Etching of the old Peoria County Courthouse on a granite wall at the new one, Peoria, IL. It shows the portico from which Lincoln delivered his famed Peoria Speech of October 16th, 1854

Peoria, Illinois, July 28th, 2017, continued

~ Dedicated to Shannon Harrod Reyes

I leave the library and begin my afternoon’s site searches at the Peoria County Courthouse. Abraham Lincoln visited this courthouse many times over the years, on some occasions in his capacity as a lawyer and other times in association with his political career. There’s a statue of Lincoln here commemorating a particularly notable occasion: his delivery of a speech from the front portico of the old courthouse on October 16, 1854. This speech was composed and delivered in opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, co-authored by Stephen A. Douglas. The Peoria Speech, as it’s now known, was part of a series that took place during that legislative election season where Douglas and Lincoln addressed and rebutted each other’s arguments, sometimes during the same event, sometimes separately. Their exchange would be revived four years later, notably in the series of seven formal debates of 1858. Douglas won that year’s Senate election with 54% of the vote, but Lincoln distinguished himself so well in that campaign season that he won the larger prize two years later. He was elected President in 1860, handily defeating his closest rival Douglas with a 10%+ lead.

The Peoria County Courthouse as it appears today, Peoria, Illinois

It was this 1854 speech delivered here in Peoria, however, that’s widely credited with first putting Lincoln on the political map in a big way. Lincoln had mostly withdrawn from politics, having served many years in the Illinois state legislature but only winning one term in higher office in 1846 in the United States House of Representatives. The furor over the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise and opened the door to the expansion of slavery, drove Lincoln back into politics, by his own account. He had always been rather reticent about the slavery issue, concerned that too much controversy over it would destabilize the country. The recent passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act was only one of the many major events that revealed the controversy was unavoidable.

The Trial of John Brown by Horace Pippin, 1942 at the De Young Museum, San Francisco, CA. John Brown was one of those who led abolitionists into Kansas territory to combat pro-slavery advocates, and in the process, indiscriminately killed pro-slavery settlers. He led the unsuccessful raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859 and was executed for treason.

For one thing, Kansas-Nebraska Act’s underlying political doctrine of popular sovereignty, where the states could decide on the legalization of slavery themselves by vote, led to such extreme regional disputes as Bleeding Kansas. People flooded into the territory (Kansas was not yet a state) to push the vote one way or another through violence as well as numbers. Those on the pro-slavery side wanted to preserve the political power of the slave states and to be able to settle in Kansas with their slaves if they so chose. Those opposing slavery wanted to keep slavery out of Kansas as a matter of principle and, more often, to make it a place where people could make a new life for themselves without having to compete with slaves for jobs and with wealthy slave-plantation owners for land.

Secondly, while attractive to many from both sides at first glance, the principle of popular sovereignty revealed its weaknesses over time and proved deadly to Douglas’ political career. Abolitionists and other free state citizens did not want to abide by fugitive slave laws which required that free states return escaped slaves, and did not want to protect the right of visitors to own slaves within their borders. They saw this as an imposition of slavery into territories that abolished it. Slave states regarded the refusal to return escaped slaves as an attack on their property rights, and an unfair limit on their right to travel freely from state to state. Popular sovereignty turned out to harm, not help, the cause of preserving the Union.

Statue of Abraham Lincoln outside the Peoria County Courthouse commemorating his Oct 16, 1854 speech here

The Peoria speech was Lincoln’s second public delivery of his first detailed and straightforward denunciation of slavery on moral grounds. While the speech did not promote the national abolition of slavery, Lincoln made the historical case that Thomas Jefferson was a reluctant slave-owner caught up in a social institution that he abhorred, but like slave-owners of Lincoln’s day, he felt trapped in it. So, Jefferson hoped and planned for its gradual dissolution. He used his influence to make sure the Northwest Ordinances of 1787 and ’89 banned slavery in all new territories of the United States, shifting the balance of political power away from the slave states and towards those states whose prosperity resulted from the industry of free people. Lincoln argued that continuing to prevent the spread of slavery was the only way to realize Jefferson’s hope while doing what was politically possible to assuage the evils of slavery until it faded away naturally. Though we, with Frederick Douglass, might be scornful of and impatient with Lincoln’s apparent have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too attitude towards slavery as a terrible moral evil but allowable in the South if it held the Union together, the speech contains the outline of the basic moral principles underlying Lincoln’s increasingly anti-slavery platform as his presidency and the Civil War progressed.

