A view of downtown Albany, New York, looking west

Eighth Day, Sunday March 27th

I get up very early and leave Cambridge (where I’ve been staying while visiting Boston and Lynn) and this time, instead of heading north, I head west across upstate New York. I’ve never visited this part of the country before. My friend who I’ll be staying with in Rochester laments that I’m visiting at the least advantageous time of year for beauty’s sake: the snow is gone, and having scrubbed the trees bare, leaves the trash it’s been concealing exposed, and there’s not a hint of green nor bloom yet on the branches. But I still think it’s lovely, with a sort of stark gray beauty, and enjoy the day’s drive of about 325 miles.

My first stop is Albany, a city on a hill with beautiful architecture. There were some ardent abolitionists here, and it had one of the main stations on the Underground Railroad on the route Frederick Douglass was connected to. Douglass named Stephen Myers, Lydia and Abigail Mott (who he entrusted with the education of his daughter Rosetta for a time) and William Topp in his autobiographies as some of the key figures here in the cause of the liberation of black people. But Douglass had some very unflattering things to say about Albany too: as he wrote in 1847, he observed a lot of racism here, especially in the wealthier families enriched directly or indirectly from slaveholding, and in the press. He was warmly welcomed by the congregation of the Baptist Church on State Street, but as of this time I can’t confirm its location: the current Baptist Church on State Street, Emmanuel, didn’t move there until 1869, and the Baptist church I found dating from his time was not on State St.

Tweddle Hall, inscribed ‘1754 Old Tweddle Hall’, from Albany Institute of History & Art Library

I wander the downtown area for a little while, glad to stretch my legs, admiring the grand city center buildings, soaring churches (mostly built in the mid to late 1880’s), old stone and brick row houses, and the lovely view east where the hill slopes down to the Hudson River. Then I head to my main destination, the site where Frederick Douglass spoke at the American Equal Rights Convention at Tweddle Hall, held November 20th and 21st, 1866. Tweddle Hall once stood at the northeast corner of State and Pearl, and originally built in 1860, it burned down, was rebuilt once in 1883, then replaced in 1927 by the Bank Building which now stands here.

Douglass had long been an ardent champion of the women’s rights movement; he had been the first to back Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s call for women’s suffrage at the Seneca Falls convention in 1848 (more on this story in an upcoming account).

But here in Albany, a serious split in the women’s rights movement began with the debate over the 15th Amendment. The American Equal Rights Association had formed earlier that year, on May 10th in New York City. The Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention reformed itself as the AERA, dedicated equally to black and female suffrage following the 14th Amendment, which for the first time specifically linked the word ‘male’ to the right to vote. While the 14th Amendment didn’t specifically guarantee the right to vote to all males, it did limit representation according to the number of adult males allowed to vote, overturning the hated 3/5ths compromise clause of the Constitution which granted representation, albeit reduced, to non-voting ‘persons bound to service for a number of years’, in other words, slaves.

Bank Building at northeast corner of State and S. Pearl, site of old Tweddle Hall

The proposed 15th Amendment, as written and as it was eventually passed, would guarantee the right to vote to all citizens regardless of ‘race, color, or previous condition of servitude’, leaving the ‘male’ link to voting from the 14th Amendment intact. Douglass’ biographer Phillip S. Foner describes Douglass’ position on the 15th Amendment as: ‘to women the ballot was desirable, to the Negro it was a matter of life and death.’ Douglass thought it was absolutely imperative that black people get the right to vote even if it meant putting aside other great political causes for the moment. Adding women’s right to vote to the 15th Amendment would make it so much more controversial that it surely wouldn’t pass. After all, it wasn’t only black men who were still suffering great oppression and failing to enjoy the rights the Civil War victory was supposed to have won them; black women suffered worst of all because they had no legally protected voters to represent them. To many in the women’s rights movement, this was an unpardonable breach of loyalty from the man who had been their dedicated champion from the beginning. But Douglass still supported the AERA, joined in their petitions, and even acted as a representative and as a Vice President over the years.

