Thursday, October 4th, 2018

This afternoon’s an exciting one: it’s the opening day of the Strike for Freedom exhibit at the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland. It features photos, letters, books, memorabilia, and more relating to Frederick Douglass and his family, friends, and colleagues, who spoke and worked for the abolition of slavery and equal rights in the antebellum United States and beyond.

Frederick Douglass is featured here at the NLS because he became an especially well-known abolitionist speaker in Scotland. Douglass traveled to the British Isles in August of 1845 following the publication of his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. He planned to kill two birds with one stone when he crossed the Atlantic: one, he would escape the danger of re-capture by his legal owner with the help of the information contained in the Narrative and two, he would add his voice to the growing antislavery movement in Britain. After touring Ireland, Douglass arrived in Ardrossan, Scotland on January 10th, 1846. Not long after his arrival, Douglass became involved in the ‘Send Back the Money!’ campaign, which called on the newly formed Free Church of Scotland to return donations from American congregations who supported slavery. Though the campaign did not succeed in persuading the Church to return the funds, Douglass’ speeches were immensely popular and he garnered a huge amount of support for the various causes he spoke for, including abolition, temperance, and equal access to public modes of transport and accommodations regardless of race.

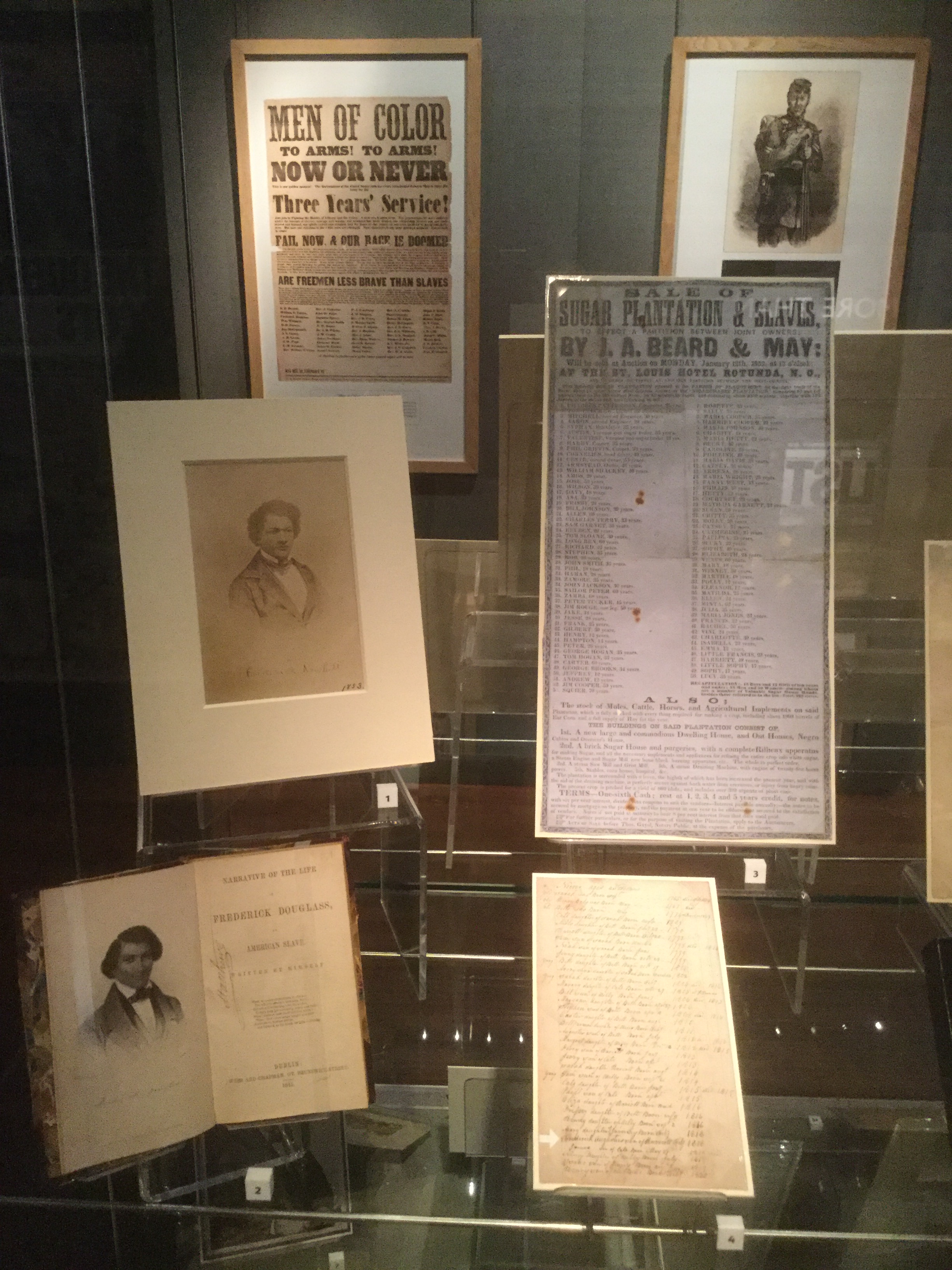

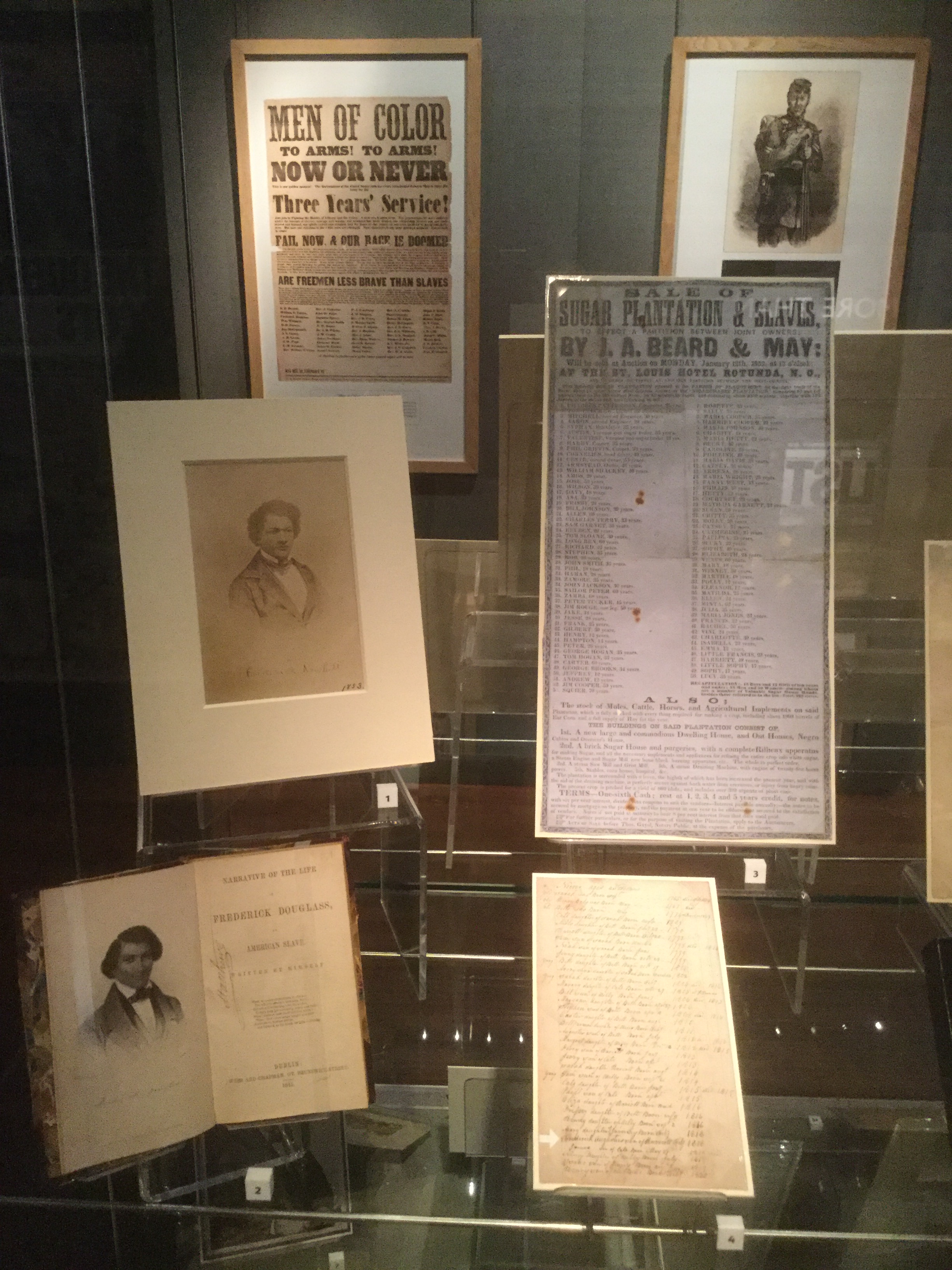

Frederick Douglass items in Strike for Freedom exhibit, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2018. At bottom left is the first Irish printing of Douglass’ Narrative, published by abolitionist Richard Webb, with a frontispiece portrait signed ‘B. Bell.’ Douglass hated the portrait, and though Webb took offense at Douglass’ reaction to it, he duly replaced it with another in subsequent printings. This is the very same copy from the NLS’ collection I consulted this summer when researching my master’s dissertation.

