Flyer for Sanger Clinic, Brownsville, Brooklyn, image courtesy of the Margaret Sanger Papers Project

Tuesday, October 18th, 2016

I start the morning preparing my itinerary for the day as I fortify myself with coffee and the first half of a sandwich.

My first stop is also the furthest east I’ll go this trip, to the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn. I take the C train to the Rockaway station, head south on Saratoga, and wander around getting a feel for the neighborhood. It’s predominantly black, solidly working class, with lots of handsome old buildings, mostly well worn with peeling paint. I see lots of mothers and grandparents with strollers and very small children (it’s around noon during work hours), people taking smoke breaks in backdoors, and some very poor and homeless people. Reaching Pitkin’s busy sidewalk, I see shoppers, people going out for lunch, and shop and cafe proprietors in front doorways under brightly colored signs, and I hear many accents and many languages spoken, English, Spanish and French, and many others I don’t recognize. It reminds me of neighborhoods I frequent at home in Oakland. I turn north on Amboy Street, which runs north and south between Pitkin and E. New York Ave.

At 46 Amboy Street, just north of Pitkin, Margaret Sanger opened the United States’ first birth control clinic two days less than 100 years ago today, on Oct 16th, 1916. Though just a little late for the anniversary, I’m happy to be here at this historic place, humble as it now appears. The clinic was in the tall red brick building to the right of the tan one with the ‘diamond’ pattern on the upper center front of the façade. You’ll find a photo below that shows the clinic as it originally appeared, and here as well.

Sanger’s first birth control clinic, given address 46 Amboy St. One thing’s more or less the same: the little pale brick building with the crenelated top still stands next to where the clinic was, as you can see two photos down. The narrower red brick building against and to the left of the larger one, with a sign now identifying it as 42 Amboy, stands on the former clinic site.

Another view, angled more like the view in the photo below. The two red brick buildings appear not to be original unless they’ve been changed so much as to be unrecognizable. As you can see from the photo below, there was space between the original clinic building and the tan one, but not so for the current structure. The clapboard building beyond may be original.

Women and children sitting with baby carriages in front of the Sanger Clinic, with the white curtains in the windows. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Before opening this clinic, Sanger had trained and worked as a nurse for many years among the poorest and most oppressed Americans, the immigrant and minority working class and poor. Originally a Socialist radical, Sanger came to realize that Marxists, philanthropists, and charity workers alike were making the same essential mistake. Since they failed to identify the root cause of human misery in the slums, the crowded tenements, and the factory floors, all of their well-intended efforts to help were failing and sure to continue to fail. Sanger came to feel this way about her own nursing, which addressed the effects and not the cause, so she turned her efforts to where she believed she could do the most good: birth control activism.

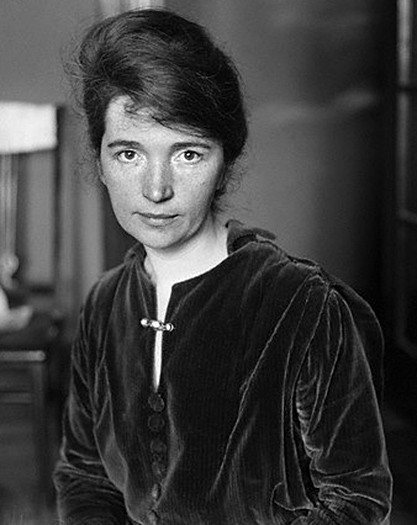

Margaret Sanger as a nursing student around 1900, by Boyce Photographer, White Plains, courtesy of the Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

As a nurse, Sanger cared for poor women broken down in health and mind by laboring all night and caring for children all day, often pregnant all the while, often miscarrying, and the infant mortality rates were very high. So were death rates for the mothers, be it from childbirth, diseases secondary to exhaustion and malnutrition, and worst of all, from self-inflicted abortions. The mothers who resorted to the latter were desperate: they had often already watched other children die, or suffer every day from hunger, or forced into the factories or other labor at a very young age in the struggle to survive.

