th of that same year, when Douglass went to the White House to congratulate Lincoln on his second inauguration and the excellence of his address. A you may remember, Douglass was critical of Lincoln’s first inaugural address, with its weak stance on slavery. The second, besides its sheer eloquence and beauty, was unapologetically anti-slavery, so of course Douglass heartily approved of it. Douglass went to the White House on his own account and was turned away at the door by two officers who said they were instructed by Lincoln not to admit black people. Douglass accused them of lying, which they were, and insisted on entering. He was ultimately successful, and when Lincoln spotted Douglass across the room, he called out ‘Here comes my friend Douglass’ and shook his hand. This was a moment of great triumph and validation for the proud, dignified Douglass, and he would treasure it for the rest of his life.

Downtown United Presbyterian Church and adjoining hall with 1848 Rochester Women’s Rights Convention commemorative plaque.

1848 Rochester Women’s Rights Convention plaque at the Downtown United Presbyterian Church.

My next destination is just two long blocks north, Downtown Presbyterian Church at 121 Fitzhugh St. It’s a lovely building with beautiful stained glass windows. It takes many, many attempts to snap any photos I can use since the sun is sinking low right behind the church, and still, I can’t quite color-correct the photos enough to do it justice. In the process, three ladies on separate occasions stop to exclaim something to the effect of ‘isn’t it beautiful?’ and to invite me an event going on there that evening. On an adjoining building to the left of the church, there’s a plaque commemorating the 1848 Rochester continuation of the Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention, which we’ll discuss in my next day’s account of this journey. This used to be the Unitarian Church, and the meeting was held in the church building itself. Douglass spoke at this convention as well, according to Ms. Lopata at the Susan B. Anthony House. In his remarks, he reiterated his conviction that he could not deny a woman any right he claimed for himself, nor could any just individual do so.

American Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in the historic Corn Hill neighborhood of Rochester. The Douglass family were members of this congregation who worshiped in one of the church’s earlier incarnations nearby, no longer standing

Site of apartment building on Clarissa at Greig St where the great Son House once lived.

I zigzag my way a little over half mile east to the historic Corn Hill District, where the Memorial African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church now stands at Favor and Clarissa Streets, just off Ford. According to Cindy Boyer, Rochester’s Landmark Society director of public programs, ‘Clarissa Street was once the business and cultural heart of Rochester’s African American community… In the 1950’s, it became a jazz and entertainment hub.’ Exploring Clarissa St on my way from the current location of the AME Zion Church at 549 Clarissa St to the old site, I notice one of those distinctive blue historical marker signs and discover that the great bluesman Son House lived on Clarissa at Grieg St in the 1960’s. Cool.

The original site of the AME church was just a little east of this one, on the northeast corner where Spring and Favor streets once intersected, near where the 490 freeway now passes through. Anderson directs me here in our discussion this morning, as the Douglass family belonged to this progressive congregation, dedicated to reform and the education of black children. The church was also an important stop on the Underground Railroad. It had been reorganized and rebuilt by Thomas James, a former slave who became a minister and educator who founded new congregations in several cities. James was the one, according to Anderson, who had licensed Douglass, many years ago, to preach in New Bedford.

According to Michelle Finn, Deputy Historian of the City of Rochester, ‘The third church building, which is depicted in this photograph, featured memorial windows dedicated to Douglass, Anthony, Harriet Tubman and others’. I wonder why ‘featured’ is in the past tense: the photos reveal it’s the same building that stands today, and it appears there’s stained glass within the outer panes I can see from where I’m standing. Perhaps the stained glass windows are no longer intact; the church is all closed up, padlocked and surrounded by chain link fence so I can’t approach it to make sure.

I continue on, crossing over the Frederick Douglass-Susan B. Anthony Memorial Bridge, which carries Interstate 490 over the Genesee River in downtown Rochester, to my next destination.

Rosetta Douglass home at 271 Hamilton Street at Bond

Another view of Rosetta Douglass home at 271 Hamilton Street

At 271 Hamilton Street at Bond, there’s a two story blue house which was not long ago discovered to be a home owned by Douglass and his daughter’s family. This makes it the first house that Douglass owned and stayed in for any length of time that’s still standing, so I’m very excited to discover it too! Anderson’s colleague and fellow historian Jean Czerkas made the discovery of the deed for the house that had Douglass’ name on it. ‘She’s serious!’ said Anderson to me this morning. Czerkas has made many other important discoveries in local history over the years, including sites associated with the life and work of Austin Steward, one of Douglass’s fellow black abolitionists and Underground Railroad operatives and a successful Rochester business owner. ‘[Czerkas] helped me in another way’ Anderson continued. ‘She found out Austin Steward had children buried in Rochester.’ Steward is a fascinating figure, I’m very glad to learn about him and encourage you to so as well; like Douglass, he wrote a narrative of his life first as a slave, then as a free man and anti-slavery activist.

Douglass’ daughter Rosetta and her husband Nathan Sprague lived in this house for several years before following her father to Washington D.C. Douglass kept the house, however, listing himself as a boarder. Since he had fought so long for the right to vote and residents of Washington D.C. could not vote in presidential elections at the time, he retained that precious right for himself by keeping an official residence in Rochester.

James P. Duffy School, which stands on the site of the Douglass family home and farm, then on the outskirts of Rochester, on South Avenue. The school is being remodeled and improved.

Fredrick Douglass Community Library adjacent to the Duffy school, original site of the Douglasses’ South Ave home

I head south on Alexander St and turn left on South Avenue, which continues to take me south toward Highland Park. I look for the historical marker which I read is located at the site now occupied by James P. Duffy School at 999 South Ave near Highland Park, and for the community library now named after Douglass. Anderson said he and other local historians and citizens are making good headway in getting the school renamed after Douglass too. I easily find the school, which is being rebuilt. But I find no historical marker, though I circle the building slowly and scan the area carefully. Perhaps it’s been taken down until the construction is done, or it’s obscured by the large quantity of construction equipment and materials here now. (Update: fellow Douglass enthusiast and Rochester resident Paige Sloan comes to the rescue again and does a little more searching, locating the historical marker at this site. See the photos below.)

Frederick Douglass South Ave home site near the school under construction, with the historical marker now visible from this angle just beyond the red sign since it’s now leaning to the left. Photo 2016 by Paige Sloan

Frederick Douglass South Ave home site marker, 2016 Paige Sloan

In 1852, Frederick Douglass moved his family here from that urban red brick house on Alexander Street to a hill top farmhouse on what was then the outskirts of the city. It was private, with no near neighbors, plenty of land surrounding it, and fruit trees galore: a perfect setting for five growing children and for sheltering runaway slaves. Both Douglass family homes in Rochester were Underground Railroad institutions.

Douglass loved his South Ave home and farm. He built a cozy office and library upstairs, he loved to ride his large white horse on the grounds, he planted trees with his own hands, his sons worked the land, and Anna kept a beautiful and orderly home. They lived here for twenty years, until June 2 1872, when it burned to the ground. The family escaped unharmed, and friends helped the family save many of their personal goods and all of the animals, but many of Douglass’ important papers and bound volumes of every issue of the North Star were burned. We suffer their loss too, as copies of very many have never been found elsewhere. Douglass was of town the day the house burned, and returned the next day having heard the news. He believed the fire was purposely set; the fire insurance company agreed with him. He had continued to struggle with elements of racism even in this relatively tolerant city, the city he said he felt most at home in, enough to believe the worst. He was so bitter over it that he decided to move his family to Washington D.C. for good. Their daughter Annie had died here in 1860 at only 10 years old; perhaps Anna’s unabated grief made her more amenable to moving from the place they had called home for twenty five years.

Frederick Douglass Memorial Square at Highland Park, at South Ave and Robinson Drive. You can just make out Frederick Douglass’ monument / statue in the background just to the right of the signpost.

Then I continue up the hill, just a short stroll continuing south on South Ave to Robinson Dr, to end my day’s explorations at beautiful Highland Park. It was designed in 1890 by another Frederick, Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Manhattan’s Central Park and Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. Olmsted is famous for creating some of the world’s most beautiful parks, with landscapes designed to look as natural as possible while maximizing their utility as public spaces.

Frederick Douglass Monument and Statue in Highland Park, Rochester NY. It’s the first monument erected to memorialize an African American in the United States.

I cross Robinson Dr. to my right at an angle, then into the park down to Highland Bowl, the natural amphitheatre between Robinson Dr and Reservoir Ave with an Art Deco look open air theater built at its west end. Across the large grassy depression that makes the bowl, halfway up the hill on the other side from Robinson and to the left (or east) of the theater, there stands an 8 foot statue of Frederick Douglass on a tall columnar pedestal, with four plaques curved around it, three containing Douglass quotes. First erected in front of Rochester’s New York Central Train Station in 1899, it was moved to Highland Park in 1941, to place it in a more beautiful, dignified natural setting instead of the dust and bustle of the street corner it had been on. It’s also fitting that it’s placed near the site of his beloved South Ave home.

I cross Robinson Dr. to my right at an angle, then into the park down to Highland Bowl, the natural amphitheatre between Robinson Dr and Reservoir Ave with an Art Deco look open air theater built at its west end. Across the large grassy depression that makes the bowl, halfway up the hill on the other side from Robinson and to the left (or east) of the theater, there stands an 8 foot statue of Frederick Douglass on a tall columnar pedestal, with four plaques curved around it, three containing Douglass quotes. First erected in front of Rochester’s New York Central Train Station in 1899, it was moved to Highland Park in 1941, to place it in a more beautiful, dignified natural setting instead of the dust and bustle of the street corner it had been on. It’s also fitting that it’s placed near the site of his beloved South Ave home.

As you can see from the photos (though I’ve brightened them quite a bit so you can see the details), it’s growing late: dusk is drawing near. It’s been a long and fascinating day, I learned so much it will take some time to process it all, and I’m tired. The park is soft and lovely this evening, the trees bare and gray and lacy with their delicate veiny branches, the grass beetle green in the lowering light. I gaze at the statue awhile and reflect, then I sit in the grass and rest, lazily typing up a few notes. I like the way the statue’s hands are outstretched, palms up, as if Douglass is inviting you to draw near and hear what he has to say. So I’ll let him close this day account’s with his own words, until we meet again in the story of the next day of my Douglass journey:

Frederick Douglass quotes on his monument pedestal. There are many more powerful, original, and memorable Douglass quotes than these ones here that I wish they’d included instead. But these were chosen for popularity’s sake no doubt, as they express godly and patriotic sentiments

*Listen to the podcast version here or on Google Play, or subscribe on iTunes

~ With special thanks again to Paige Sloan, who heads and teaches a writing program for international students at the University of Rochester and, like me, is a big Fredrick Douglass fan! She provided me with an additional source for my Corinthian Hall research and a photo I neglected to take for my account of my first day in Rochester, and a link to a list of the women who voted with Susan B. Anthony for this day’s account.

~ Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and Inspiration:

‘28. Frederick Douglass Rural Homesite‘. The Freethought Trail website

‘Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass‘. Lehrman Institute: Abraham Lincoln’s Classroom

‘Austin Steward, 1794-1860‘. From The Back Abolitionist Papers: Vol. II: Canada, 1830-1865 ed. by C. Peter Ripley, et al, 1992 by the University of North Carolina Press, via Documenting the American South

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, and The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series 2: Autobiographical Writings. 3 volumes. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999

Cornell, Silas. Map of the City of Rochester, 1863, Rochester Images, Monroe County Library System website

Douglass, Frederick. Autobiographies (includes Narrative…, My Freedom and my Bondage, and Life and Times). With notes by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Volume compilation by Literary Classics of the United States. New York: Penguin Books, 1994.

‘Dr. David A. Anderson/Sankofa‘, Blackstorytelling League of Rochester

Finn, Michelle. ‘The Memorial African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church‘. Democrat & Chronicle: Retrofitting Rochester series

Foner, Philip S. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. 1-4. New York: International Publishers, 1950.

Highland Park Conservancy: ‘History of the Park‘ and ‘Park Map and Audio Tour‘

History & Political Science Directory: David Anderson. Nazareth College website.

History of the Federal Judiciary: The Trial of Susan B. Anthony- Biographies-Other indicted voters. From the Federal Judicial System website

‘Irving Place‘. In RocWiki, The People’s Guide to Rochester.

Linder, Doug. The Trial of Susan B. Anthony for Illegal Voting, 2001

McKelvey, Blake. ‘Lights and Shadows in Local Negro History‘. Rochester History, Vol 21, No. 4, 1959

Meives, Caitlin. ‘Recognition For a Forgotten Frederick Douglass Site‘. Landmark Society of Western New York website.

Memmott, Jim. Don’t Ignore Douglass Statue. Democrat & Chronicle, July 1, 2015

Morry, Emily. ‘Frederick Douglass Home on Alexander Street’. Democrat & Chronicle: Retrofitting Rochester series

Morry, Emily. ‘Frederick Douglass Monument’. Democrat & Chronicle: Retrofitting Rochester series

‘Rediscovering Frederick Douglass‘. City of Rochester website

‘Rundel Memorial Library Building‘. In RocWiki, The People’s Guide to Rochester.

Schmitt, Victoria Sandwick. ‘Rochester’s Frederick Douglass Part One‘ and ‘Rochester’s Frederick Douglass Part Two‘. Rochester History journal, Vol. LXVII Summer 2005 No. 3 and Vol. LXVII Fall 2005 No. 4. McFeely, William. Frederick Douglass. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991.

Steward, Austin. Twenty-two Years a Slave, and Forty Years a Freeman. Rochester, 1857.

Susan B. Anthony Home & Museum website, all articles linked to on Her Story page

University of Rochester Library Bulletin: Report of the Woman’s Rights Convention, 1848, Volume IV · Autumn 1948 · Number 1. University of Rochester River Campus Library website

Wemett, Laurel. ‘Austin Steward: A Forgotten Figure in Abolitionist Movement‘. Canandaiga Daily Messenger, Feb. 4, 2013.

I’m pleased and honored to present my third interview guest, Leigh Fought, Anna and Frederick Douglass scholar and assistant professor at LeMoyne College in Syracuse. We’ll be talking about Anna Douglass, about whom I believe too little is known, and most historical presentations of her range from woefully incomplete to inaccurate and even unfair. Ms. Fought is doing significant work in righting this with her upcoming book about the women in the life of Frederick Douglass, the most significant of which, of course, is Anna.

I’m pleased and honored to present my third interview guest, Leigh Fought, Anna and Frederick Douglass scholar and assistant professor at LeMoyne College in Syracuse. We’ll be talking about Anna Douglass, about whom I believe too little is known, and most historical presentations of her range from woefully incomplete to inaccurate and even unfair. Ms. Fought is doing significant work in righting this with her upcoming book about the women in the life of Frederick Douglass, the most significant of which, of course, is Anna.