Unfortunately, as the political struggle for racial suffrage gained more traction than woman suffrage, some of the feminist political rhetoric took on a racist character, saying, for example, that suffrage for educated, civilized white women should take precedent over suffrage for uneducated, ‘degraded’ black people. Sadly, even his old friends and allies Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton stooped to this rhetoric, though in later years Stanton redeemed herself somewhat by warmly, and wittily, congratulating Douglass and Helen Pitts on their January 24th, 1884 marriage: ‘After all the terrible battles and political upheavals we have had in expurgating our constitutions of that odious adjective ‘white’ it is really remarkable that you of all men should have stooped to do it honor.’ Perhaps his good example of loyalty to her in later years, despite her earlier racist comments, helped her overcome the worst in her character that angry disappointment can tend to bring out even in the best of us.

Liberty St at Franklin, Troy NY, two blocks east of the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church historical marker site

I return to my car and drive about 15 minutes north along the Hudson River to Troy, another northern New York State former industrial town which has clearly suffered a long and steady decline. But it’s full of lovely old buildings and has an interesting history; for example, Elizabeth Cady Stanton attended Troy Female Seminary. It’s also a college town; when I stop for coffee and to do some research, I find myself among many college age students spending late Easter morning studying (though I suppose they’re on spring break, what good students!) and hanging out.

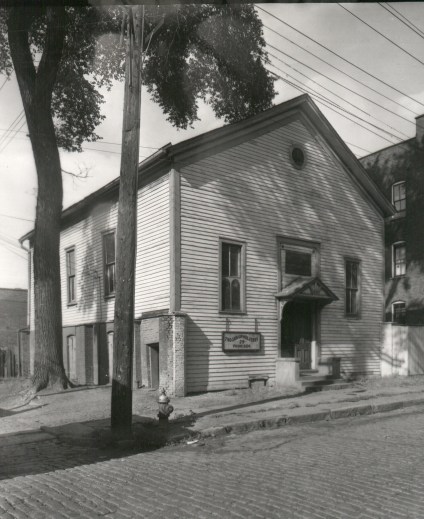

Liberty Street Presbyterian Church in a later incarnation as a laundry. This only known surviving photo is in the collection of the Rensselaer County Historical Society, Troy, NY

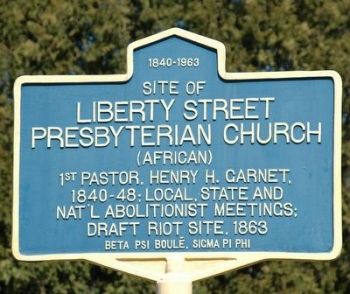

I’m headed for the site of Liberty Street Presbyterian Church, which Albany’s Times Union newspaper reports was on the corner of Liberty and Franklin Streets – which may not actually be the right street corner, as I discover when fact-checking and doing extended research for this account, more on that in a moment. The Liberty Street Church used to be a stop on the Underground Railroad, ran by pastor Henry Highland Garner from 1838 to 1848.

I’m looking for this site today because the 1847 National Colored Convention was held here, where the ultimately unsuccessful movement to start a national, unified Negro League movement began. According to John Cromwell in his 1914 book The Negro in American History, ‘…the very first article in the first number of [Douglass’ paper] the North Star published January, 1848, is an extended notice of the National Colored Convention held at the Liberty Street Church, Troy, New York, October 9th, 1847′. Nathan Johnson, who the Douglasses made their first home with in New Bedford, was president of the convention. Frederick Douglass was one of the Massachusetts delegates to this convention. He still espoused Garrisonian principles at the time (he changed his mind later), which, among other things, held that moral suasion and non-violent boycotting of politics were the most effective ways to end slavery. He called on his fellow black people everywhere to leave their churches if they were segregated or supportive of slavery in any way, and stressed the importance of education and self-improvement to stand as living testaments against the prejudices of white people. However, for a variety of reasons, it proved too difficult to unite the scattered, disenfranchised black community together into one unified movement. Those who were free shared the tactical and philosophical disagreements of white members of the abolitionist movement; those who were still enslaved or suffering the worst hardships of poverty, illiteracy, and other innumerable forms of intimidation and oppression found it difficult or impossible to participate.