The Strike for Freedom exhibit’s opening is kicked off today with a fascinating and rousing talk by Celeste-Marie Bernier, who was instrumental in arranging this exhibit. The focus of her talk was how Douglass did not become the great man he was alone. His wife Anna Murray; his daughters and sons Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles Remond, and Annie; and his mother and grandmother Harriet and Betsy Bailey were all instrumental in helping him become the man he was. They functioned as inspirations, teachers, helpmeets, companions, consciences, correctives, encouragers, amanuenses, and above all, sources of love, pride, and joy for Frederick in every stage of his growth from slave child, to self-emancipated young man, to husband and father, to activist and author, to American statesman and moral leader.

The Strike for Freedom exhibit centers around Douglass family artifacts (mostly original with occasional facsimiles) from the Walter O. Evans collection. Dr. Evans and his wife Linda are major collectors of African-American art, but Dr. Evans has also gathered a massive collection of African-American documents, photos, and other artifacts throughout the course of his life. The exhibit also includes at least one item from the NLS’ own collection, and images from the Maryland State Archives, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Library of Congress, the Central Library of Rochester & Monroe County in New York, and the National Park Service’s Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in Washington, D.C.

Frederick Douglass in Edinburgh map, Strike for Freedom exhibit, National Library of Scotland, 2018

As I head for the exhibit after the talk, I pass by a large glass case with a map laid out, marked with pins and labels. It shows the location of Edinburgh sites associated with Douglass’ visits to Scotland. I’ll be covering these Edinburgh sites as I take my own journey through Edinburgh following Douglass, stay tuned!

Here are just some of the artifacts I saw in the exhibit. No doubt, I’ll be sharing more with you throughout my Douglass in the British Isles series as they relate to the stories.

