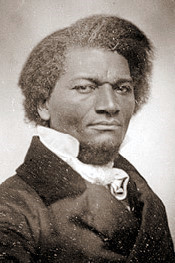

In his lifetime and to this day, Frederick Douglass is a hero to the religious and non-religious,to believers and skeptics alike, each claiming him as a champion and exemplar of their values. Why the discrepancy? In his speeches, letters, and published work, Douglass reveals himself as both believer and doubter, a man of deep Christian faith who experiences a great deal of religious skepticism throughout his life.

Douglass is a self-professed believer in God and a Christian, yet he’s a vocal critic of most Christian denominations of his day, especially those of the United States. As a young man, Douglass struggles with religious doubts as he observes, time after time, that the most pious slaveowners are the most cruel. His master Thomas Auld, Edward Covey the slave-breaker, Reverend Daniel Weedon and the neighboring Hamiltons in Baltimore, among others, routinely and mercilessly whipped and abused their slaves, often to the point of great injury and near death, all justifying their behavior through Bible passages. In his second autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass writes: ‘…The religion of the south…is a mere covering for the most horrid crimes…. Were I again to be reduced to the condition of a slave, next to that calamity, I should regard …being the slave of a religious slaveholder, the greatest that could befall me’ (159). In fact, he discovers to his surprise that the most decent master he ever had, William Freeman, was the only one without religion.

In his early days as an abolitionist activist and speaker, his accounts of his youthful doubts occasioned by his bad experiences with religious people cause many to accuse him of irreligion. But over time, he makes it clear that’s not religion itself he hates, it’s what he considers ‘false religion’. And no religion is as false as that which endorses slavery, which, first and foremost in Douglass’s time, was the Christian denominations of the American south.

But Douglass’s condemnation of American Christianity only begins with the southern churches; it by no means ends there. He calls on his fellow black people to leave any church, shaking the dust off their feet as they go, if their pastors or fellow parishioners subject them to indignity or unequal treatment. If anyone is segregated into balconies or back rows, or required to wait to receive communion after other colors or classes of parishioners, or their pastors preach against resistance to slavery, or the church in any other way indicates that black people are not deserving of the exact same respect, in degree and kind, as fellow children of God, then their church is revealed as just another peddler of false, corrupted religion. And all of these betrayals of the true Christianity, as Douglass perceives it, were as nearly pervasive in the northern churches as in the south.

Douglass believes that these practices, disrespectful of certain of God’s children, are not only unjust; they’re blasphemous because they’re direct attacks on the goodness and true nature of God. That’s because Douglass perceives the true God as not only ‘the God of Israel, Isaac, and Jacob’, but more broadly, the God of the oppressed. He sees this theme, this common thread, linking the plundered and oppressed desert tribes of Biblical Canaan (not mentioning that they did some plundering of their own) to those in his day who are suffering, reviled, and denied their natural rights: black people, women, the Irish, the abolitionists. Time and time again, Douglass relies on his interpretation of God as the God of the oppressed to show how the fugitive, the disenfranchised, the famine-starved left to die by their own governments, the righteous, reviled, and steadfast opposer of slavery and defender of the downtrodden, are actually those closest to him, are those who understand and share in his true nature.

But Douglass’s faith also appears at least as naturally derived as it is scripturally revealed. That’s because Douglass uses nature as a litmus test to reveal the truth and integrity of religion. Since by nature all people need and take joy in food and drink, physical and spiritual comfort, love, and beauty whatever their color, sex, or place of origin, and all people suffer alike from cold, hunger, thirst, cruelty, and neglect, and all people are just as capable of improvement through education and moral edification, then all people share the same nature, possess the same dignity, and have the same rights. Scripture may appear to allow for bigotry, unequal treatment, and bad behavior and even require it, but nature is observable and incontestable. So, if an interpretation of scripture seems to allow or require one to treat any of their fellow human beings as less than equally beloved, equally valuable children of the one God, that interpretation is certainly wrong since it violates the natural God-authored order of things.

In the end, Douglass relies on Jesus himself to tell us how to recognize true faith in true religion: ‘Wherefore by their fruits ye shall know them’ (Matthew 7:20). It’s not whether or not one professes belief in a religion, or can quote passages of scripture or the work of theologians, that reveals the worth and nature of faith. Douglass believes that true religion (which for Douglass, is true Christianity), always reveals itself by how well its adherents defend and promote justice and the equal dignity of all human persons. Conversely, if a religion commands or even permits injustice, it must be false. Where you find kindness and justice, there you find faith, and nowhere else.

It’s not the outward form or classification which indicates the true tree of religion to Douglass, it’s the sweetness and wholesomeness revealed in the fruit of true faith.

*Listen to the podcast version here or on iTunes

*Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and is ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and Inspiration:

Douglass, Frederick. The Heroic Slave: A Cultural and Critical Edition. Eds Robert S. Levine, John Stauffer, and John McKivigan. Hew Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom: 1855 Edition with a new introduction.. Re-published 1969, New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Foner, Philip S. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. 1-4. New York: International Publishers, 1950.

Pingback: From Oakland to Maryland, New York, and Massachusetts I Go, in Search of Frederick Douglass | Ordinary Philosophy

Pingback: Frederick Douglass New Bedford, Massachusetts Sites | Ordinary Philosophy