So why might I be at the wrong street corner here at Liberty and Franklin? Because my additional research for this account prior to publication pulled up two locations for the old church, rather than the one I had initially pulled up. A couple of secondary and tertiary sources, which I find first and which guide my day’s search here, list the location as Liberty at Franklin: the newspaper, and this booklet for a historical project from 2008. I don’t yet have enough evidence now to prove definitively which is correct, though I believe one much is more likely. The crossing of Liberty and Franklin Streets is unmarked; Franklin is a narrow little street that runs between 2nd and 3rd, between the three story brick building and the two story white board one with the bay window. It’s a rather shabby little street corner now, the buildings here now don’t appear to be all that old.

Yet the historical marker for the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church is placed at Liberty and Church Streets, two blocks east of here. Oddly enough, the creators of the Spectres of Liberty project describe the site in their booklet as located on Liberty at Franklin, yet they hold their ‘Raising the Ghost of the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church‘, a super cool historical art event, at the marker site. Could it be that the street names have been changed or reassigned? A city map / atlas from 1845 reveals that the street names and locations are the same here today as they were then.

In case the historical marker is placed incorrectly (update: the Rensselaer County Historical Society assures me that the marker is at the correct site) and this does turn out to be the correct site, which corner of Liberty and Franklin could it have been on? Comparing the photo to the streets now, there’s one clue that might help me: the fire hydrant shown in the photo. There is no fire hydrant now, but there is a capped water supply pipe which could have supplied it; unless it’s torn up and moved, this would remain a permanent fixture. It’s in the sidewalk in front of the three story red brick apartment building on the northwest corner of the street. If this is the same water supply, that would place the church on that corner with its narrower pointy side facing on Franklin and its long side facing Liberty. However, when I look more closely at the photo I’m referring to (the only known surviving one, it’s in the Rensselaer Historical Society collection), the site where the historical marker is located, two blocks east at Liberty and Church looks more like the correct location, if the placement of the fire hydrant and the street pole are the same today.

So why include my story of possibly looking in the wrong place (which, as it turns out, I do)? Well, this travel series is the story of a journey, and journeys often include wrong turns, misreading of signs, incorrect maps, bad directions, and so forth. Each of these is a learning experience, and I hope you don’t mind that I take you along with me as I learn. As we’ve just seen, there are conflicting sources of information out there, and the lesson I learn here: triple-check all sources!

My last destination of the day is the site of Wieting Hall, at 111-119 W. Water Street in Syracuse, NY. The hall, which was first built in 1851, burned down in 1856 and was rebuilt as an opera house in 1857, burned and rebuilt yet again in 1881. Its builder and public-spirited owner Dr. John Wieting was a stoic yet tenacious man, responsible for its every incarnation. As you can see, what stands here now is not nearly so inspiring, in looks or in history.

On Nov 14th, 1861, Douglass was scheduled to deliver a speech on the Civil War and why the slaves needed to be freed en masse for the Union to win, one of his many appearances in Syracuse. Syracuse was another important stop on the underground railroad. However, as we’ve seen throughout this travel series, just because New York and other Northern states were free did not mean that all people here wanted black people to be armed, to enjoy civil rights, or even to be emancipated. Many in Syracuse were abolitionists and many others were not; racism was endemic in both of these groups.