The version of the Peoria speech that’s come down to us was transcribed by Lincoln himself for publication in Springfield’s Illinois Daily Journal, in seven issues on October 21st, then the 23rd-28th, 1854. This is lucky for us as few transcripts of that series of exchanges between Douglas and Lincoln survive. Lincoln had delivered the first version of this speech in Springfield and had clarified and refined it, as well as making a few changes to tailor it to the Peoria audience.

Commerce Bank at the approximate site of old Rouse’s Hall at Main St and Jefferson Ave, Peoria.

Frederick Douglass ambrotype, 1856, by an unknown photographer, image public domain via Wikimedia Commons. He spoke in Peoria in Rouse’s Hall about three years after this picture was taken.

Then I head to Jefferson and Main, to the site of Rouse’s Hall. Frederick Douglass lectured here on February 25th, 1859, and according to the Peoria Daily Transcript newspaper, his speech was so well received that Douglass decided to add a follow-up one a few days later. The Transcript reported that ‘appreciative and intelligent’ audience braved the weather in large numbers to hear this famous orator speak.

In the first speech, Douglass presented his argument that all human races had a common origin, supporting his views with ‘history, philosophy, and science’. He was not making a Darwinian case since On the Origin of Species would not be published until the fall of that same year. The Transcript also reported that the speech included an argument about slavery which ‘he had not yet exhausted,’ so presumably Douglass was presenting the larger case that since all human beings belong to a common natural family, there can be no claims of superiority that would justify one branch of this family oppressing another.

In their notice of the second speech scheduled for March 1st, the Transcript predicted that the crowd would be even larger, given the enthusiasm of the audience during the last one and the fact that this one was better advertised. They also confirmed that Douglass revealed the true ‘heinousness of Slavery’ by showing how black and white people belonged to the same human family, with the same ‘inherent faculties of the soul.’ Douglass, proclaimed the Transcript, was living proof that natural genius is to be found in all races in equal measure, and all it takes for the black race to achieve its potential and improve their faculties is to enjoy equal access to all that culture has to offer. One of the ways for his fellow black citizens to do so, Douglass said, was self-improvement: since they were not given equal chances to improve themselves, they must take their chances into their own hands as far as possible until legal and social equality was achieved.

Writing about ‘Our Recent Western Tour’ in Douglass’ Monthly, published the next month of April, 1859, Douglass spoke optimistically of the future, based on the mostly warm welcome he and his fellow speakers had received during the tour. In years past, he had often been subject to humiliation and rude treatment by audience members and people of the towns he traveled to. This time, he wrote, they were usually treated with courtesy, respect, and friendship, and the number of committed abolitionists seemed to be ever-increasing. As Douglass wrote, ‘We think a Negro lecturer an excellent thermometer of the state of public opinion on the subject of slavery…’ Though he found the overall temperature warming, he still encountered some chill between-times, as the next story will reveal.

Rouse’s Hall, image courtesy of Peoria Public Library

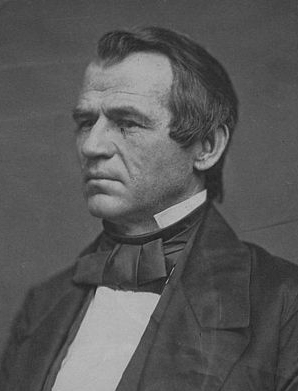

Robert Ingersoll in 1868. This photo would have been taken around the time that Frederick Douglass would have called on him in Peoria, when Ingersoll was about 35 years old, a married father of two, and the Attorney General of Illinois.