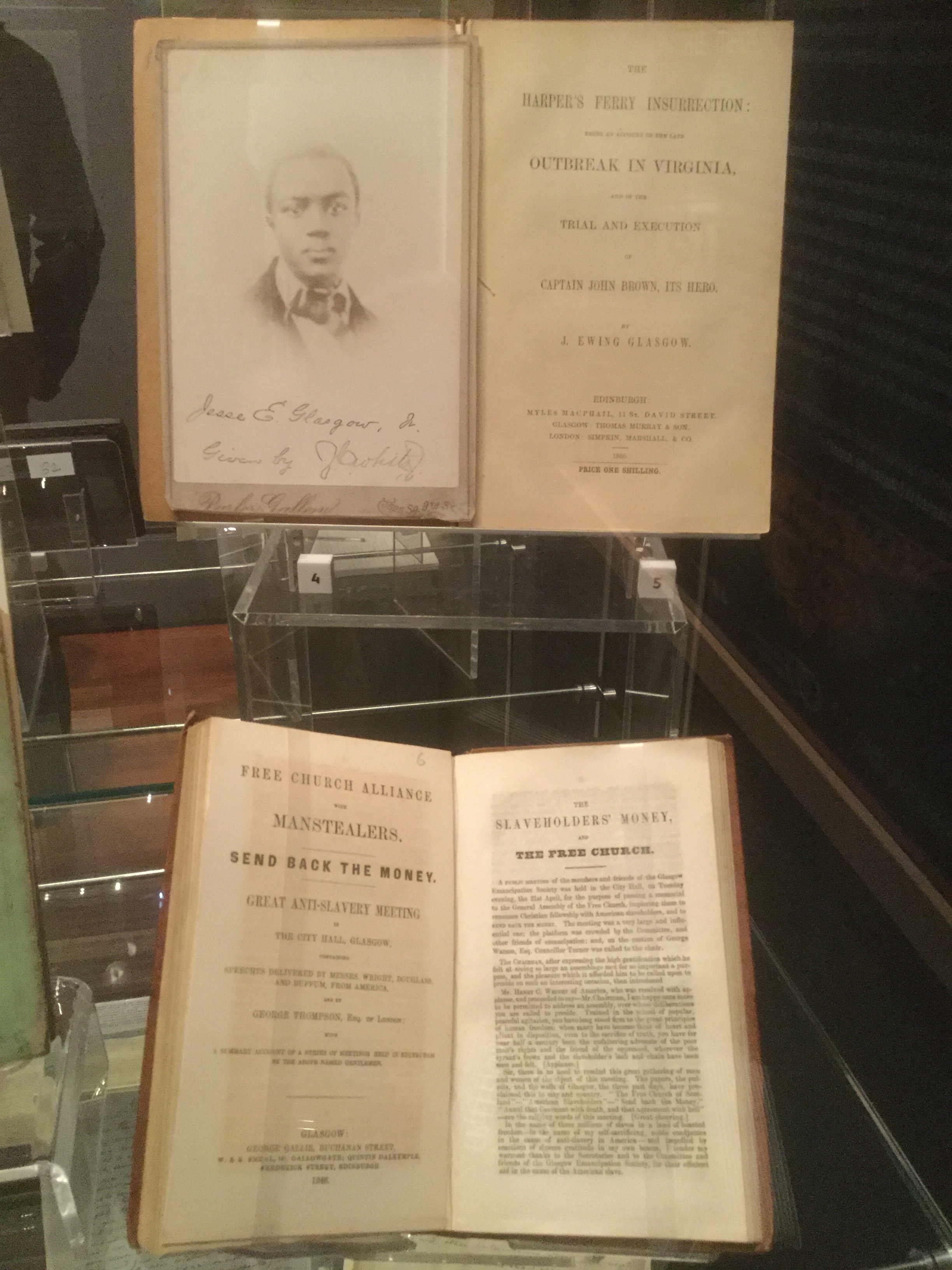

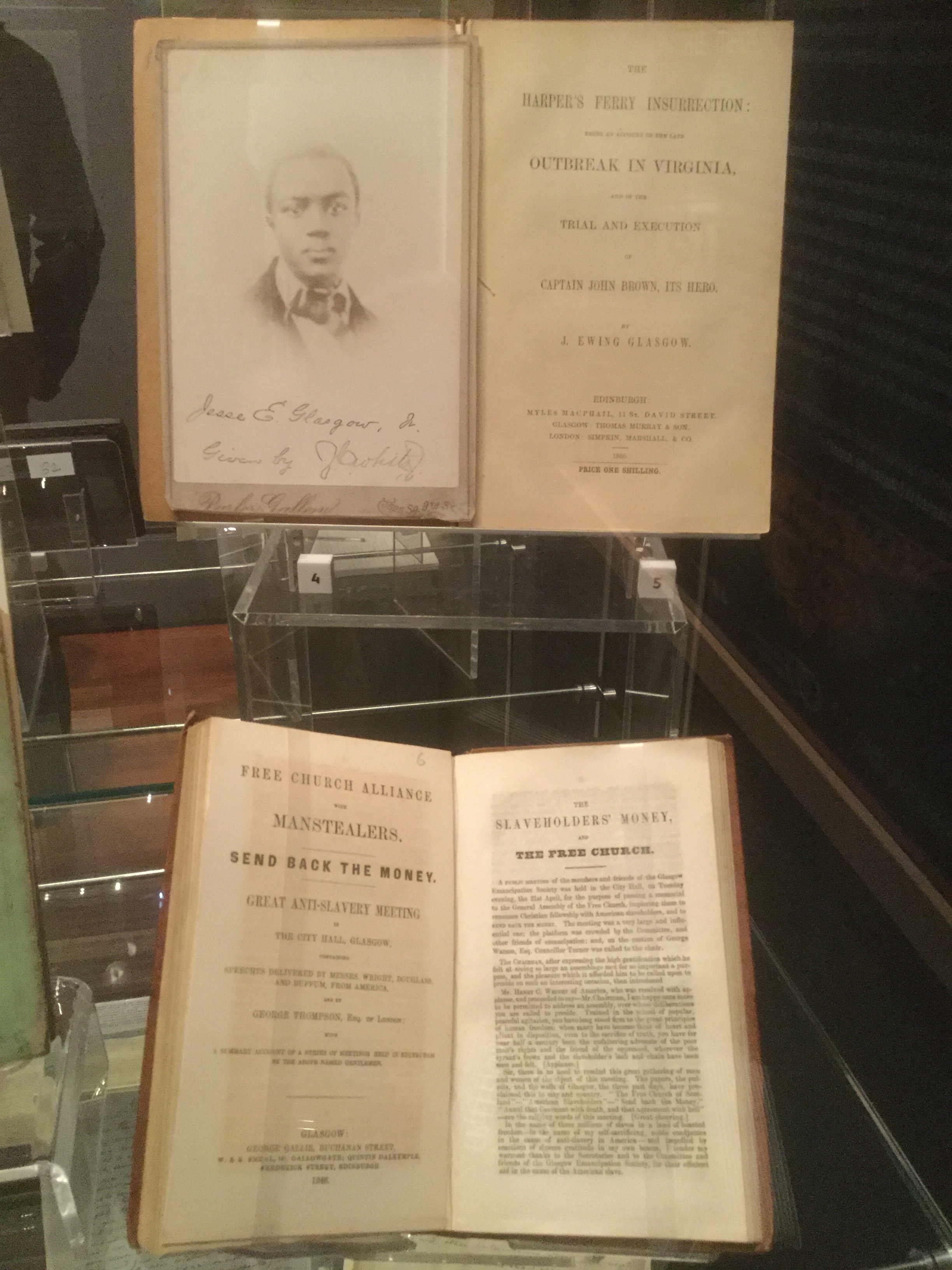

Jesse Glasgow’s book on Harper’s Ferry and John Brown and a ‘Send Back the Money!’ anti-slavery meeting pamphlet at the Strike for Freedom exhibit at the NLS, 2018. Glasgow was a classics student at the University of Edinburgh and unfortunately, died young in 1860, at only age 23, having already become a published author and an award-winning scholar.

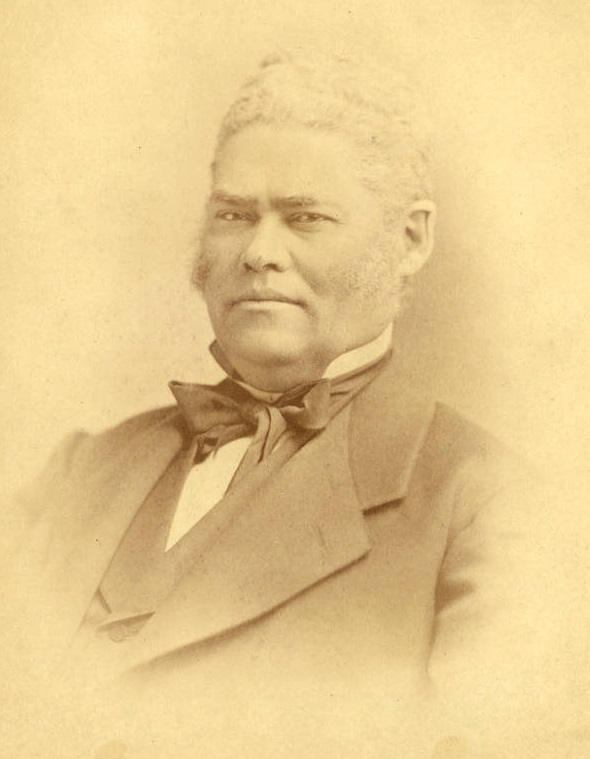

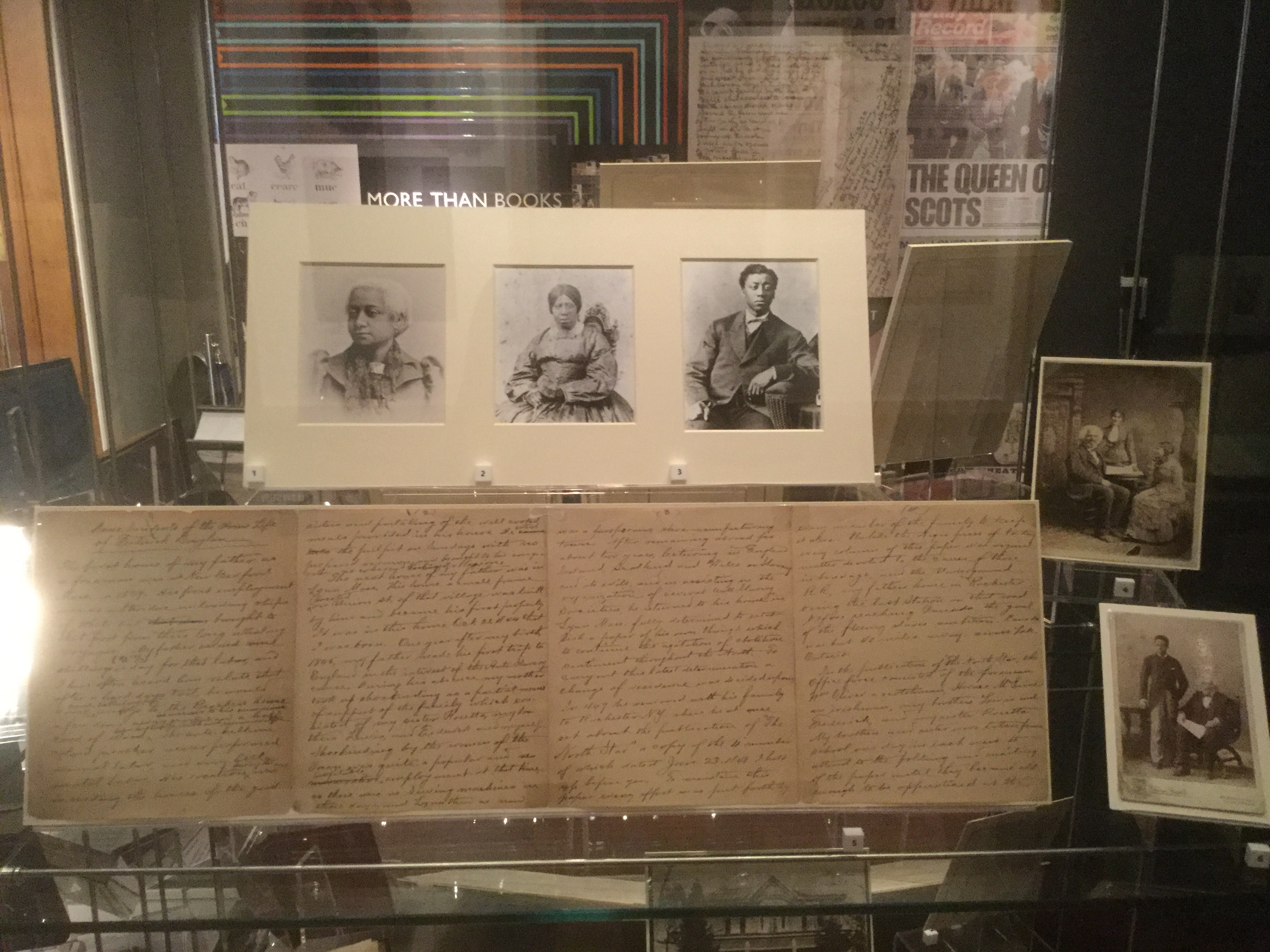

Lewis Henry and Helen Amelia Longuen Douglass photos and letter, Strike for Freedom exhibit at the NLS, 2018. Lewis was Douglass’ eldest son, and Amelia was a member of a prominent abolitionist family. The love letters between Lewis, away fighting in the Civil War, and his beloved Amelia tell a revealing and fascinating story of love among war and the fight for equality.