According to Foner’s biography, an angry protest was planned: many townspeople were prepared to drive him and the other abolitionist speakers from the city. However, to his great credit, mayor Charles Andrews and Dr. Wieting refused to be intimidated, insisting that the talk take place as planned. They believed (as I agree all Americans should) that even unpopular speech should be protected speech, and their Syracuse was not to be a place where free speech could be squelched by threats. So 50 – 100 police were stationed (depending on the source) along with armed members of the Second Onondaga Regiment. When Douglass spoke, the crowd was well-behaved and respectful, be it because they actually did respect him and his right to speak, or because they were not allowed to be otherwise.

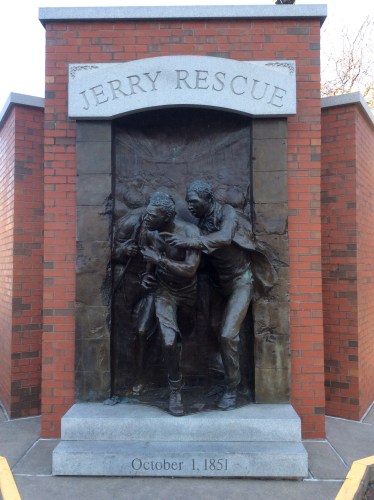

Clinton Square and Jerry Rescue Monument, at S. Clinton and W. Water Streets, Syracuse NY, with Wieting Hall site in the background

As I have plenty of daylight left, I wander through lovely Clinton Square, clearly a site in the process of restoration. The large rectangular concrete center used to be a part of the Erie Canal, a waterway route to the center of the city, and a place to ice skate when frozen over in winter (part if it is still filled with water and turned into a wintertime outdoor skating rink today!)

As I have plenty of daylight left, I wander through lovely Clinton Square, clearly a site in the process of restoration. The large rectangular concrete center used to be a part of the Erie Canal, a waterway route to the center of the city, and a place to ice skate when frozen over in winter (part if it is still filled with water and turned into a wintertime outdoor skating rink today!)

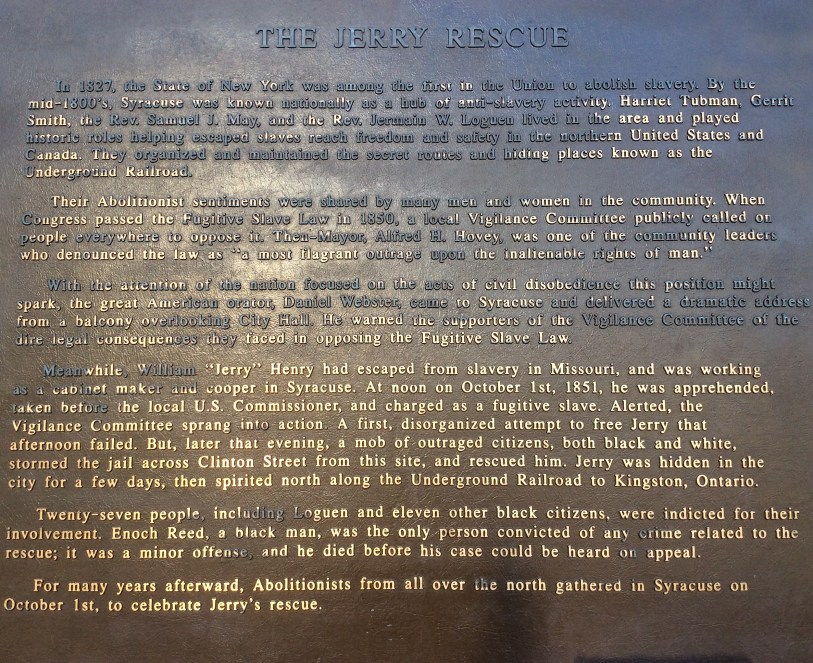

I discover a monument near the southwest corner of the square, erected in 2001 and dedicated to the October 1st, 1851 rescue of William ‘Jerry’ Henry. An escaped slave from Missouri, he was arrested as part of the effort to enforce the much-hated Fugitive Slave Act, enacted on September 18th, 1850. Many Northerners, abolitionist or not, thought it an intolerable intrusion on the legal autonomy of states and on freedom of conscience. Though the orator and statesman Daniel Webster (who, as you may remember from the second of my Lynn accounts, supported it as an acceptable compromise for preserving the Union) warned that the Fugitive Slave Act would be rigorously enforced here in Syracuse, it was vigorously defied on that October day. Attendees of the Liberty Party state convention (the party of Gerrit Smith, Douglass’ friend and mentor who we’ll learn more about soon) broke into the jail and freed Jerry, hid him in town for a few days, and smuggled him to Canada. This event would be long celebrated by abolitionists and champions of human rights, Douglass among them, as a triumph over oppression and in thanks to those who risked themselves to help a fellow human being in need.

So ends my tale of today’s adventures. I’m going to spend the night in a rented room in an old yellow house near beautiful Syracuse University, the most charming place I stay throughout the trip, with the exception of my new friends’ house near Baltimore and my old friends’ house in Rochester. Stay tuned for my continuing adventures following the life and ideas of Frederick Douglass!

So ends my tale of today’s adventures. I’m going to spend the night in a rented room in an old yellow house near beautiful Syracuse University, the most charming place I stay throughout the trip, with the exception of my new friends’ house near Baltimore and my old friends’ house in Rochester. Stay tuned for my continuing adventures following the life and ideas of Frederick Douglass!

~ Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and Inspiration:

‘Amendment XIV: Citizenship Rights, Equal Protection, Apportionment, Civil War Debt‘, Constitution Center website

‘Amendment XV: Right to Vote Not Denied by Race‘, Constitution Center website

‘American Equal Rights Association‘. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

Beauchamp, William Martin. Past and Present of Syracuse and Onondaga County, New York: From Prehistoric Times to the Beginning of 1908 (Volume 2). SJ Clarke Publishing Co: New York, 1908.

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, and The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series 2: Autobiographical Writings. 3 volumes. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999 (including a letter to Sydney H. Gay, dated Oct 4th 1847)

‘Courtesy of the Rensselaer County Historical Society: Rev. Henry Highland Garnet’. The Amistad Commission, New York Department of State website

Cromwell, John Wesley. The Negro in American History: Men and Women Eminent in the Evolution of the American of African Descent. J.F. Tapley Co: New York, 1914

Douglass, Frederick. Autobiographies (includes Narrative…, My Freedom and my Bondage, and Life and Times). With notes by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Volume compilation by Literary Classics of the United States. New York: Penguin Books, 1994.

‘Frederick Douglass Escapes Slavery, Becomes Leading Abolitionist‘, Onondaga Historical Association website

Foner, Philip S. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. 1-4. New York: International Publishers, 1950.

Garrison, William Lloyd. The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison, Volume IV: From Disunionism to the Brink of War, 1850-1860. Edited by Louis Ruchames

Hallaron, Amy. ‘Artist’s magic lives on in Troy‘, Times Union, Albany, Monday, January 16, 2012

‘Jerry Rescue‘. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

‘Jerry Rescue Monument‘, #44, Freethought Trail website

‘Liberty Street Presbyterian Church (African)’, Historical Marker Database (source of marker photos)

‘Lydia and Abigail Mott‘, Underground Railroad History website

McFeely, William. Frederick Douglass. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991.

