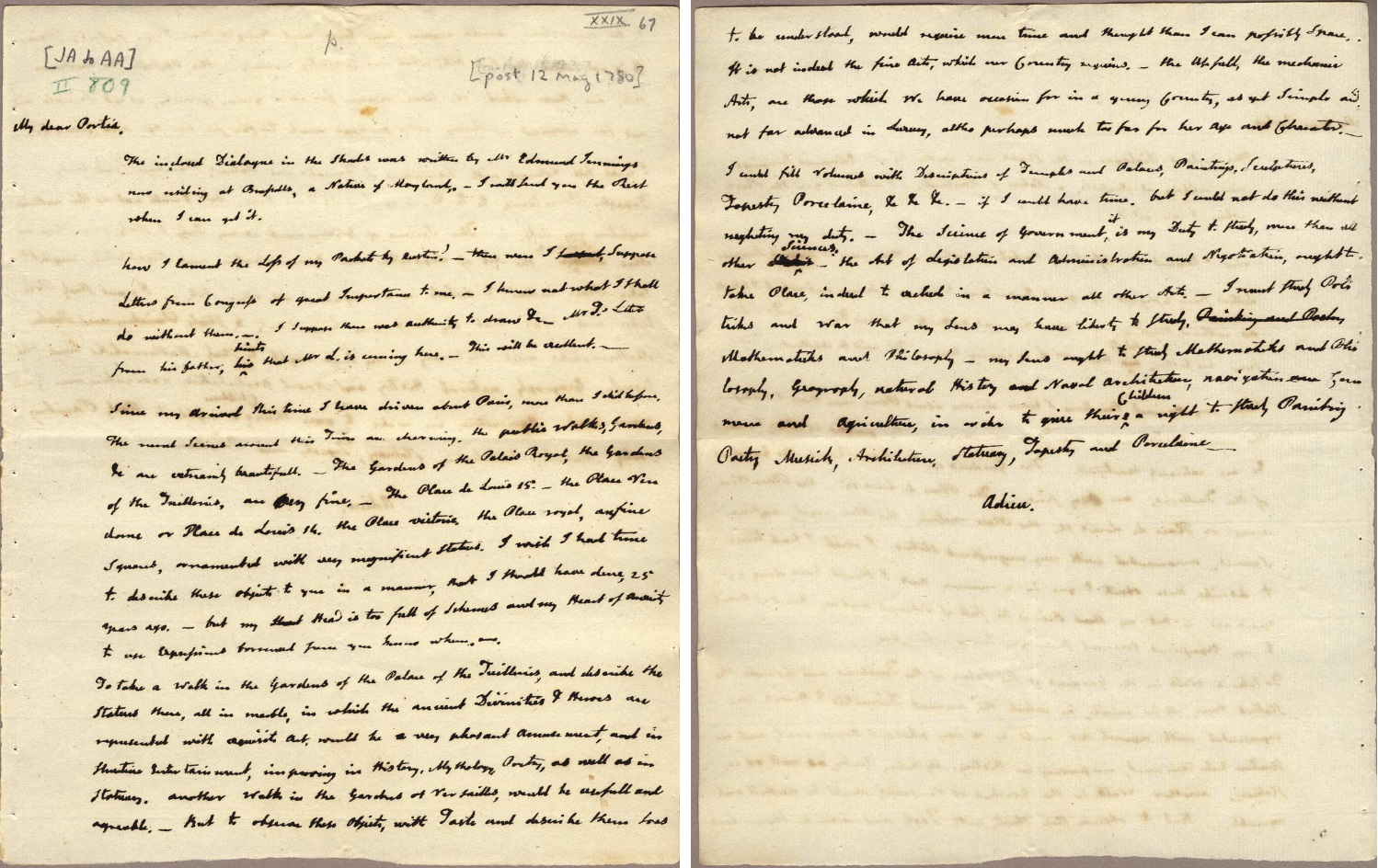

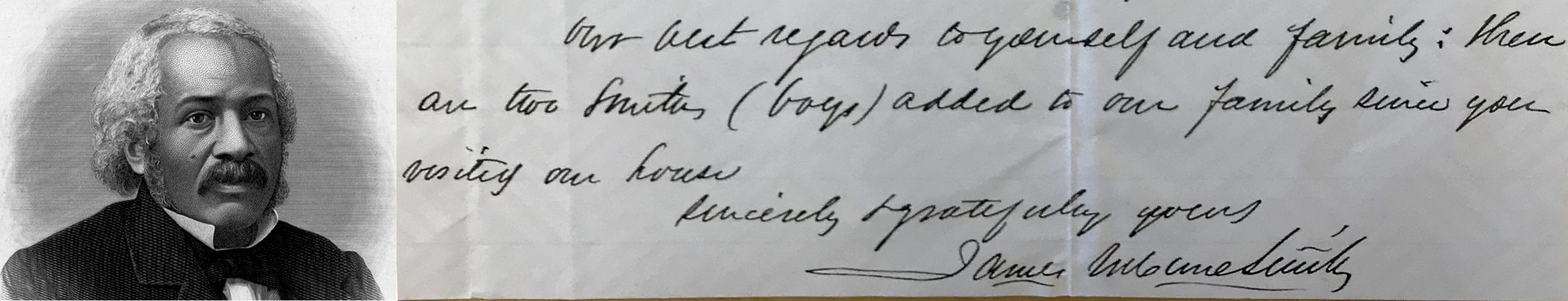

In the 1843 published version of his 1841 lecture “The Destiny of the People of Color,” African American physician, intellectual, author, classicist, and human rights activist James McCune Smith (1813–1865) reflected on the future of his oppressed people. From the midst of their shared struggle for freedom from slavery and prejudice, he found hope:

For we are destined to write the literature of this republic, which is still, in letters, a mere province of Great Britain. We have already, even from the depths of slavery, furnished the only music this country has yet produced. We are also destined to write the poetry of the nation; for as real poetry gushes forth from minds embued [sic] with a lofty perception of the truth, so our faculties, enlarged in the intellectual struggle for liberty, will necessarily become fired with glimpses at the glorious and the true, and will weave their inspiration into song. We are destined to produce the oratory of this Republic; for since true oratory can only spring from honest efforts on behalf of the right, such will of necessity rise amid our struggle. . . . In fine, we are destined to spread over our common country the holy influences of principles, the glorious light of Truth.(1)

McCune Smith’s predictions may have struck many readers as far too optimistic given the dire situation so many African Americans of his time faced, whether within the United States’ slave system or in the “caste” system it produced.(2) Even when not legally enslaved, nominally free African Americans were routinely denied access to education, lucrative jobs, good housing, transportation, and services, and they were almost universally denied equal political rights and representation. Yet McCune Smith’s observations of certain aspects of U.S. society and his political and sociological studies of past civilizations provided him with sources of hope and confidence for a better future for his people. This better future would center largely on the outsize role that African Americans would come to play, as they were sure to do, in the development of U.S. culture, especially in the artistic and intellectual realms.

In “Destiny,” McCune Smith expressed some of his observations within the context of analogies he drew from them. First, as a social and political activist as well as a devout Christian, McCune Smith observed that the clergy, largely excluded as they were from politics and the acquisition of wealth, nevertheless wielded great spiritual and moral influence. Therefore, they might have played more significant roles in the formation and development of U.S. society than those who wielded more direct political and economic power.(3) McCune Smith compared this soft power of the clergy to that which he believed African Americans held, or at least would come to hold. Likewise excluded from wealth and politics, in this case by law and by prejudice, African Americans had the moral sympathy of those who recognized that such oppressions contravened God’s law and the United States’ founding principles as outlined in the Declaration of Independence, which were likewise centered on moral, and therefore political, equality.(4) He predicted that as the general public recognized the logic and justice of arguments for equality, their sympathy must, then, necessarily increase, and with this, the moral influence of African Americans. As the above quotation confirms, McCune Smith saw the “influence of principles” as “holy,” and since the United States was founded on lofty principles rather than on nationality or ancestral considerations of birth and status, the principled fight for freedom and equal rights was holy as well—perhaps even more holy, and more inspirational, than the spiritual teachings of the clergy. Over time, this moral influence would change hearts and minds and bring about recognition of African Americans as human beings, equal in dignity and as deserving of rights as all other United States citizens.

None of this is to say that McCune Smith discounted the importance of direct political action or other sources of influence, such as increased access to the wider economy, greater social mobility, and more educational opportunities. He believed that African Americans had a right to these as well and worked hard throughout his life to facilitate their access to them.(5) Yet in “Destiny,” McCune Smith predicted that African Americans would likely win their equal place in United States society through moral victories first.

Looking to the past as well as the present, the classicist and political theorist McCune Smith drew another analogy: the struggle for equality by African Americans resembled freedom struggles in great republics of the past. As he observed, African Americans were routinely excluded from much of the “bustle of practical everyday life” within their own republic, the United States, through discriminatory laws and social practices.(6) African Americans were also, numerically, very much in the minority. Many other historical republics were founded on noble principles but oppressed those they conquered and enslaved; the latter usually represented the majority of the population, who rebelled once their oppression grew intolerable or a leader rose up to unite them. However, oppressed African Americans could not turn the tables on their oppressors by sheer force of numbers through violence or politics. Yet regardless, every republic that betrayed the principles on which it was founded inevitably came under the control of the people it had previously oppressed in one way or another.(7) McCune Smith believed that this same destiny awaited African Americans. It was their fate to dominate their oppressors, he insisted, because those oppressed by every republic throughout history, from the ancient Greeks onward, eventually did so.

Freedom from oppression did not historically come only from the downfall of oppressive republics. It also came from oppressed peoples finding their own ways to endure, then to succeed, and then finally to dominate. McCune Smith wrote,

The Jews, for example, in comparatively modern times have been persecuted and oppressed very much in almost every European kingdom. . . . And yet we find that the Jews, the so pitilessly oppressed minority, now hold in their hands the rule, the very fate of some of the kingdoms who were formerly foremost in persecuting them.(8)

Jewish people had found an avenue to freedom in finance, and Irish Catholics had found one through politics.(9) African Americans faced a different set of circumstances in their oppression, and they would therefore find another way. Because they were numerically a minority, and because the peculiar nature of their unconstitutional oppression primarily required intellectual and moral opposition, African Americans would also find themselves drawn to, as McCune Smith put it, “the more abstract studies,” removed from the mainstream struggle up the social ladder, fighting for justice all the while on intellectual grounds. In other words, instead of the struggle for rights and equality being a case of “might makes right,” African Americans could win only by demonstrating that, as McCune Smith phrased it, “right makes right.” Their bloodless victory would be not only a moral one but intellectual and artistic as well.(10) (McCune Smith came to believe that force was also necessary to end slavery; as it turns out, he was also prescient in that regard.)(11)

McCune Smith recognized signs that this African American artistic and intellectual revolution was not only to be glimpsed in the future; it was already beginning. For example, as he asserted in the quote which opened this essay, African Americans had created the first original form of U.S. music (more on this below), and they were “the source and subject of many essays, speeches, arguments &c., &c., which unfold with clearness and eloquence, true Republicanism to the prejudice-blinded eyes of the multitude.”(12) Though African Americans did not yet dominate the intellectual and artistic spheres, they had made inroads. This was especially impressive given the obstacles placed against their mere survival, let alone social, economic, and political advancement. African Americans largely refused to leave the land of their birth—because, as McCune Smith argued, “We are not a migrating people. The soil of our birth is dear to our hearts”; had shown their moral superiority over their oppressors by “returning Good for Evil”; contributed hugely to the nation through their labor; and flourished even in areas of the United States where the harshest and most prejudicial laws were arrayed against them.(13)

In many works throughout his literary career, McCune Smith would identify and celebrate the myriad ways in which African Americans took a leading and influential role in the development of U.S. art and culture, as well as the ways that people of African descent were influencing world culture more broadly. McCune Smith believed it was essential to explore, describe, and highlight the significance of the artistic and intellectual achievements of people of African descent throughout the world as well as in the United States to demonstrate how African Americans would come to dominate the nation’s artistic and intellectual culture. These demonstrations served not only to show how his optimistic predictions would come true for African Americans, but also to encourage them to “love, respect, and glory in our negro nature!” and thereby to not be dissuaded by prejudice from fulfilling their artistic and intellectual destiny.(14) As African Americans became more aware of the extent and significance of African contributions to artistic and intellectual culture around the world, their self-confidence would rise, enhancing their potential to fulfill McCune Smith’s predictions of their destiny in their own country.

In his “Lecture on the Haytien Revolutions,” published in 1841, McCune Smith celebrated the intellectual as well as the revolutionary legacy of Haitian freedom fighter Toussaint Louverture (1743–1803). Louverture’s legacy as a revolutionary was well known; McCune Smith believed it essential that his intellectual contributions be appreciated as well.(15) As well as being a skilled and inspired revolutionary leader, Louverture “had a mind stored with patient reflection upon the biographies of men, the most evident in civil and military affairs; and [was] deeply versed in the history of the most remarkable revolutions that had yet occurred amongst mankind.”(16) Louverture’s “lofty intellect” was expressed not in works of art and literature but in diplomacy, in his primary authorship of a new constitution, in his lawmaking, and in “his principles [which] were so thoroughly disseminated among his brethren.”(17) McCune Smith believed that much of the African American intellectual legacy would likewise be derived, directly and indirectly, from its own role in the struggle for freedom.

In his 1855 essay “The Critic at Chess,” McCune Smith described another way that people of African origin contributed to the arts, highlighting an example in which he believed Congolese warriors influenced white European literature. He perceived the rhythm and structure of a Congolese war chant within a stanza from Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem “Charge of the Light Brigade.”(18) McCune Smith chose a quote from author Gustave d’Alaux to demonstrate the chant’s influential and liberating power: “When these incomprehensible words . . . rolled out on the midnight air . . . the old St. Domingo planter had need to count his slaves, and the patrol to be on the alert” as it “transformed indifferent and heedless slaves into furious masses.”(19) Tennyson, McCune Smith believed, recognized its rousing power and translated that within his own expression of military rhythm.

Artists and intellectuals of African descent, as McCune Smith would describe, also revealed their power to touch the heart and mind and inflame the imagination beyond the realms of war and politics. In another 1855 essay, “The Black Swan,” McCune Smith paid tribute to the “genius” of U.S. singer Elizabeth Greenfield and French author Alexandre Dumas. The essay revolves around McCune Smith’s review of a Greenfield concert he attended at the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City, where the African American population suffered greatly due to legal and social discrimination, as they did throughout most of the United States.(20) Greenfield, whose popular moniker provided the title for the essay, nevertheless achieved a level of commercial success and widespread popularity few African Americans enjoyed, even in deeply prejudiced and segregated communities such as New York City. Dumas, McCune Smith wrote, was also a “first class original genius . . . of new proportions and unheard of fecundity of imagination” whose “grandest peculiarities are purely Negroid.”(21) Greenfield and Dumas were great artists whose ability to touch hearts and minds cut through and stepped over the petty boundaries that racial prejudice sought to erect around them. As pioneering music historian James M. Trotter wrote in 1878, “The haze of complexional prejudice has so much obscured the vision of many persons, that they cannot see . . . that musical faculties, and power for their artistic development, are not in the exclusive possession of the fairer-skinned race.”22 In his writings, McCune Smith showed how artists of African descent would open the people’s eyes and help them see past those prejudices: “True art is a leveler . . . never was the Tabernacle so thoroughly speckled with mixed complexions.”(23) As this example so well demonstrated, African Americans and peoples of African descent throughout the world would find that artistic and intellectual expression served as their most powerful weapon against oppression and marginalization in a prejudiced culture, and in dismantling the “caste” system that slavery had created.

Artists such as Greenfield and Dumas did not only break down racial barriers within their own times. As McCune Smith related, both artists, in part due to their unique racial heritage and their experiences in a prejudiced world, took their forms of artistic and intellectual expression to new heights, creating bodies of work that could only later be recognized for their true significance and thereby influencing and inspiring the work of future generations. McCune Smith wrote that Greenfield’s work as an innovative and consummate artist as well as an unapologetically “black woman” made her a “Priestess in the Temple” of the art world. She took her genre beyond what contemporary experience and sensibilities could appreciate, creating “a new revelation of Art [which] must be comprehended before it is chronicled in fitting terms.” Dumas did likewise with his literature, for which “the rules of European criticism are too small for the accurate measure of his proportions.”(24) Their accomplishments demonstrated the artistic and intellectual “influence which it shall be our [African and African American] destiny to possess.”(25)

McCune Smith believed that the analogies he drew among African American experience in the United States, the moral influence of the clergy, and various ways in which oppressed peoples liberated themselves; other lessons of history; and historical and contemporary examples of innovative and influential African-descended artists and intellectuals justified his prediction that African Americans would come to predominate in the development of many aspects of U.S. art and culture. Yet his predictions regarding the gamut of artistic expression and creativity were fulfilled to such a degree that even he, inspired with the confidence his words reveal, might marvel at it, as we can see in the following.

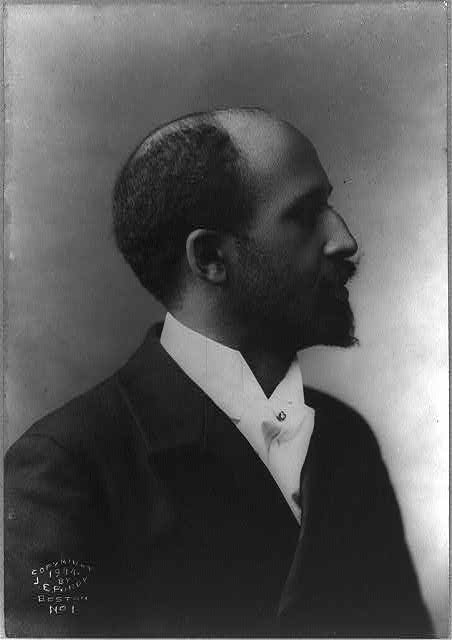

Since McCune Smith made his striking prediction nearly two hundred years ago, we have witnessed the rise to preeminence of African American artists, writers, intellectuals, ministers, scholars, orators, and poets. From journalists and educators Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells to activists, orators, and religious leaders Martin Luther King and Malcolm X; to intellectuals and authors W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, and Maya Angelou; to poets and playwrights Angelina Weld Grimké, Langston Hughes, Lorraine Hansberry, and Audre Lorde, to name only a very few, African Americans of letters, ideas, and oratory have played central roles in U.S. arts and culture. McCune Smith himself came to play an essential if still underrecognized role in creating the “Republic of Letters” that he envisioned in his 1852 essay “The Black News-Vender,” which he described as “that glorious commonwealth, perpetually progressive, free from caste . . . which smiles upon all her citizens, if they be but true, which holds triumphant sway and is crowned with perennial laurel in the coming ages!”(26) That essay forms but a tiny part of McCune Smith’s innovative and expansive body of work, which includes writings in medicine, science, history, social and political theory, rhetoric, biography, and social commentary.

In addition to his predictions in “Destiny,” McCune Smith made several other significant observations. One was that African Americans had, in his time, invented the only uniquely American form of music. He did not specifically identify this form, but from the quote which opens this essay (“We have already, even from the depths of slavery, furnished the only music this country has yet produced”), we can infer he meant songs which enslaved African Americans used to lighten the drudgery of enforced labor and which would give rise to many other forms of African American music. (27) While referring to a singular form may have been close enough to accurate in 1843, the myriad types of music invented, developed, or hugely influenced by U.S. citizens of African descent have multiplied by orders of magnitude. If it seems impossible to name every influential African American of letters and oratory, it seems even more impossible to name every influential African American musical artist. Such artists of creative and diverse genius as Scott Joplin, Memphis Minnie, Rosetta Tharpe, Ray Charles, Nina Simone, Prince, and Run-DMC created or refined genres of music that touch the heart, stir the soul, heat the blood, and move the body like no others. From spirituals to rap, from ragtime to jazz, from gospel to soul, from blues to rock-n-roll, from rhythm and blues to the Motown sound, from funk to hip-hop, these forms not only dominate American music but have become some of the most popular and influential throughout the world.(28)

McCune Smith saw much to be optimistic about in the long term regarding the great potential for human and specifically U.S. progress in interracial and intercultural connections, even as the political and social ramifications of race-based slavery and prejudice often left him weary, depressed, or in despair.(29) This potential would be realized most dramatically and forcefully, McCune Smith believed, in the realm of artistic and intellectual culture. The history of the United States following McCune Smith’s writings on African Americans in art and culture offers a multitude of vindicatory evidence of his deeply insightful predictions. While some fear the threat of artistic and cultural appropriation, African Americans have nevertheless “attain[ed] the influence” McCune Smith predicted.30 African Americans have indeed played a central and formative role in so many aspects of U.S. art and culture that a hypothetical United States devoid of their great contributions would be wholly unrecognizable and deeply impoverished.

The text of this article was originally published in Kalfou: A Journal of Comparative and Relational Ethnic Studies, Vol. 7 No. 1 (2020)

~ Ordinary Philosophy is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Any support you can offer will be deeply appreciated!

NOTES

- James McCune Smith, “The Destiny of the People of Color,” in The Works of James McCune Smith: Black Intellectual and Abolitionist, ed. John Stauffer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 59.

- In his essay “Civilization: Its Dependence on Physical Circumstances,” written in 1844 and revised for publication in 1859, McCune Smith defined “caste”—a term he used often—as “the general term for that feature in human institutions which isolates man from his fellow

man” (James McCune Smith, “Civilization: Its Dependence on Physical Circumstances,” in The Works of James McCune Smith, 261). - McCune Smith, “The Destiny of the People of Color,” 57–58.

- Ibid., 52–53.

- For more on McCune Smith’s community work and social justice activism and journalism, see Rhoda Golden Freeman, “The Free Negro in New York City in the Era before the Civil War” (Ph.D. diss.: Columbia University, 1966), 40–41, 46, 144–147, 184–186, 194, 196–197, 241, 247, 264, 270, 276, 305–306, 310, 352–354, 373.

- McCune Smith, “The Destiny of the People of Color,” 58.

- Ibid., 50–51, 54–55, 57–58.

- Ibid., 56–57.

- Ibid., 57.

- Ibid., 57–59.

- John Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 124; James McCune Smith, “James McCune Smith to Gerrit Smith, 1 / 31 Mar 1855,” March 1, 1855, Box 34. Gerrit Smith Papers, Syracuse University Libraries.

- McCune Smith, “The Destiny of the People of Color,” 55.

- Ibid., 51–53, 56.

- James McCune Smith, “The Black Swan,” in The Works of James McCune Smith, 120.

- For more about McCune Smith’s “promot[ion] of the black leader as intellectual, urbane, and historically conscious,” see Philip Edmondson, “To Plead Our Own Cause: The St. Domingue Legacy and the Rise of the Black Press,” Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies 29 (October 2005): 137–138, 140–142.

- McCune Smith, “Lecture on the Haytien Revolutions,” in The Works of James McCune Smith, 39.

- Ibid., 41–45.

- James McCune Smith, “The Critic at Chess,” in The Works of James McCune Smith, 110.

- Quoted in ibid., 110–111.

- Freeman, “The Free Negro in New York City in the Era Before the Civil War,” 435–436.

- McCune Smith, “The Black Swan,” 120.

- James M. Trotter, Music and Some Highly Musical People (Boston: Lee and Shephard, 1878), 4, available via the Internet Archive at http://archive.org/details/musicsomehighlym00trot. As well as a music historian, James Monroe Trotter (1842–1892) was an educator, a Civil War veteran from the 54th Massachusetts regiment, a postal worker, and the next African American following Frederick Douglass to serve as recorder of deeds for Washington, DC (William J. Simmons, Henry McNeal Turner, and A. G. Haven, Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising [Cleveland, OH: George M. Rewell, 1887], 833–842, available via the Internet Archive at http://archive.org/details/06293247.4682.emory.edu).

- McCune Smith, “The Black Swan,” 121.

- Ibid., 120–121.

- McCune Smith, “The Destiny of the People of Color,” 58.

- James McCune Smith, “The Black News-Vender,” in The Works of James McCune Smith, 190.

- McCune Smith, “The Destiny of the People of Color,” 59; Trotter, Music and Some Highly Musical People, 256, 263, 267, 324, 327.

- Burton W. Peretti, Lift Every Voice: The History of African American Music (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2009), 170.

- D. W. Blight, “In Search of Learning, Liberty, and Self Definition: James McCune Smith and the Ordeal of the Antebellum Black Intellectual,” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 9, no. 2 (1985): 19.

- McCune Smith, “The Destiny of the People of Color,” 58. Many theories, characterizations, and posited examples of cultural and artistic appropriation are problematic in many respects, especially in the way they so often conflate or obscure the differences between influence and emulation, which empower the artist or culture, and exploitation and failure to give credit, which disempower the artist or culture. This is not to dismiss widespread failures to credit artists and cultures for their creations, particularly in the music and fashion industries, or the fact that such practices are particularly problematic when it comes to historically disadvantaged groups. McCune Smith hinted at this problem when he identified Tennyson’s possible and uncredited adoption of the rhythm and structure of the Congolese chant in his poem “Charge of the Light Brigade.” It is important, however, not to lose sight of the fact that such exploitations and failures to give appropriate credit often occur within the wider context of popular recognition, admiration, and influence these historically disadvantaged artists and cultures have achieved. McCune Smith’s remarks about Tennyson’s poem also reveal his evident pride and satisfaction in the inspirational and influential power of the Congolese chant, including within the work of that Western poet whom McCune Smith so admired (McCune Smith, “The Critic at Chess,” 109–111).

‘

‘