Though there were plenty of organizations trying to help these families, governmental and charitable, they could not keep up since the need was so great and increasing every day. Industrialization, Sanger recognized, encouraged rapid population growth by the ever-increasing demand for more labor and more future customers. And the workers responded to the social pressure by producing more children in hopes that their offspring could help the family by going out to work. But those hopes were often in vain since the population growth always kept up with or surpassed the need for laborers, constantly driving down wages. And so the cycle continued: immiseration through near-starvation wages, families barely keeping up with the cost of feeding themselves if at all, and children deprived of an education and of health as factory and other hard work often left children stunted, with malformed and weak bones and muscles, and often injured by machinery and chemicals.

Sanger thought: instead of trying vainly to keep up with the spiraling misery caused by this cycle, why not get at the root of it? After all, as the old saying goes, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. If women were empowered to decide whether to have children, and only as many as their health and financial circumstances would allow, all this misery could be prevented in the first place since parents could adequately care for the children they did have, mother’s bodies would no longer be broken down by constant pregnancy, infants and mothers would more likely survive childbirth, overcrowding and its accompanying epidemics would be mitigated or even disappear, and a reduced labor force would force employers to compete for workers, driving wages up. And as we’ve seen over the decades, high population growth is strongly correlated with endemic poverty, high infant and mother mortality rates, women’s rights abuses, and high income inequality.

But people will never stop having sex, as Sanger pointed out. Sex is just too powerful a force in human nature. Our need for love, for affection, for physical pleasure and release, are too powerful to be squelched, and in fact, shouldn’t be. Love and the need for physical connection are positive things, indeed, two of the best things in human nature. Birth control, thought Sanger, was the answer.

I’ll be exploring Sanger’s ideas on these and other topics in more detail in upcoming essays, stay tuned. In the meantime, the Margaret Sanger Papers Project has a wealth of articles and original works by Sanger available online, and I’ve relied on them more than on any other single resource for my own project. (See below for the links). Thank you so much to the good people at the MSPP, I very much appreciate what you do!

Photobombed in Brownsville, Brooklyn, NY

Tree lined street with attractive row houses on Bergen Street, Brownsville, Brooklyn, NYC

Street scene at the Rockaway station entrance near the northern edge of the Brownsville neighborhood in Brooklyn, NY

Hipster Gourmet Deli in Brownsville, Brooklyn. I took this photo on the way to Amboy St, after my laughter subsided enough to take a picture.

I head back to the station, on the way stopping to photograph some scenes in the neighborhood, including an especially pretty row of houses on Bergen Street as a young man photobombs my pic with a laugh and a smile. On the train back, I eat the now rather smashed second half of my egg salad sandwich and write my notes. I transfer a couple of times and head north to Grand Central Station…. To be continued

Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and Inspiration:

Alter, Charlotte. ‘How Planned Parenthood Changed Everything‘. Time.com, Oct. 14, 2016

Chesler, Ellen. ‘Was Planned Parenthood’s Founder Racist?‘ Salon.com, Wed, Nov 2, 2011

‘Child Labor in U.S. History‘. From the Child Labor Public Education Project by the University of Iowa Labor Center

‘Demographics and Poverty‘, Center for Global Development.

Jacobs, Emma. ‘Margaret Sanger Clinic (former): the First Birth Control Clinic in the United States‘. From Places That Matter

Margaret Sanger Papers Project by New York University.

Regan, Margaret. ‘Margaret Sanger: Tucson’s Irish Rebel.‘ Tucson Weekly, Mar 11, 2004.

Sanger, Margaret. The Pivot of Civilization, 1922. Free online version courtesy of Project Gutenberg, 2008, 2013.

Sanger, Margaret. Woman and the New Race, 1920. Free online version courtesy of W. W. Norton & Company

I just listened to a podcast episode I had missed a year and a half or so ago, from my go-to podcast for discovering the gaps in my knowledge (of which there are so many! sigh) about Ancient Greek, Islamic, Medieval, and Indian philosophy from Peter Adamson’s

I just listened to a podcast episode I had missed a year and a half or so ago, from my go-to podcast for discovering the gaps in my knowledge (of which there are so many! sigh) about Ancient Greek, Islamic, Medieval, and Indian philosophy from Peter Adamson’s