‘Proceedings of the National Convention of Colored People and Their Friends; held in Troy, NY; on the 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th of October, 1847.’ Colored Conventions website, University of Delaware

Rittner, Don. Albany, Then & Now. Arcadia: Charleston SC, 2002

Robinson, Olivia, Josh MacPhee, and Dara Greenwald. Spectres of Liberty: The Raising of the Ghost of the Liberty Street Church. Website, booklet and video

‘Stephen Myers‘, Underground Railroad History website

‘Susan B. Anthony Boldly Writes the Speaker of the House Asking for a Public Endorsement of Women’s Suffrage‘, pamphlet for 1866 Convention and signed letter, RAAB collection website

‘Troy, N.Y., from actual survey‘ (map / atlas) by S.A. Beers, civl. engineer. Depicts: 1845

‘Upstate New York and the Women’s Rights Movement‘, University of Rochester / River Campus Libraries website

‘Wieting Opera House‘, #51, Freethought Trail website

Hypatia’s birthday is somewhere between 350 and 370 AD; a range of dates indicating great uncertainty, to be sure, but clear original sources this old are hard to come by, especially from a city as turbulent and violence-torn as the Alexandria of her day. The day of her death is better known, sometime in March of 415 AD. Since the latter date is more precise, we’ll break with our tradition here and remember Hypatia in the month of her tragic and violent death instead of on the date of her birth.

Hypatia’s birthday is somewhere between 350 and 370 AD; a range of dates indicating great uncertainty, to be sure, but clear original sources this old are hard to come by, especially from a city as turbulent and violence-torn as the Alexandria of her day. The day of her death is better known, sometime in March of 415 AD. Since the latter date is more precise, we’ll break with our tradition here and remember Hypatia in the month of her tragic and violent death instead of on the date of her birth.![Rosa Luxemburg, By unknown photographer around 1895-1900 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/rosa-luxemburg-by-unknown-photographer-around-1895-1900-public-domain-via-wikimedia-commons.jpg?w=323&h=383) Rosa Luxemburg, Mar 5 1871 – Jan 15 1919, is the great Marxist theorist, writer, economist, revolutionist, anti-war and anti-capital-punishment activist, and philosopher who was murdered during the German Revolution of 1918–1919.

Rosa Luxemburg, Mar 5 1871 – Jan 15 1919, is the great Marxist theorist, writer, economist, revolutionist, anti-war and anti-capital-punishment activist, and philosopher who was murdered during the German Revolution of 1918–1919. It’s been an especially busy few weeks for me: studying, researching, writing, planning for my upcoming traveling philosophy

It’s been an especially busy few weeks for me: studying, researching, writing, planning for my upcoming traveling philosophy

‘Beautiful’ has always been a battleground in feminist discussions of representation. While it may seem counterintuitive to argue that we should consider more women as beautiful while also arguing that a woman’s capabilities are worth more than her appearance, tackling the rigid definition of beautiful has been important for intersectional feminism. A traditionally beautiful woman is white; women of colour are more likely to be sexualised instead. A beautiful woman is also normally able-bodied. She usually does not appear to be economically below the middle-class, something that is subtly but pervasively inherent in our ideas of the ideal body shape (too slender for manual labour) and the current trend of tanning (demonstrating leisure time and disposable income). A beautiful woman often also has long hair, a delicate face, and big eyes; she is vulnerable, not strong. So renegotiating this limited meaning of beautiful is a powerful act. Great progress has made with it, which should be cause for optimism. However, recent redefinitions are more troubling than empowering.

‘Beautiful’ has always been a battleground in feminist discussions of representation. While it may seem counterintuitive to argue that we should consider more women as beautiful while also arguing that a woman’s capabilities are worth more than her appearance, tackling the rigid definition of beautiful has been important for intersectional feminism. A traditionally beautiful woman is white; women of colour are more likely to be sexualised instead. A beautiful woman is also normally able-bodied. She usually does not appear to be economically below the middle-class, something that is subtly but pervasively inherent in our ideas of the ideal body shape (too slender for manual labour) and the current trend of tanning (demonstrating leisure time and disposable income). A beautiful woman often also has long hair, a delicate face, and big eyes; she is vulnerable, not strong. So renegotiating this limited meaning of beautiful is a powerful act. Great progress has made with it, which should be cause for optimism. However, recent redefinitions are more troubling than empowering.