This also happens to be one of my favorite stories about Robert Ingersoll. It likely occurred during one of Frederick Douglass’ return visits here for an 1867 speech at Rouse’s Hall. This year is consistent with Douglass’ account: it must have happened in the late 1860’s since Douglass wrote it was ‘a dozen years ago or more’ in his final autobiography, 1881’s The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. For all of the Transcript’s glowing review of his speeches and the audience’s enthusiasm, Douglass recalled finding little welcome offstage here on his first visit, so he dreaded going back. Perhaps he wouldn’t even be able to find a hotel that would accommodate him at all! Douglass mentioned this to a friend who he was staying with in Elmwood, a previous stop on his speaking tour. This friend said to him, ‘I know a man in Peoria, should the hotels be closed against you there, who would gladly open his doors to you – a man who would receive you at any hour of the night, and in any weather, and that man is Robert J. Ingersoll.’ (He got the middle initial wrong.) Douglass expressed concern about disturbing his family and was glad he didn’t have to since the ‘best hotel’ gave him a room. But he was intrigued his friend’s description of Ingersoll’s hospitable and unbiased personality, and about his ‘infidel’ views (these quotes are Douglass’ own, presumably tongue in cheek. Douglass was a religious skeptic in many ways himself). So Douglass went to call on the Ingersoll family at home the next morning. Douglass went on to describe the warmth of his welcome in fulsome terms, and to point out that this ‘infidel’ gave him a more Christian welcome than anyone who would define themselves that way ever had. His impression of Ingersoll’s face with its expression of ‘real living human sunshine’, I notice as I reread Douglass’ story, accords with the one I wrote in the first part of this account: ‘He has the face of a ready and kindly friend.’

In that March 6th, 1867 speech at Rouse’s Hall, Douglass spoke of the temperature dropping once again. The Civil War had ended just under two years before, and the North had not yet sorted out what they perceived as ‘the Negro problem.’ Even many of the most ardent Abolitionists were not ready to accept black people as equal members of their own communities. Like Lincoln had for most of his life, they considered slavery wrong but didn’t think that black and white people were fully if at all compatible as friends, coworkers, fellow politicians, and so on; certainly not as romantic partners. And many still thought condescendingly of freed black people as some kind of amorphous mass of downtrodden creatures that should be humbly grateful for the new freedoms that were bestowed on them, and therefore not demand too much. Douglass, of course, rejected this view. Black people had fought, and fought hard, for their own freedom, and those who fought with them, while brave and often motivated by sincerely held moral beliefs, were also acting in their own interests. The test of whether the emancipation of the black race was a true one, consistent with our American principles laid out in our founding documents, was to see how well the United States protected the rights of black people from there on out.

Parking lot where Robert Ingersoll’s mansion and then the National Hotel used to stand, at the north corner of Jefferson Ave and Hamilton St, kitty-corner from the Peoria County Courthouse

Period view of Robert Ingersoll’s grand house at Jefferson and Hamilton, image from the Robert Ingersoll Birthplace Museum webpage

In 1876, Robert Ingersoll took his law practice solo and moved his office into his third and final Peoria home at the corner of Jefferson Avenue and Hamilton Street. The Ingersoll family lived here until they returned to New York in 1877. All three locations of Ingersoll’s homes, by the way, are taken from Edward Garstin Smith’s The Life and Reminiscences of Robert G. Ingersoll. Smith provides street corners and some landmarks, but since he gives us no street numbers, doesn’t specify north, south, east, and west, and most of the landmarks have changed, I don’t always know just where to photograph. He does tell us that the National Hotel was later built on the site of this home, and Ingersoll’s ‘splendid mansion,’ a four-story affair, was ‘moved to the side of the lot’ of the hotel. Then, with further digging, I find an old postcard of the National Hotel site on the Local History and Genealogy Collection of the Peoria Public Library’s website. Once again, they come through admirably!

Peoria National Hotel postcard, pre-1911, courtesy of US Genealogy Express. This hotel was built on the site of the Ingersoll family’s third and final home in Peoria.

Another image of the New National Hotel at the former site of Robert G. Ingersoll’s home at the northeast corner of Jefferson & Hamilton. It was built 1883 and razed in 1970, having suffered a fire. It’s now a parking lot. Local History and Genealogy Collection, Peoria Public Library, Peoria, Illinois

Corner of Main and Jefferson, Peoria, IL, pre-WWI, Local History and Geneology Collection, Peoria Public Library, IL.

The first home of Ingersoll in Peoria, which he rented, was in the 100 block of North Jefferson Ave, between Main St and Hamilton Blvd, and at the time Smith wrote his biography of Ingersoll, the site was occupied by the YMCA building. This site would likely be across the street from the Courthouse square; it’s my understanding that no other buildings ever occupied the square, based on all the old photos and atlases I could find of Peoria. That would place it somewhere near the Rouse’s Hall site, perhaps to the north of it where the tall building next to Commerce Bank is now. (See the Commerce Bank at Main St and Jefferson Ave photo above.)

