Early on his career as an abolitionist speaker and activist, Frederick Douglass is a dedicated Garrisonian: anti-violence, anti-voting, anti-Union, and anti-Constitution.

Early on his career as an abolitionist speaker and activist, Frederick Douglass is a dedicated Garrisonian: anti-violence, anti-voting, anti-Union, and anti-Constitution.

In the early 1840’s, Douglass joins a revitalized abolitionist movement largely shaped by the views of William Lloyd Garrison. Since the early 1930’s, Garrison espouses a particular set of moral and political beliefs, radical for his time, which he promotes in his influential anti-slavery paper The Liberator. He believes in total non-violence, violence being a tactic of the slaveowners and their corrupt government protectors, not of good God-fearing people who have moral truth on their side. He believes that since voting implies that a government that legalizes slavery is legitimate, true abolitionists must abstain. He believes that the continued Union of the States, Abraham Lincoln’s sacred cause, was not only impossible, but undesirable: it involved the North, directly and indirectly, in the evil of slavery. Since the South was hell-bent on preserving that unnatural and therefore illegal institution, the South should go, and good riddance. And all of these are tied to Garrison’s view of the Constitution: it’s an ultimately pro-slavery, anti-human rights document, and therefore not worthy of obedience or respect.

For many years, Douglass fully agrees with Garrison. But over time, as a result of his conversations and debates with abolitionists who interpret the Constitution differently, and of his own study, experience, and thought in the first four years of publishing his own paper The North Star, Douglass changes his mind. By the early 1850’s, the abolitionist par excellence had come to disagree with Garrison, father of American radical abolitionism, and to agree with Lincoln, proponent of preserving the Union at all costs and of the gradual phasing out of slavery.

So how does Douglass come to make what seems such a counterintuitive change in his views on the Constitution and on the role of violence, voting, and the Union in bringing an end to slavery?

Some of the reasons for Douglass’ evolution are pragmatic; his pragmatist side becomes more pronounced with time and experience (more on this in another piece). For one, he comes to believe that violence is not only unavoidable at times, but sometimes necessary (more on this in another piece as well).

Douglass also becomes convinced that abstaining from politics is just suicide by degrees for the abolitionist movement, since it cedes political power to slaveowners and their supporters. Abstaining from voting in protest, as Garrison calls for, actually works against the project of obtaining greater political rights for black people. (As with celebrity comedian-guru Russell Brand’s anti-voting campaign today; the idea of abstaining from the vote in protest is neither new nor, in my opinion, any more effective now than it was then.) As Douglass points out, however motivated some people are to do the right thing by their fellow citizens, there will always be plenty of others motivated by greed, moral laziness in going along with the status quo, and the drive for power and domination over others. Political clout, gained through voting in those who represent their views, is one of the very few ways in which black people can finally obtain and protect their equal legal rights. And not only that: voting is one of the most practical yet powerful ways black people can demonstrate their full citizenship to those who might be inclined to doubt it. Other than getting an education and fighting in the war for emancipation, Douglass argues that it’s the most important way to undermine ugly stereotypes, prevalent in his day, of black people as lazy, uninformed, and fit only to have their lives run by others. (These stereotypes are, by the way, so ugly that it’s painful just to write them down, but confronting the ugliness head-on drives home the dire necessity of getting rid of them once and for all.)

But voting’s not enough to ensure that black people obtain the political power necessary to enhance and preserve their rights. For the abolitionist revolution to succeed, the Union must be preserved at all costs, and in the process, it must be recreated as the unified, true haven of freedom it’s meant to be. Douglass believes it’s the responsibility of the free states to liberate the enslaved people of the Southern states, and to extend and enforce guarantees of human rights for all inhabitants of all states.

Why? Because the Preamble of the Constitution tells us that’s what it’s for.

But how does Douglass justify this interpretation when it’s still a matter of such contention that he’s watching his country tear itself in two over it?

To understand the Constitution, it can help somewhat to consider the history that led to its creation and the ideas and intentions of those who wrote it; but to fully understand its true meaning and purpose, Douglass believes, we must always interpret all of its parts in the context of its preamble:

‘We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.’

The preamble is the key to any valid interpretation of the Constitution because it tells us, in plain, direct, and eloquent language, why the Constitution is written, who it’s written for, and who is bound to obey it. Any interpretation inconsistent with the Preamble reveals that either the Constitution itself is illogical, inconsistent and therefore invalid, or it shows that it’s the interpreter’s reasoning that’s illogical, inconsistent and therefore failing in understanding. Garrisonians agree with the first; Douglass agrees with the second.

So what to do with such parts of the Constitution as the three-fifths clause, which reads:

‘Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons‘?. (Art. I, Sec. 2, Cl 3.)

Doesn’t it imply that all those bound to service, which in Douglass’ time almost exclusively applies to black slaves, only count as three-fifths-person, and ergo, are not fully human? While Douglass grants that this clause is deeply problematic, he no longer agrees that it’s actually an endorsement of slavery.

There are two cases which can be argued when it comes to the effects of the three fifths clause: that it gives extra 3/5th’s representative powers to slaveowners, or that it takes away 2/5th’s; that point’s debatable. As Douglass points out, the clause actually appears to be a concession of a point that slaveowners didn’t really want to make but felt forced to if they wanted to increase their political power: that slaves are persons. If they’re not, it would make no more sense to include them at all for purposes of representation than it would to include cows, chickens, or farm implements. But even this grudging concession of personhood is conceivably debatable.

But while the effects of the three fifth clause may help indicate what use it’s been used for, they don’t tell us what it really means or what its true purpose is. So how do we successfully go about determining its meaning?

How about original intent? Since the expressed beliefs and opinions of the Constitution’s authors vary so widely on the matter of slavery, this won’t help us to decide the matter either. Douglass bases his original interpretation of the Constitution as a pro-slavery document on the basis of intent, but as we’ve seen, he changes his mind.

Well, then, how about strict constructionism? This won’t help us either. The terms used are so broad that it’s hard to tell what they literally and finally mean, or to prove outside of the historical context that they refer to the American brand of slavery at all. The three fifths clause never says anything about permanent bondage or race-based slavery. (In fact, the phrase ‘term of years’ seems to imply that there’s a beginning and end to the servitude in question that’s determined by something other than birth and death, but it doesn’t exclude the latter.)

So which interpretation of the three-fifths clause is most consistent with the preamble? Not the idea that those bound to service are anything other than persons or citizens, since the right to representation is only accorded to citizens, which, in turn, are necessarily persons. Nor is the idea that those bound to service are part-person or part-citizen: there’s nothing in the language of the clause nor of the rest of the Constitution that recognizes there’s such things as part-persons or part-citizens. Douglass points out that ‘…the Constitution knows of only two classes [of people]: Firstly, citizens, and secondly, aliens’. Constitutionally, all persons born in the United States are citizens by definition, and all others aliens; of course. the latter are still persons. So the ‘three-fifths’ clause can’t be referring to the completeness of individual persons; as we can see by the language itself, it specifically applies to the total number of persons for the purpose of apportionment only.

It’s clear, then, what the three-fifths clause says about persons and implies about citizens, but what does it really say about slavery?

It’s clear, then, what the three-fifths clause says about persons and implies about citizens, but what does it really say about slavery?

In a word, nothing. At least, not directly. As Douglass reminds us, the word ‘slave’ and its derivatives never appear in the Constitution at all. It does mention people ‘bound to service for a term of years’ but as we’ve already considered, this is unspecific, never mentions race, nor implies that bondage to servitude is ever anything other than limited.

There is one reading of the three fifths clause that I think is most consistent with the Preamble and with Douglass’ view of proper Constitutional interpretation. Given that the Constitution is concerned with Union, and Justice, and Tranquility, and the common defense, and the general Welfare, and Liberty, the three-fifths compromise was the best the founders could do at the time, given the intransigence of the slaveowners coupled with the young country’s need for their inclusion in the Union, to make the country large and strong enough to bring as much liberty as possible to as many people as possible. Bringing an end to slavery, Douglass believes, is the next necessary step for accomplishing the goals laid out in the Preamble as well as in the Declaration of Independence: to finally stamp out that liberty-destroying institution which had so undermined the general welfare, strength, and tranquility of the Union from its very beginning.

To return to the twin issues of personhood and citizenship in Douglass’ America: in a speech in 1854, Douglass says ‘In the State of New York where I live, I am a citizen and legal voter, and may therefore be presumed to be a citizen of the United States’. Just three short years later, in the infamous Scott vs. Sandford, a.k.a. the Dred Scott decision, the Supreme Court ruled that Douglass and all his fellow black people are not citizens at all. While Douglass explains in his speech’… [the] Constitution knows no man by the color of his skin’, the infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857 upended decades of common practice and legal precedent since the founding of the nation, where free black people throughout the United States had enjoyed legal, if not social, equality. However, as Douglass correctly observes, skin color is never mentioned in the Constitution as a precondition for citizenship, only place of birth and status of naturalization.

According to his biographer Philip Foner, Douglass becomes the most advanced and most informed thinker in Constitutional law, and the political and legal theory that informs it, than any of his fellow prominent abolitionists. Douglass believes, in the end, that the Garrisonian abolitionists are making the same mistake as the slaveowners: they fail to interpret the Constitution rightly, on its own terms and as a unified legal document unparalleled and unprecedented in its full establishment of human liberty. From the Garrisonians onward, those of us who likewise interpret the Constitution as protecting the rights of some without protecting others, or who likewise fail to understand its true significance, its true potential, and its true power to bring the blessings of liberty to all, just don’t get the Constitution.

*Listen to the podcast version here or on iTunes

Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~ Also published at Darrow, a forum for ideas and culture

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and Inspiration:

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, and The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series 2: Autobiographical Writings. 3 volumes. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, and The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series 2: Autobiographical Writings. 3 volumes. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999

Douglass, Frederick. Autobiographies, with notes by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Volume compilation by Literary Classics of the United States. New York: Penguin Books, 1994.

Douglass, Frederick. The Heroic Slave: A Cultural and Critical Edition. Eds Robert S. Levine, John Stauffer, and John McKivigan. Hew Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom: 1855 Edition with a new introduction.. Re-published 1969, New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Foner, Philip S. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. 1-4. New York: International Publishers, 1950.

Landmark Cases: Scott vs. Sandford (The Dred Scott Decision), A C-Span Original TV Series, 2015 http://landmarkcases.c-span.org/Case/2/Scott-V-Sandford

Antique firearms at the Edinburgh Royal Museum

Antique firearms at the Edinburgh Royal Museum

The

The  That’s because we’re still under the influence of a very old, even primal idea: that death is rendered not only glorious but a worthy goal if it’s for a cause. Nearly all ideologies and belief systems still prize their martyrs, and we see, worryingly, the resurgence of this idea in some parts of the world are leading to ever more deadly results. Martyrdom has long been such a potent symbol of belief and an effective recruitment tool that if there aren’t any genuine ones to hold up for emulation, it’s a sure bet some will be created. The Umpqua tragedy may be an example of this, of recasting the horrific murder of innocent people as a romantic tale of holy self-immolation in defiance of evil personified. The memory of the lives of the innocents who died there, and the heroism of those who risked themselves to protect others from harm, can become lost in the ideological rhetoric.

That’s because we’re still under the influence of a very old, even primal idea: that death is rendered not only glorious but a worthy goal if it’s for a cause. Nearly all ideologies and belief systems still prize their martyrs, and we see, worryingly, the resurgence of this idea in some parts of the world are leading to ever more deadly results. Martyrdom has long been such a potent symbol of belief and an effective recruitment tool that if there aren’t any genuine ones to hold up for emulation, it’s a sure bet some will be created. The Umpqua tragedy may be an example of this, of recasting the horrific murder of innocent people as a romantic tale of holy self-immolation in defiance of evil personified. The memory of the lives of the innocents who died there, and the heroism of those who risked themselves to protect others from harm, can become lost in the ideological rhetoric. Yet I am simultaneously wary of glorifying these cases of martyrdom for martyrdom’s sake, even when the circumstances of deaths such as these appear most moving, most noble, and most beautiful. That’s because I can’t forget, and I believe none of us can afford to forget, that what makes death or suffering count as martyrdom depends entirely on your frame of reference. My martyr may be your heretic; your martyr may be my traitor who deserved death; my martyr may be the holy warrior who attacked your corrupt and sinful country in the name of all that’s holy and your deadly foe it’s your patriotic duty to destroy. Martyrdom of this sort, understood as the ultimate sacrifice of the death-defying, uncompromising champion of the ultimate good, knows no side and every side. Every side claims their own, and every side who has martyrs to claim (creating them if necessary) treats them as their trump card, the ultimate demonstration of the rightness and superiority of their own beliefs. There’s Father Damien, and there are kamikaze pilots. There’s Quảng Đức, and there are suicide bombers. There’s Joan of Arc, and there are Crusaders, jihadists, those who carried out pogroms, and youth who still flock every day to join the ranks of ISIS and fight to deliver sacred territory from the hated infidels.

Yet I am simultaneously wary of glorifying these cases of martyrdom for martyrdom’s sake, even when the circumstances of deaths such as these appear most moving, most noble, and most beautiful. That’s because I can’t forget, and I believe none of us can afford to forget, that what makes death or suffering count as martyrdom depends entirely on your frame of reference. My martyr may be your heretic; your martyr may be my traitor who deserved death; my martyr may be the holy warrior who attacked your corrupt and sinful country in the name of all that’s holy and your deadly foe it’s your patriotic duty to destroy. Martyrdom of this sort, understood as the ultimate sacrifice of the death-defying, uncompromising champion of the ultimate good, knows no side and every side. Every side claims their own, and every side who has martyrs to claim (creating them if necessary) treats them as their trump card, the ultimate demonstration of the rightness and superiority of their own beliefs. There’s Father Damien, and there are kamikaze pilots. There’s Quảng Đức, and there are suicide bombers. There’s Joan of Arc, and there are Crusaders, jihadists, those who carried out pogroms, and youth who still flock every day to join the ranks of ISIS and fight to deliver sacred territory from the hated infidels. But here’s the problem: if it’s okay to sacrifice one person, even if that person is one’s own self, then it’s more than just a slippery slope to thinking it’s okay to sacrifice others. As we can see in such cases as kamikaze pilots, crusaders, holy warriors, and suicide bombers, the glorification of martyrdom has always had the unfortunate tendency to inspire willingness to sacrifice others along with ourselves. After all, if it’s good to sacrifice one person for the greater good, isn’t it at least as good or even better to sacrifice more people? But self-inflicted martyrdom which simultaneously kills others is generally not driven by this sort of calculation, of each side just upping the ante. When we consider martyrdom, we must also consider the ideologies and belief systems that inspire or at least allow for it. And nearly all not only involve a belief in an afterlife, they believe this world is merely a proving ground for that afterlife, so death counts for little in comparison to eternity. Furthermore, most ideologies and faiths who glorify martyrdom base their beliefs on sacred books in which holy war and violent destruction of the nonbeliever, the godless, the idolator, and the infidel is celebrated as much or even more than personal martyrdom. In the end, we end up with the same old world full of mutually hostile martyr/holy warrior belief systems that have led to centuries of violent religious and ideological conflict and ethnic cleansing.

But here’s the problem: if it’s okay to sacrifice one person, even if that person is one’s own self, then it’s more than just a slippery slope to thinking it’s okay to sacrifice others. As we can see in such cases as kamikaze pilots, crusaders, holy warriors, and suicide bombers, the glorification of martyrdom has always had the unfortunate tendency to inspire willingness to sacrifice others along with ourselves. After all, if it’s good to sacrifice one person for the greater good, isn’t it at least as good or even better to sacrifice more people? But self-inflicted martyrdom which simultaneously kills others is generally not driven by this sort of calculation, of each side just upping the ante. When we consider martyrdom, we must also consider the ideologies and belief systems that inspire or at least allow for it. And nearly all not only involve a belief in an afterlife, they believe this world is merely a proving ground for that afterlife, so death counts for little in comparison to eternity. Furthermore, most ideologies and faiths who glorify martyrdom base their beliefs on sacred books in which holy war and violent destruction of the nonbeliever, the godless, the idolator, and the infidel is celebrated as much or even more than personal martyrdom. In the end, we end up with the same old world full of mutually hostile martyr/holy warrior belief systems that have led to centuries of violent religious and ideological conflict and ethnic cleansing. And who’s to say who’s right? Which religion, which ideology has the correct view of martyrdom? Which, if any, can be demonstrated to inspire true martyrdom, to the exclusion of others? Bertrand Russell, philosopher and ardent pacifist, is often quoted as saying ‘I would never die for my beliefs because I might be wrong’. Many have described this as cynical or revealing a weakness of character, an inability to form convictions. I think a more fair and charitable interpretation is that Russell believed everyone should practice proper epistemic humility. Especially when it comes to such a momentous question as preserving human life, our own and others: we should do so whenever possible, since whatever our other beliefs, we can all readily demonstrate, whatever our other beliefs, that other human beings suffer grief when we die and that we can surely help others when we’re around to do so. It’s far more difficult to demonstrate, for example, that God likes it even better when we die in his name or that we can help those on earth from beyond the grave, as believers in intercessory prayer or spiritualists hold. Better all around, when it comes to our safety as well as our chances of not believing in things that are terribly wrong, when we’re accountable to one another for the larger consequences of our beliefs.

And who’s to say who’s right? Which religion, which ideology has the correct view of martyrdom? Which, if any, can be demonstrated to inspire true martyrdom, to the exclusion of others? Bertrand Russell, philosopher and ardent pacifist, is often quoted as saying ‘I would never die for my beliefs because I might be wrong’. Many have described this as cynical or revealing a weakness of character, an inability to form convictions. I think a more fair and charitable interpretation is that Russell believed everyone should practice proper epistemic humility. Especially when it comes to such a momentous question as preserving human life, our own and others: we should do so whenever possible, since whatever our other beliefs, we can all readily demonstrate, whatever our other beliefs, that other human beings suffer grief when we die and that we can surely help others when we’re around to do so. It’s far more difficult to demonstrate, for example, that God likes it even better when we die in his name or that we can help those on earth from beyond the grave, as believers in intercessory prayer or spiritualists hold. Better all around, when it comes to our safety as well as our chances of not believing in things that are terribly wrong, when we’re accountable to one another for the larger consequences of our beliefs. In a world where religiously-, politically-, and ideologically-motivated terrorism and mass shootings are again on the rise, we need to let go of our old cherished ideal of martyrdom as the ultimate holy and noble act. If we want to instill in ourselves and others the value that all lives matter, the glorification of any kind of martyrdom appears as toxic to this as the old belief in the curative powers of bleeding and purging was to health. This seems like a call for rejecting our long-loved heroes, our Joans and Quảngs and Damiens, but I don’t believe it is. We have a robust capacity for understanding that context matters, and just as we can believe George Washington’s doctors did their best to cure him the only (turns out wrong) way they knew how, we can simultaneously revere the courage and conviction of martyrs of the past while believing that in the age of universal human rights and ethics of care, martyrdom is the wrong way to go and should not be glorified, praised, or used as evidence of the superiority of our own beliefs over others.

In a world where religiously-, politically-, and ideologically-motivated terrorism and mass shootings are again on the rise, we need to let go of our old cherished ideal of martyrdom as the ultimate holy and noble act. If we want to instill in ourselves and others the value that all lives matter, the glorification of any kind of martyrdom appears as toxic to this as the old belief in the curative powers of bleeding and purging was to health. This seems like a call for rejecting our long-loved heroes, our Joans and Quảngs and Damiens, but I don’t believe it is. We have a robust capacity for understanding that context matters, and just as we can believe George Washington’s doctors did their best to cure him the only (turns out wrong) way they knew how, we can simultaneously revere the courage and conviction of martyrs of the past while believing that in the age of universal human rights and ethics of care, martyrdom is the wrong way to go and should not be glorified, praised, or used as evidence of the superiority of our own beliefs over others.

In a letter to a friend recently, I was reminiscing about my years working in a salvage and recycling yard. It was founded by an idealistic and action-oriented sociologist right near the edge of the local dump’s garbage pit, now grown to a fairly large operation that employs about forty people. I loved and miss the work: it was dirty, physically demanding, creative, and full of the thrill of treasure hunting, as founder Dan Knapp, my fellow salvagers, and I made all manner of discarded things available for use again. We diverted truckloads upon truckloads of things from the landfill every day, and dug among boxes and bags of trash and pulled out everything recyclable or reusable we could find. We rescued all manner of interesting artifacts; one box of ephemera we sold

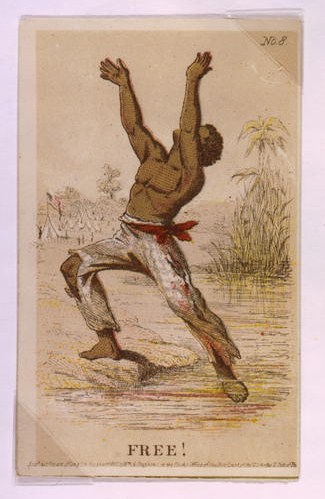

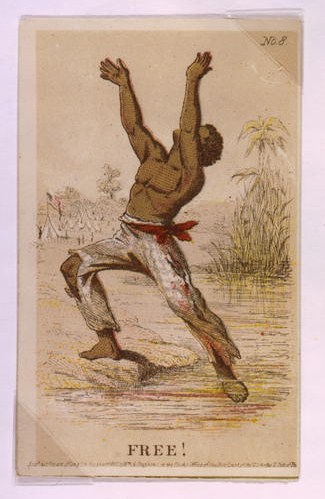

In a letter to a friend recently, I was reminiscing about my years working in a salvage and recycling yard. It was founded by an idealistic and action-oriented sociologist right near the edge of the local dump’s garbage pit, now grown to a fairly large operation that employs about forty people. I loved and miss the work: it was dirty, physically demanding, creative, and full of the thrill of treasure hunting, as founder Dan Knapp, my fellow salvagers, and I made all manner of discarded things available for use again. We diverted truckloads upon truckloads of things from the landfill every day, and dug among boxes and bags of trash and pulled out everything recyclable or reusable we could find. We rescued all manner of interesting artifacts; one box of ephemera we sold

It’s been an especially busy few weeks for me: studying, researching, writing, planning for my upcoming traveling philosophy

It’s been an especially busy few weeks for me: studying, researching, writing, planning for my upcoming traveling philosophy  There’s a lot of anti-Muslim sentiment in this country and in many other parts of the world these days: if you don’t look too deeply into history, or at how denominations of Islam differ from each other, or what the political situations are the Muslim world right now, it’s not hard to see why. The bare fact is: the majority of ideologically driven terrorists in the world today are Muslim.

There’s a lot of anti-Muslim sentiment in this country and in many other parts of the world these days: if you don’t look too deeply into history, or at how denominations of Islam differ from each other, or what the political situations are the Muslim world right now, it’s not hard to see why. The bare fact is: the majority of ideologically driven terrorists in the world today are Muslim.

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, and The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series 2: Autobiographical Writings. 3 volumes. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999

Blassingame, J. (Ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. 4 volumes, and The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series 2: Autobiographical Writings. 3 volumes. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979-1999