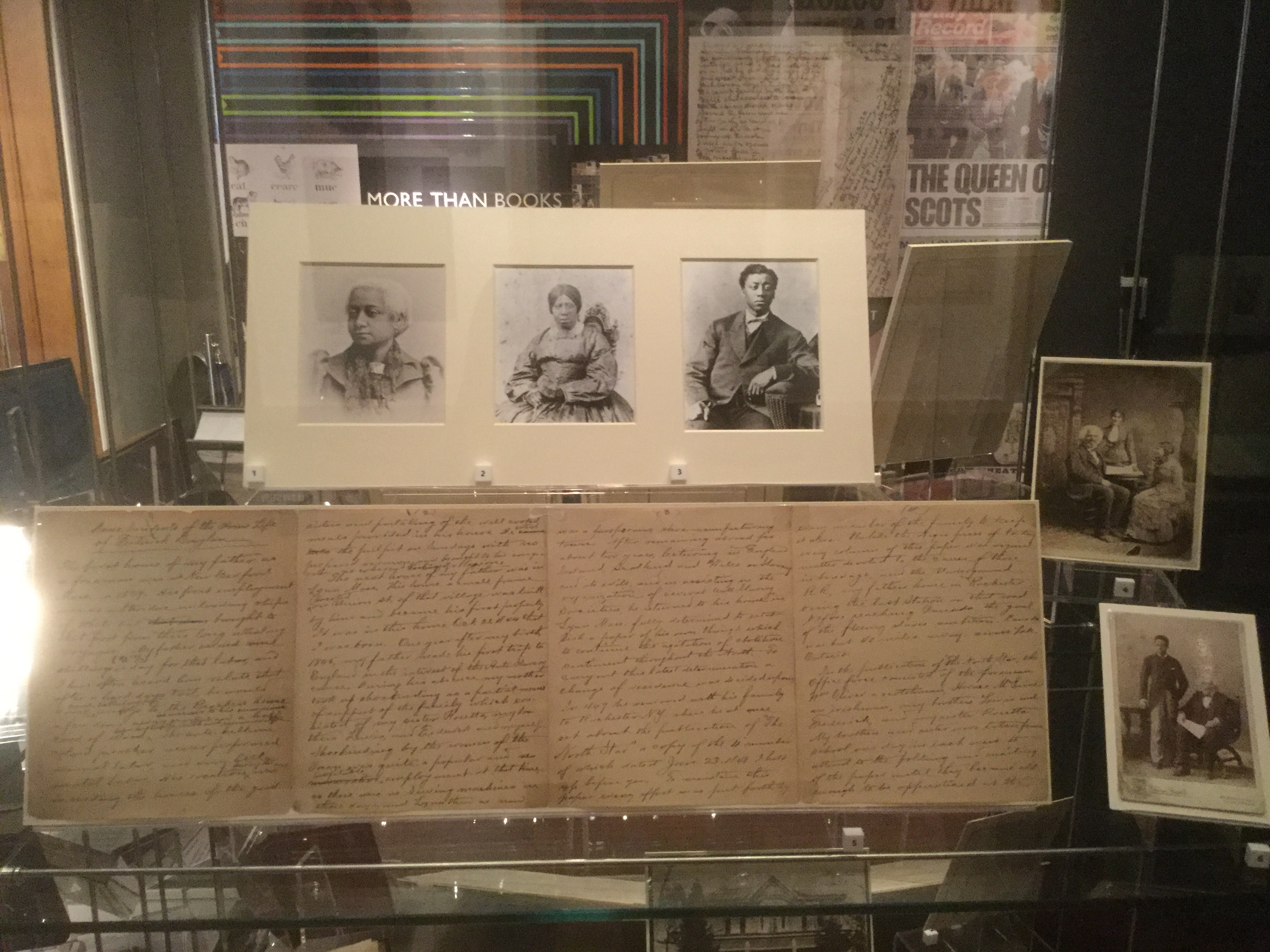

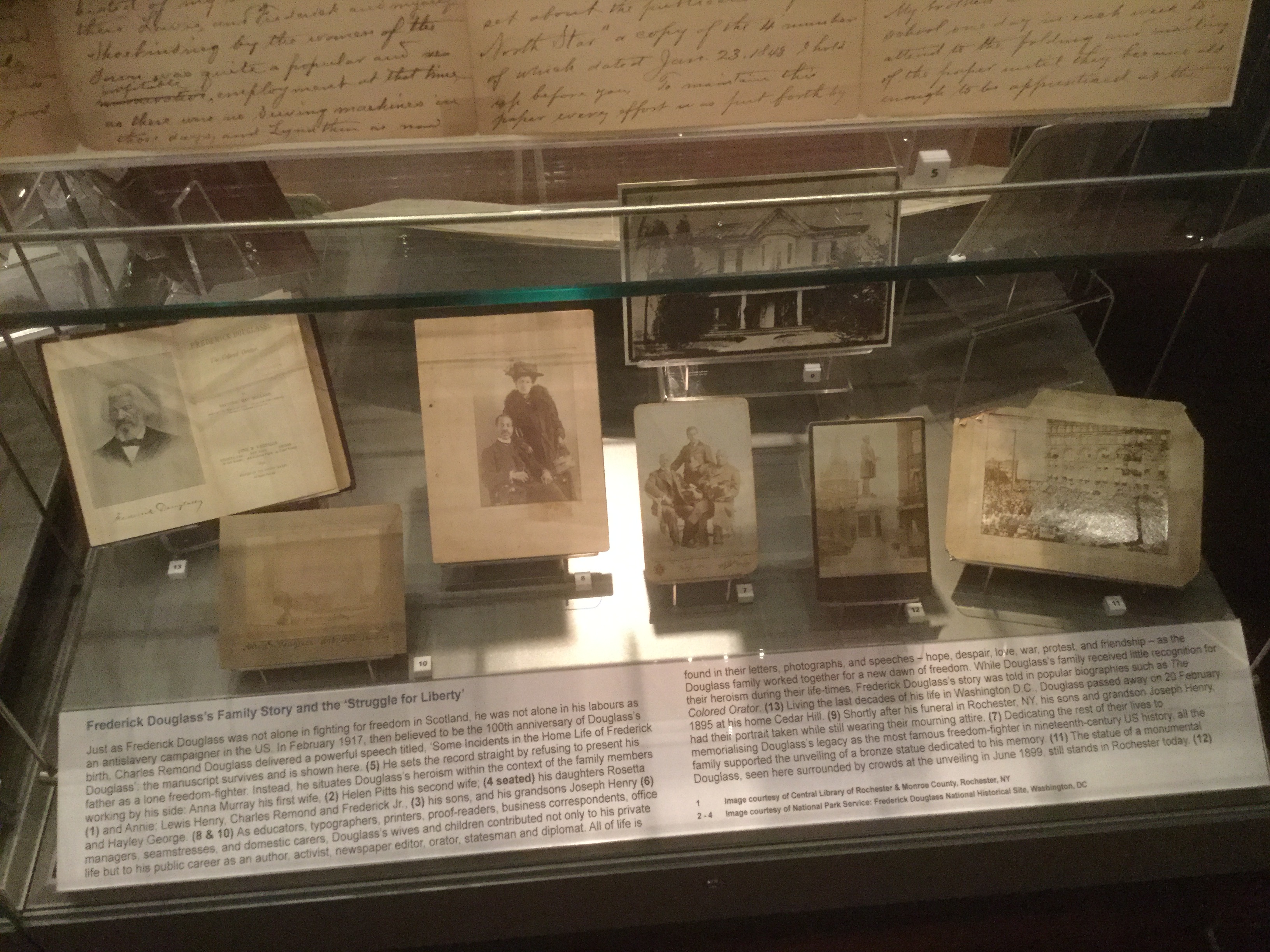

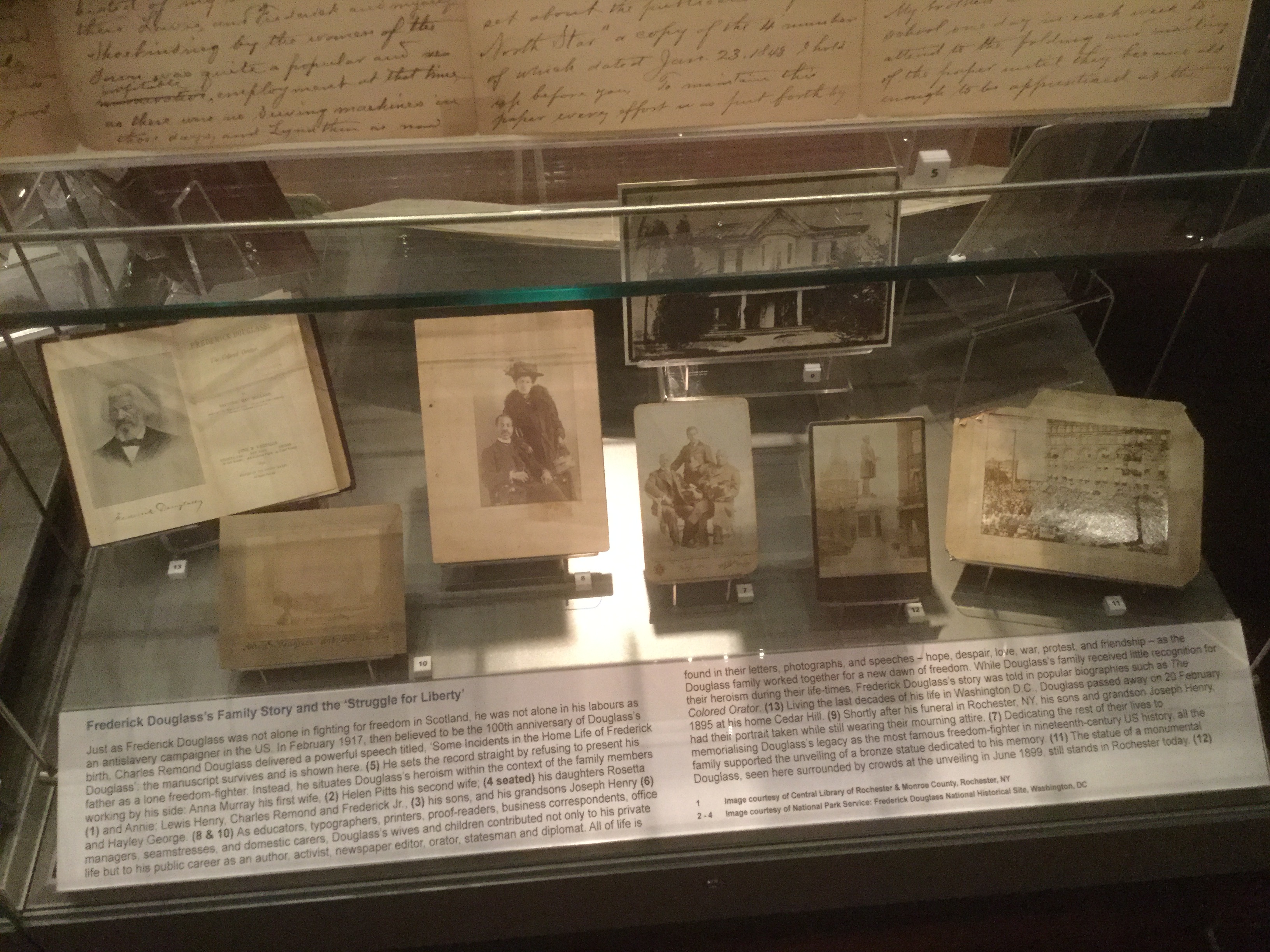

Frederick Douglass’ Family Story photos and artifacts at the Strike for Freedom exhibit at the NLS, 2018. At the top, from left to right clockwise, are pictured Rosetta, the Douglass’ eldest daughter; Anna Murray, Douglass’ first wife and mother of all of his children; the Douglass’ middle child Frederick Douglass, Jr.; Douglass with his second wife Helen Pitts (sitting) and her sister Eva (standing); and Douglass with his grandson Joseph (standing), a famous violinist. The four-page document is a speech written by Charles Remond Douglass titled ‘Some Incidents of the Home Life of Frederick Douglass’ in which he describes Douglass’ civil rights work as a family affair.

Frederick Douglass’ Family Story photos and artifacts, Strike for Freedom exhibit at the NLS, 2018

After a good long visit to the exhibit and chatting with some fellow attendees at the talk (including an all-too-brief chat with Dr. Evans), I depart, inspired, happy with the new things I’ve learned, and excited to continue my journey through texts and physical places following Douglass in the British Isles.

The National Library of Scotland’s Strike for Freedom exhibit will be continuing through February 16th, 2019.

~ Ordinary Philosophy is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Any support you can offer will be deeply appreciated!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and Inspiration:

Bernier, Celeste-Marie, and Andrew Taylor. If I Survive: Frederick Douglass and Family in the Walter O. Evans Collection. Edinburgh University Press, 2018

Delatinerjan, Barbara. ‘Interest in Black Art Just Grew and Grew.‘ New York Times, Jan 30, 2000

‘Jesse Ewing Glasgow, Jr. (c. 1837-1860)‘, Falvey Memorial Library at Villanova University website

Murray, Hannah Rose. Frederick Douglass in Britain and Ireland

Our Bondage and Our Freedom: An international project celebrating the 200 year anniversary of the birth of African American activist and author, Frederick Douglass. School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures, University of Edinburgh website

Pettinger, Alasdair. Frederick Douglass and Scotland, 1846: Living an Antislavery Life. Edinburgh University Press, 2018

Pettinger, Alasdair. ‘Douglass in Scotland‘ series for bulldozia.com