N. Jefferson Ave between Hamilton and Fayette. Ingersoll’s second house in Peoria stood about where the first building on left does now

Ingersoll’s second home, which he also rented, was on North Jefferson Ave as well, on the 200 block between Hamilton and Fayette. It was still standing when Smith wrote his biography in 1904. This may be where Ingersoll lived when he met and married his wife, and perhaps where they lived when their daughters were born; Smith doesn’t provide a timeline for their moves between each house. Ingersoll married Eva Amelia Parker in February 1862, and his daughters Eva Robert Ingersoll and Maud Robert Ingersoll were born in 1863 and 1864, respectively. So he had already completed his time of service in the Civil War then he settled down to make a family with Eva.

As I’ve written before, Ingersoll was a dedicated family man. He spoke eloquently and movingly of the joys of family life. It was a home filled with love and mutual respect, by all accounts. No wonder Ingersoll’s face almost invariably looks so amiable and friendly in photos! There’s a card I discover among the digital archives from the Robert Ingersoll Papers in the collection of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library which includes a photograph of Ingersoll cuddling two of his grandchildren over a poem he wrote titled, simply, ‘Love.’ I’ll leave you with this as I end this part of my account of my day in Peoria, and I’ll pick up the rest of the tale very soon…

Farrell, C. P., “Robert Ingersoll, Love,” Chronicling Illinois, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library

*Listen to the podcast version here or on Google Play, or subscribe on iTunes

Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and inspiration:

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999

Carwardine, Richard. Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Power. New York: Random House, 2003

Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995

Douglass, Frederick. The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, 1881.

East, Ernest E. Abraham Lincoln Sees Peoria: An Historical and Pictorial Record of Seventeen Visits from 1832 to 1858. Peoria, 1939

‘Electoral history of Abraham Lincoln‘. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

Foner, Philip S. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. II. New York: International Publishers, 1950.

Garrett, Romeo B. Famous First Facts About Negroes. New York: Arno Press, 1972

Garrett, Romeo B. The Negro in Peoria, 1973 (manuscript is in the Peoria Public Library’s Local History & Genealogy Collection)

Herndon, William H. and Jesse W. Weik. Herndon’s Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life. 1889

Hoffman, R. Joseph. ‘Robert Ingersoll: God and Man in Peoria‘. The Oxonian, Nov 13, 2011

Insurance Maps of Peoria, Volume 1. Sanborn Map Company of New York, 1927. (Showing the street numbers before they changed in 1958)

Kelly, Norm. ‘The Hall That Rouse Built‘, Peoria Magazines website, Feb 2015

Kelly, Norm. ‘Peoria’s Own Robert Ingersoll‘, Peoria Magazines website, Feb 2016

Leyland, Marilyn. ‘Frederick Douglass and Peoria’s Black History‘, Peoria Magazines website, Feb 2005

Lehrman, Lewis E. Lincoln at Peoria: The Turning Point. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2008.

‘Lincoln Draws the Line’, Peoria, IL – posted by KG1960 on Waymarking.com

Lincoln, Abraham. ‘Peoria Speech, October 16, 1854.’ via the National Park Service’s Lincoln Home National Historic Site website and ‘Abraham Lincoln’s speech at Peoria, Illinois: [Oct. 16, 1854] in reply to Senator Douglas‘. Seven numbers of the Illinois Daily Journal, Springfield, Oct. 21, 23-28, 1854. [Peoria, Ill.: E. J. Jacob]

Lincoln Home National Historic Site, Illinois. Website, National Park Service

MacMillan, Lois. ‘Close Reading: Speech at Peoria, October 16, 1854‘, published at Quora: Understanding Lincoln

Peck, Graham. ‘New Records of the Lincoln-Douglas Debate at the 1854 Illinois State Fair: The Missouri Republican and the Missouri Democrat‘. Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Volume 30, Issue 2, Summer 2009, pp. 25-80

‘Peoria Speech, October 16, 1854‘. Lincoln Home National Historic Site, Illinois website, National Park Service

Smith, Edward Garstin. The Life and Reminiscences of Robert G. Ingersoll. New York: The National Weekly Publishing Co, 1904

Wakefield, Elizabeth Ingersoll, ed. The Letters of Robert Ingersoll. New York: Philosophical Library, 1951

The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, W. Virginia, July 24th, 1899. From Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress