A page from Ernest East’s Abraham Lincoln Sees Peoria, published in 1939, in the collection of the Local History Room, Peoria Public Library

Peoria, Illinois, July 28th, 2017, continued

From the 200 block of N Jefferson Ave between Hamilton Blvd and Fayette St, I zigzag my way south past Courtyard Square. According to Lewis Lehrman’s Lincoln at Peoria: The Turning Point, ‘Douglas and Lincoln probably stayed at Peoria House… at the corner of Adams and Hamilton Streets.’ Peoria House was a popular place for visitors to stay until it was destroyed by fire in 1896. According to Peoria Historical Society, it was replaced in 1908 by the grand Hotel Mayer, which, in turn, would burn down in 1963, when a drunken guest’s bedding caught fire and spread. The site is now occupied by a large Caterpillar office building.

Ernest East, however, writes in his Abraham Lincoln Sees Peoria that Lincoln definitely was a regular guest here. A contemporary newspaper report about one of these occasions, on March 27th, 1857, said ‘Hon. Abraham Lincoln is in our city and stopped at Peoria House. Mr L., it will be borne in mind, is to be our next United States Senator. The people have decreed it–the next legislature will have only to ratify their nomination.’ The Peoria Republican proved overconfident, however. Though the Republicans won the popular vote, senators were then elected by the legislature, and due to some last minute political wrangling, Lincoln’s political sparring partner Stephen A. Douglas was awarded the office instead.

Mayer Hotel, 1907 to 1963, built at old Peoria House site at Adams and Hamilton, Peoria, Illinois

Lincoln had served one term in Congress, from 1848-1849. This was his highest office before being elected as President in 1860, which was almost twelve years later. As with my musings on my visit to Galesburg, Barack Obama comes to mind often when I think of the historical and political issues connected to Lincoln. After all, Obama’s presidency is, in some part, Lincoln’s legacy too. Obama was also elected President after serving as United States Senator, in his case serving seven years in Congress, as opposed to Lincoln’s less than two-year service with a several year gap between. Nevertheless, I remember many people complaining that Obama was unqualified, with far too little political experience. I don’t remember ever hearing this about Lincoln, though I’m certain this was a big issue for many voters at the time. Lincoln did, however, have a good deal of experience in the state legislature, and like Obama after him, was very experienced in the law. The proof’s in the pudding, I suppose, and the leadership abilities that Lincoln demonstrated throughout his Presidency had made us forget, so many years later, that he was not a seasoned statesman when he entered that office. We have yet to see how Obama’s legacy will fare with the test of time beyond the historical importance of the fact that an African-American was elected to two terms as President. I believe it will hold up fairly well, despite the unremitting and I think, unpardonably nasty opposition to every single one of his policy objectives while he was in office. And Obama’s grace and dignity under fire are beyond reproach, in my view. He certainly kept to the moral high ground.

Presidents Barack Obama and Abraham Lincoln

Many readers might object to my characterization of Obama’s presidency as in any way a part of Lincoln’s legacy. After all, wasn’t Lincoln a racist and only a reluctant abolitionist? I reply, yes, both of those things are true, but the story is much more complicated. It’s also true that Lincoln evolved over time, in his heart as well as in his mind, and the evidence shows he came to believe that abolition was not only politically the best thing to do, but also the only morally right thing to do. Remember that Frederick Douglass met him, personally, on multiple occasions when Lincoln was President, and he came away from each of those meetings convinced that Lincoln was personally free from racial prejudice. Douglass was not a man to be fooled: he was a longtime and fierce critic of Lincoln’s, both before and after these meetings.

And remember too, that for all his imperfections, Lincoln was the lead man in actually getting that crucial, terribly stressful job of legally abolishing slavery done, facing down the vehement opposition at great cost to his own physical and mental health. Obama also went through this sort of political and moral transformation. He had initially opposed legal marriage equality for gay couples based primarily on his own religious beliefs. Nevertheless, what he learned in the process of leading this diverse nation of free people was sufficient to change his mind. Obama eventually offered his strong public support for the right of gay people to marry. He also nominated progressive justices to the Supreme Court who were more likely to consider marriage equality cases as matters of equal protection rather than matters of tradition. Which they did in 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges decision, which effectively legalized gay marriage, based on the grounds that denying it to gay couples violated 14th Amendment guarantees of due process and equal protection. I hope that one day I’ll write about the first United States Presidency of a gay person being, in part, Obama’s legacy as well.

Caterpillar AB building at Adams and Hamilton, on the site of the old Peoria House and then the old Meyer Hotel in turn, opposite Courthouse Square in Peoria, Illinois. Abraham Lincoln stayed here many times, and Stephen A. Douglas may have stayed here as well.

Next, I seek the site of a building that stood near the old Mayer Hotel site a century after Lincoln stayed there. Robert G. Ingersoll first moved here to Peoria in 1857 as a young lawyer with his brother Ebon Clark Ingersoll, also a lawyer, who eventually became a congressman. They opened a law office at 4 Adams St ‘opposite the courthouse, on the second floor of a two-story frame house reached by an exterior staircase,’ according to his biographer Edward Garstin Smith. Today, the section of Adams St that’s across from Courthouse Square is entirely occupied by that huge Caterpillar office building, pictured above, that also covers the old Meyer Hotel site.

According to local historian Norman Kelly, the young Bob Ingersoll and about ten of his friends got themselves arrested in September of 1857, that first year he lived here. They had set a bonfire in the middle of Main Street, singing songs around it at two in the morning. Perhaps Ingersoll was just a little too excited about his new home! In any case, after they had sobered up, Ingersoll requested a trial where he would represent the whole bunch of carousers, including himself. He conquered the jury’s hearts and minds with his combination of impressive legal knowledge and droll humor, promising that he and his buddies would perform a rousing rendition of that same song for them if the jury would acquit… with the understanding that the acquittal would be in accordance with the evidence and the law, of course. An acquittal did follow, but the account doesn’t reveal whether the jury got their concert. I like to imagine they did.

According to a letter to his brother John in February of 1858, Ingersoll slept at the law offices and boarded at ‘the finest hotel in the city;’ Ebon and his wife lived elsewhere. So, for the most part, that law office on Adams Street was Ingersoll’s first home in Peoria.

Caterpillar welcome center, at the southeast corner of Main and Washington, on the site of the Ingersoll law office from 1873-1875

I walk one block south and west and stop at the southeast corner of Main and Washington Streets, where Ingersoll moved his law practice in 1873, three years after his tenure as Attorney General of Illinois and before he moved his solo practice to his home in 1876. His office was on the second floor of the Second National Bank building, which became the Peoria National Bank. Ingersoll had spent the intervening years making a living on the lecture circuit, in which he was very successful, and campaigning for Republican candidates for office.

The Clinton House was built in 1837 as a two-story brick hotel at Adams and Fulton Streets. It was destroyed by fire in 1853, and Schipper and Block department store was built on the site in about 1879. The name was changed to Block & Kuhl in 1914. Local History and Genealogy Collection, Peoria Public Library, Peoria, Illinois

Adams and Fulton Sts detail, Insurance Maps of Peoria, Sanborn 1927, Local History and Geneology Room, Peoria Public Library

I double back on Main one block north, then head left on SW Adams another block. The old Clinton House used to stand at Fulton and Adams Streets. The conversation I had with Chris Farris at the Local History and Geneology Department earlier today led me to the white terra cotta glazed two-story department store building that used to be Newberry’s. Therefore, I take photos of that location. However, the more I dig, the more I discover that can’t be the site. A closer reading of the Abraham Lincoln Sees Peoria account of Lincoln’s visit to the Clinton House, and double-checking the 1927 Sanborn map against postcards of the Clinton House and the Block & Kuhl Department Store that was built on the site, reveal that the Block & Kuhl department store, and thus the Clinton House, stood on the other side of the street. The old Chase Bank Building stands there now.

Former Chase Bank Building which stands at the former site of Clinton House and then the Block & Kuhl department store, photo by Dave Zalaznik, use courtesy of Peoria Journal Star

Aerial view of Adams and Fulton with the ‘The Big White Store’ Block & Kuhl, once Schipper & Block, now the site of the old Chase Bank Building and once the site of the old Clinton House, Peoria IL, Local History & Geneology Collection, Peoria Public Library

Selection from the Peoria Register and North-Western Gazetteer, February 15, 1840, p 3, Library of Congress

More digging for details of the Clinton House and Lincoln’s visit here uncovers a newspaper announcement of the re-opening of Clinton Hall to the public under John King’s management. The Peoria Register and North-Western Gazetteer published this on February 15th, 1840, but the announcement includes an earlier date: November 16, 1839. Therefore, King had already been running the house for nearly 3 months when Lincoln and 120 other men dined here on February 10, 1840. The dinner followed a rally for Whig presidential candidate William Henry Harrison on February 10th, 1840, at which Lincoln spoke.

Lincoln was a committed Whig before he joined the Republican Party, which was formed 14 years after the Harrison rally. As a Whig, he supported protectionist policies such as high tariffs on imported goods, intended to boost American wages and industry. Today, this sort of policy is more likely to be found on the Democratic side of the political aisle, but not always. Bernie Sanders’ platform, in his bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, included many protectionist policies, but our current Republican president Donal Trump has also advocated slapping high taxes on imports. I wonder what Lincoln would think now, given the additional economic evidence from the past 150-plus years. I don’t believe, myself, that protectionism helps labor in the long run, neither here nor abroad: it blocks access to goods that people need and want and keeps too many out of the workforce. Such tariffs are based on the idea that the marketplace is a zero-sum game, like trying to make and share a pie when only one size tin is available. In reality, however, the more people who can and do participate in making the pie, there’s no market-imposed limits to the size. (There are ecological limits, but that’s another story.) It takes regulation, not tariffs, to ensure that a few greedy gobblers don’t keep others from enjoying the bounty too.

Robert Ingersoll as a Civil War commander, early 1860’s

I pass through the Fulton Street Plaza, where the street narrows to form a walking path through a small park between Adams St and Jefferson Ave, and head back along Main St.

There are three addresses on Main Street that I seek, but the given addresses don’t match the old atlases I have access to, nor are there specified landmarks except a mention of proximity to the Courthouse: 1) In 1861, Robert and Ebon Ingersoll moved their law office from the one they had opened at 4 Adams St in 1857 to 55 Main St, 2) In 1865, now a married man, a Civil War veteran, and a father of two, Ingersoll’s office moved again to 45 Main St when city attorney S.D. Puterbaugh joined the practice; Ebon had left in 1864 to enter Congress, where he would serve for 7 years, and 3) in 1868, Ingersoll moved the office to 46 Main St when he took on another law partner, Eugene McCune, the city prosecutor. I don’t have a story right now in connection with these particular locations, but I may as well share these facts since I’ve obtained them, in case they may be useful to another doing historical research.

Civic Center from N William Kumpf Blvd, near site of old AME Episcopal Church, Peoria, Illinois

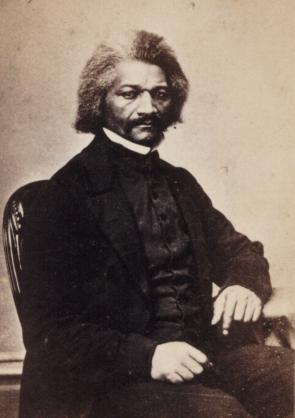

Frederick Douglass, ca. 1870 (Gilder Lehrman Collection)

I make my way next to a site that used to be at Fifth and Monson, but both those streets have disappeared under the vast pavement of the Peoria Civic Center on N William Kumpf Blvd. Somewhere under all this asphalt and the sprawling concrete sports and events edifice used to stand the Ward Chapel African Methodist Church. Douglass spoke here in Peoria for the last time on February 7th, 1870 to this congregation and their guests. The address he delivered on that occasion is titled ‘Our Composite Nationality.’ The membership of all races in one great human family was among Douglass’ favorite themes, and this conviction drove Douglass’ work as a champion for many human rights causes: for the rights of Chinese and other foreign-born immigrants and citizens; for universal suffrage; for freedom of thought and religion; for improved conditions and wages for laboring people; for providing education to the disadvantaged; for just treatment of Native Americans; for prosecuting lynchers; and for many, many more.

On this day Douglass said,

‘I am told there is objection to this mixing of races. We do not know what the original race was. It does not matter whether there was one Adam, a dozen Adams or 500 Adams. ‘A man’s a man for a’ that.’ [I love this inclusion of a line of Scottish poetry. I’m planning a series about Douglass here in Scotland while I’m living here for the next year.] I begin with manhood. Smiles and tears have no nationality. My two eyes tell me I have a right to see, my two hands, that I have a right to work. Almond eyes are not solely peculiar to the Chinaman. Hues of skin not confined to one race… I close, as I began, in hopes for the republic. Let us rejoice in a common sympathy and a common nationality supporting each other in peace and war, and to the security of a common country.’

Hear, hear, Mr. Douglass. We could really use you here today. Many carry on your fight for social justice but few with your power, eloquence, and wisdom. (And handsome face.)

Facing the northeast corner of Globe and Hamilton, former site of the Tabernacle, Peoria

The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, July 24, 1899, out of W. Virginia, from Chronicling America, Library of Congress

My last stop of the day is half a mile north on my way back to my hotel room, so I pick up the car from where it’s parked near the Peoria Public Library, and drive uphill towards the big OSF Saint Francis Medical Center. When I arrive, I find a brand new parking lot and medical building at the northeast corner of Hamilton Blvd and Globe St, the UnityPoint Health Methodist Ambulatory Surgery building. It’s so new that Google Maps still shows nothing at the site but freshly leveled dirt and huge pipes ready to go into the ground.

This was the site of the Tabernacle, a huge octagonal multi-purpose structure built in 1894. A memorial service was held here for Ingersoll on July 24th, 1899 three days after his death. He was not buried in Peoria; he had moved to Washington D.C. in 1878, once again opening a law office with his brother, and then moved back to his native state of New York in 1885. His ashes were interred in Arlington National Cemetary since he was a Civil War veteran. But Ingersoll was among Peoria’s most famous and treasured adopted sons, having lived here for a little over 20 years. So, it was wise to hold his memorial service in such a large space.

Looking back at Peoria’s downtown skyline from this rise, I’m treated to a lovely view. What a nice location for the city to pay tribute to one of its beloved former citizens.

View of downtown Peoria from near the former site of the Tabernacle at Hamilton and Globe

One more thing: Lincoln spoke briefly but memorably once at the Main St Presbyterian Church in the summer of 1844. I dig and dig but have the hardest time locating the site of that church. There was a very tiny congregation of Presbyterians co-founded by Lincoln’s good friends Lucy and Moses Pettengill in 1834 who, by the way, ran an important stop on the Underground Railroad from their home on Liberty and Jefferson. This Presbyterian congregation split into two: New School and Old School. Each one moved and changed named multiple times, especially the second one, so I don’t ever succeed in obtaining a photo of the 1844 New School Main Street church which Lincoln spoke at. But I do find a description of the location in East’s biography: the church was ‘situated on the lot above the alley adjoining the present Alliance Life Company building.’ The then-present Alliance Life Company building is the now-present Commerce Bank building, which is my second stop of the afternoon in search of the site of Rouse’s Hall where Frederick Douglass spoke on at least three occasions. I find no map which shows the location of that old alley, but it’s somewhere near where that long low 1960’s concrete building is in the photo above.

Commerce Bank, once the Alliance Life Company Building, Peoria, Illinois

Lincoln’s speaking appearance was an impromptu one this time: he was in town for a court appearance when he was persuaded to debate Colonel William May. May was a lawyer and former Congressman who started out as a fellow Whig, switched to run for Congress as a Democrat, switched back again to support Whig William Henry Harrison, and was a Democrat again by the time Lincoln accepted this debate. Why Lincoln did so, I don’t know. The terms of the debate were so circumscribed, including a ban on discussing May’s political career, that it doesn’t sound like an enticing opportunity to me, given the plentiful fodder that May’s checkered history would provide for a vigorous and entertaining exchange.

Apparently, Lincoln thought so too. May, who was also a respected debater, used the latter portion of his time to rip apart the Whig party, comparing it to a liberty pole that looked nice from the outside but had actually been weakly spliced together from disparate elements, with dry rot leaving a gaping hole in the center. After May had left that door wide open for him, Lincoln couldn’t help but walk through it. He stood up and responded ‘Why, Colonel, that is the hole you left when you crawled out of the Whig party.’ After Lincoln followed with the suggestion that the hole be filled up so May couldn’t crawl back in, the crowd started laughing and arguing, the Whigs delighted, the Democrats angry that Lincoln had violated the terms of the debate. He acknowledged the latter and apologized, I think insincerely since he remarked that the opportunity was just too good to resist. The hubbub did not die down, and the debate meeting broke up.

See? I told you before that Lincoln was a funny man.

*Listen to the podcast version here or on Google Play, or subscribe on iTunes

Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and inspiration:

Ballance, Charles. The History of Peoria, Illinois. Peoria: N.C. Nason, 1870.

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999

Carwardine, Richard. Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Power. New York: Random House, 2003

Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995

Douglass, Frederick. The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, 1881.

East, Ernest E. Abraham Lincoln Sees Peoria: An Historical and Pictorial Record of Seventeen Visits from 1832 to 1858. Peoria, 1939

Garrett, Romeo B. Famous First Facts About Negroes. New York: Arno Press, 1972

Garrett, Romeo B. The Negro in Peoria, 1973 (manuscript is in the Peoria Public Library’s Local History & Genealogy Collection)

Herndon, William H. and Jesse W. Weik. Herndon’s Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life. 1889

Hoffman, R. Joseph. ‘Robert Ingersoll: God and Man in Peoria‘. The Oxonian, Nov 13, 2011

Hubbell, John T., James W. Geary, and Jon L. Wakelyn. Biographical Dictionary of the Union: Northern Leaders of the Civil War. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995

Kelly. John. ‘Robert Ingersoll, the ‘Great Agnostic’.’ The Washington Post, Aug 11, 2012

Kelly, Norm. ‘Peoria’s Own Robert Ingersoll‘, Peoria Magazines website, Feb 2016

Leyland, Marilyn. ‘Frederick Douglass and Peoria’s Black History‘, Peoria Magazines website, Feb 2005

Lehrman, Lewis E. Lincoln at Peoria: The Turning Point. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2008.

Lincoln Home National Historic Site, Illinois. Website, National Park Service

Peoria Register and North-Western Gazetteer, February 15, 1840, page 3. Library of Congress

‘Peoria Speech, October 16, 1854‘. Lincoln Home National Historic Site, Illinois website, National Park Service

Smith, Edward Garstin. The Life and Reminiscences of Robert G. Ingersoll. New York: The National Weekly Publishing Co, 1904

Wakefield, Elizabeth Ingersoll, ed. The Letters of Robert Ingersoll. New York: Philosophical Library, 1951

The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, W. Virginia, July 24th, 1899. From Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress

Pingback: To the Great Plains and Illinois I Go, in Search of Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, Abraham Lincoln, and Other American Histories | Ordinary Philosophy

Pingback: Peoria, Illinois, In Search of Robert G. Ingersoll, Frederick Douglass, and Abraham Lincoln, Part 2 | Ordinary Philosophy

Pingback: Photobook: Knockin’ on Freedom’s Door at Moses and Lucy Pettingill’s House Site in Peoria, Illinois | Ordinary Philosophy

Pingback: New Podcast Episode: Peoria, Illinois, in Search of Robert G. Ingersoll, Frederick Douglass, and Abraham Lincoln, Part 3 | Ordinary Philosophy

Pingback: From Oakland to Maryland, New York, and Massachusetts I Go, in Search of Frederick Douglass | Ordinary Philosophy

Pingback: Happy Birthday, Robert Ingersoll! | Ordinary Philosophy