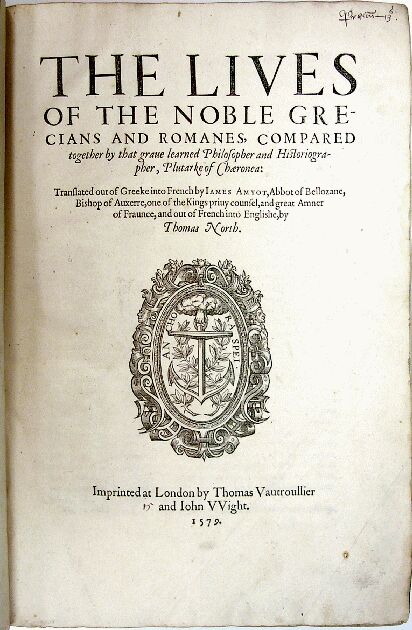

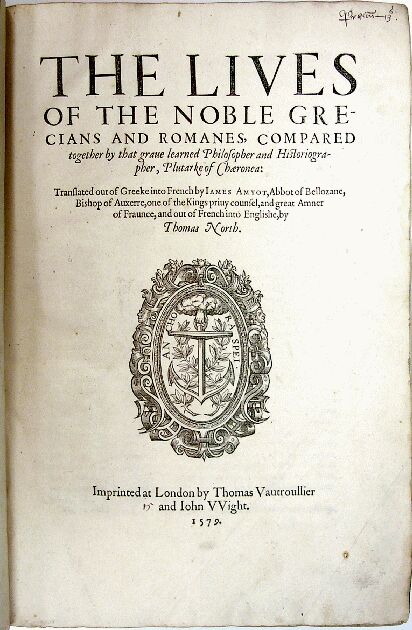

Title page of Thomas North’s translation of Plutarch’s Lives, 1579, first edition

Sunday, June 11th, 2017

I’ve been planning to read the whole of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans for some time. I’ve also been longing for a really good stretch of the legs, especially after this last week of office work and a Saturday selling off more of my belongings in preparation for my move to Scotland. (Sorting and selling off most of the artifacts of my life and of my twenty-plus years of small business ownership has been a tedious process. If the ashes would turn into dollars to fund my education and travel, I’d gladly set it all on fire at this point and be done with it.)

It occurred to me yesterday that I could do both my hiking and my reading on my free day tomorrow! So I downloaded Lives from LibriVox onto my little portable audio player and plotted a good long Bay Area Ridge Trail hike similar to one I did two years ago. This time, my start in Anthony Chabot Regional Park would be from Lake Chabot Golf Course on the lower east end of the park since I can get there more easily without my car than to other trailheads down there. The hike is about 28 miles long, with about 4,200 feet of climbing and about the same descending all told, and goes from Oakland north to San Pablo. The hike goes through 8 regional parks and nature preserves: Anthony Chabot Regional Park, Redwood Regional Park, Huckleberry Botanic Regional Preserve, Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve, Siesta Valley Recreation Area, Tilden Regional Park, Tilden Nature Area, and Wildcat Canyon Regional Park. I’ll hike through winding creek canyons, oak forests, redwood forests, eucalyptus groves, an ancient volcanic site, and chaparral.

This morning, I walk north and east from Lake Chabot Golf Course shortly after seven thirty, then enter Chabot Regional at the end of Grass Valley Road in south Oakland, near the San Leandro and Castro Valley borders. I take Jackson Grade east and down to Brandon Trail, where I turn left just before the sweet little stone bridge that crosses Grass Valley Creek. I head north along the east bank of the creek.

Stone Bridge over Grass Valley Creek, at Jackson Grade and Brandon Trail, Anthony Chabot Regional Park, Oakland

Plutarch’s first story tells of Theseus, founder of Athens, who rampaged around Ancient Greece like the personification of Dante’s nine circles of hell, punishing wrongdoers by inflicting on them the same species of violence they’d wreaked on others. He was quite bloodthirsty in his righteousness, slaying men and animals alike in the goriest ways possible, parading their carcasses around as warnings to the would-be wicked. But hey, all in the name of justice and glory, right? After all, according to the honor code of Theseus’ culture, a man was nothing until he’d proved himself by feats of courage, usually involving slaying an enemy. But in pitting his strength only against those who harmed and oppressed others, Theseus can be thought of as a sort of combination of Robin Hood and Dexter, the fictional serial killer/forensic scientist who directs his blood lust only against other serial killers he’s proven guilty by means of his science. But like Dexter, Theseus’ life of exploits didn’t end well, though for very different reasons. As well as a brave one, Theseus was a vainglorious and randy man, and his reputation as a hero was undermined over time by his increasing rapaciousness, concupiscence, and mistreatment of women, especially by the abduction and rape of Helen of Troy.

Looking back at Macdonald Trail, across Grass Valley Creek, from Big Bear Staging Area, where I cross Redwood Road to enter Redwood Regional Park

It’s a beautiful morning here in Chabot, sunny and a little cool. The blustering winds of yesterday have given way to occasional gentle breezes. The poppies are still closed. The cottontails hop across the trail: they emerge in the cool of the morning and the early evening and are as plentiful as, well, rabbits. Tall thistles are in bloom, and wild mustard, and lupine, and tall dandelions, and a flower that looks like Queen Anne’s lace, and sweet-smelling cones of pale pink flowers on a species of tree I can’t name. There’s a plentiful grass tipped with seed pods that arrange themselves in structures that look like rattlesnake tails, bending the stems over with their weight.

My itchy eyes and runny nose tell me I forgot to take my allergy medicine this morning in my haste to start early. It’ll be a sneezy, watery day as well as an educational one for my head.

Entering Redwood Regional Park across Redwood Road from Big Bear Staging Area of Anthony Chabot Regional Park

I cross Redwood Road and Grass Valley Creek by a little bridge into Redwood Regional Park. As I cross the bridge, Plutarch has begun to tell the life of his second hero, Romulus, founder of Rome and for whom it was named, and some stories of his twin brother Remus. Plutarch introduces this account with a long series of summaries of alternate foundation tales from popular lore. He assigns various levels of credibility to each since each story appears more fantastic than the one before, but still includes them so as to remain faithful to the pledge he makes at the beginning of his Lives to be as historically accurate as possible. But I think he settles on this Romulus story because it fits with his chosen literary construction, and not so much because it’s any less implausible. Plutarch is aware of the latter, so he seeks to gain the confidence of his readers with the admonition ‘we should not be incredulous when we see what a poet fortune sometimes is.’ As you likely guessed already, Plutarch alternates his accounts of great Greeks and Romans in pairs, chosen because they play corollary roles in the history and mythology of each culture. Theseus was the storied founder of Athens, Romulus of Rome.

Commemorative marker on Golden Spike Trail running north along Grass Valley Creek, Redwood Regional Park

Romulus and Remus, for one of many possible reasons of court intrigue that Plutarch offers in explanation, were cast out as babies from their royal family, set afloat in a trough on the river like the biblical Moses, and left to the mercies of the rushing water and the wild animals, their flesh to become food for the birds. Instead, they were suckled by a wolf and fed by birds, especially woodpeckers, made sacred to the Romans by this kind act. The twins grew strong, bold, and handsome, conquerors of men and lovers of women. Now grown men, they overthrew one usurping and unjust tyrant, and instead of taking control themselves, they handed the city over to the rightful ruler. The only power they chose to wield was over a city they would found themselves.

A little later on in the story, I’m struck by Plutarch’s justification of the legendary rape of the Sabine women by the newly made Romans, a story immortalized countless times in art over the centuries. The commoners who left home to follow Romulus and Remus, out of admiration for their courage and just dealings, after a time sought to populate their new city by abducting women from the neighboring Sabine people. Plutarch shrugs his shoulders and writes, well, this violent act of mass rape and coerced marriage wasn’t really an act of barbarity or cruelty, but rather of necessity, since there weren’t enough women around actually consenting to marry them. And anyway, once the men had raped and impregnated and wed them, they were nice to the ladies thereafter. Yikes. As James Brown would observe, that was a man’s world, and the first Roman men of legend agreed, in the worst possible fashion, that it ain’t nothin’ without a woman or a girl.

The Abduction of the Sabine Women by Nicolas Poussin, 1634–1635, Metropolitan Museum of Art, public domain via W.C.

And besides, Plutarch continues in his attempts at exoneration, the budding new city openly offered sanctuary to all escaped slaves, to fugitives from the law, and to all other unhappy and dispossessed people willing to become members of the new society they were building from scratch. It’s interesting that Rome, which Plutarch praises as the pinnacle of justice, order, and noble accomplishment, is, as he tells it, also the product of abductors, rapists, and violent criminals as well as of enterprising seekers of liberty and a better life.

Redwood Bowl in Redwood Regional Park, a welcome water stop and bathroom break

Plutarch also tells of a certain philosopher and mathematician assigned many centuries later to fix the date of Romulus’ birth, based on accounts of an eclipse that occurred around that time and on other events in his life ‘just as solutions of geometrical problems are derived.’ Plutarch goes on to consider the validity of the idea that the lives of human beings could similarly be described and even predicted so long as the astrologer had all of the relevant celestial information about the positions of the heavenly bodies. He describes the controversy over that theory in terms not entirely dissimilar to naturalist determinists and their ideological opponents today.

Panoramic view of Redwood Regional Park from West Ridge Trail

Following Plutarch’s account of a later attack of the Sabines on Rome, since the former didn’t take kindly to the earlier predations of the latter, and the subsequent betrayal of the city to its enemies, Plutarch makes another interesting observation. Julius Caesar once said that he loved treachery but hated traitors, just as all people hate and despise providers of things they need but are ashamed of needing. Plutarch offers these quotes and incidents as emblematic of the ways of the world. And we’ve seen this sort of this countless times through history following Plutarch. Christians of Europe, for hundreds of years, justified their persecutions of the Jews partly on account of usury. The objects of their hate were making a living providing the very loans the Christians relied on to build their wealth, but when it became more expedient to rob and kill their creditors from time to time, all bets were off. Slaveholders of the American South similarly despised and persecuted the very people who made their wealth and comfort possible, justifying their oppression on account of supposed inferiority as they quashed any attempt by their slaves to better themselves through education and work on their own behalf. And so on, and so on…

Amy and a stand of Matilija poppies at Skyline Gate of Redwood Regional Park. Two parks down, six to go!

Tiny pink buds seem to float among the starry leaves along Skyline Trail in lush Huckleberry Botanic Regional Preserve

After a good long climb, West Ridge Trail curves around to the right to become East Ridge Trail; after a short walk along this trail, I turn left at the Bay Area Ridge Trail, leaving Redwood Regional via the connector path, and crossing Pinehurst Rd., I enter beautiful Huckleberry Botanic Regional Preserve.

Skyline Trail, which winds through beautiful and lush Huckleberry, and which runs along Round Top Creek through much of Sibley Volcanic, the next park, is thickly lined with poison oak, in some places hard to avoid. The rainy winter and spring caused them to flourish, but I walk in trepidation. I had to pick my way with special care on Golden Spike Trail in Redwood, since that trail is very, very narrow, almost overgrown in places. The wildflowers that grow plentifully in spring, such as hound’s tongue, blue-eyed grass, and California buttercups, are nearly gone. Now, there’s lots of sticky monkey flower, Ithuriel’s Spear, blue dicks, mule ears, and many other flowers, as well as those I named earlier.

Plutarch wraps up this part of his Lives with a reflection on the sudden and unexplained death of Romulus and the deaths of other heroes and kings under similarly suspicious circumstances. He takes this opportunity to share his beliefs about death and the soul, and quotes the ancient philosopher Heraclitus: ‘A dry soul is best’. This quote is oftentimes interpreted as a comment on the immorality of drinking, but Plutarch interprets it as being about a soul burdened by its connection to a fleshly body, full of blood and fluids associated with the basest of needs and desires and with illness: saliva, semen, urine, phlegm, and so on. He believes that souls are defiled so long as they remain arrayed in flesh, and become pure and holy only when completely divorced from the body. Plutarch goes on to say that he believes all great and virtuous men, purified of flesh, go on to become immortal heroes, then demigods, then gods. In his ideas about the purity of souls, the corruptions of the flesh, and that at least some human beings have the potential to become gods eventually, Plutarch is in agreement with the Christians in some ways, and with the Mormons in others.

Panoramic view looking over Huckleberry Botanic Regional Preserve, from an outlook above the steepest part of the climb out of the creek canyon

Lycurgus, illustration from William C. Morey’s Outlines of Greek History, Chicago, American Book Company, 1903

Then comes the story of Lycurgus the Lawgiver, the legendary Greek king who instituted the rigid militarist social system that remains emblematic of ancient Sparta to this day. Plutarch tells how a preceding king, Eurytion, had relaxed the severity of his monarchic rule in order to win the favor of his people. But the people, over time, ‘grew bold’ and rose up against attempts by subsequent rulers to strengthen their own power. Earlier, in his reflections on the comparative merits and demerits in the characters of Theseus and Romulus, he praised Theseus’ preference for increasingly democratic rule over Romulus’ evolution (or, devolution) into tyranny. Plutarch attributes excesses in favor of democracy to a generous and kindly spirit, and excesses of tyranny to pride and selfishness. Yet when he opens his story of Lycurgus with the destabilization of society following increased democratization, he seems to contradict himself when he earlier associates virtue with democracy and vices with tyranny, until we remember that in the first case, he’s speaking of the characters of individuals, and in the second case, he’s pointing out that democracy is not always the best answer for society at large. John Adams and Alexander Hamilton would sympathize with Plutarch here, while Thomas Jefferson would side with the people. I think Jefferson would point out, as he does following the pandemonium following the first French Revolution, that excesses are bound to happen in any struggle against tyranny. As they settle into their newly won liberty, however, people’s better natures, which predominate in the souls of all free and educated people, have the opportunity and the desire to create a just and happy society.

When Lycurgus took power, however, he perceived a society that had become ‘effeminate’ (negative term in those days), weak, selfish, and corrupt through addiction to sensual pleasures and the small-souled desire to amass personal wealth. So Lycurgus set out to re-craft his Sparta into an ideal society. One of his first reforms was the redistribution of land. He observed that most of the land was held by a few, leaving much of it undeveloped and unfarmed, while many more people were poor and unemployed. He convinced the landowners, as Plutarch tells it, to give up some of their land, which he thus distributed evenly among the citizens. He then instituted more practices designed to reduce useless luxury, overeating, and other forms of excess which caused both poor health in the individual and envy between individuals. In fact, he convinced his subjects to perceive the appearance of wealth as a defect, something to be abhorred as a sign of petty, self-indulgent weakness. Lycurgus’ system of social engineering, instituted by both persuasion and force, was not entirely welcome to the Spartans, but Plutarch heartily approves.

Looking back on shady Skyline Trail in Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve, which runs along Round Top Creek

Looking back on Sibley’s volcanic formations rising above the trees, from Fish Ranch Road. Please excuse the shadow in the corner, I didn’t notice the cover on my tablet had been knocked askew in my backpack, slightly obscuring the camera lens.

Skyline Bay Area Ridge Trail crossing on Fish Ranch Road, looking north at Siesta Valley Recreation Area

Intensely blue starry flowers along Bay Area Ridge Trail through Siesta Valley Recreation Area

Yet Spartan society, so rigidly designed by Lycurgus according to his ideas about virtue and utility, was not egalitarian in the sense that we’d understand the term. It was an intensely aristocratic society centered around a warrior elite, with an equality enforced only among that class. Wives were obtained by force, children were removed from the care of their parents at the will of the state, and deformed and sickly babies were put out to die of exposure. And as Plutarch so casually mentions, all of this equality of the ‘best’ in society, crafted by both positive and negative eugenics practices, and their strict training in virtue, sport, and war, was made possible by the slave labor of the subjugated helots. Plutarch does not seem the least distressed by this; in fact, he seems to accept this as a most natural state of affairs. He does regret that the helots were often treated harshly, even murderously, by their Spartan enslavers, but he insists that this institutional cruelty came only after Lycurgus’ rule by subsequent kings of lesser moral character.

Plutarch tells us next about Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome. Numa was a was held in high regard by the people because he was humble, contemplative, lived simply, scorned money-making, and spent his time in study and in service to his people. After the death of Romulus, he was widely accepted as the best candidate to succeed to the throne, endorsed by Romans and Sabines alike. The original Romans and the Sabines, who had cohabited Rome in an uneasy, fractured peace, wanted a ruler who would deal as justly with one group as another. The senators who had taken over the government didn’t have the trust of the people: many believed they were corrupt and that they had, in fact, assassinated Romulus. So they decided to elect a king to keep watch over the Senate and to lead the inhabitants of Rome as one united people.

Hillside covered with sticky monkey flower in Siesta Valley Recreation Area

Beautifully patterned redwood stump near the meeting of Siesta Valley Recreation Area and Tilden Regional Park

So at 40 years old, having lived an already long life of virtue, Numa settled with reluctance, feigned or not, onto the throne. According to Numa, wielding power was not his dream: he preferred a life of mostly solitary contemplation. Plutarch, however, rather seems to describe the actions of a man secretly rejoicing in the power offered to him while coyly disguising his satisfaction. In any case, Numa was a philosophical man who believed strongly in social justice and had some earlier experience as an adjudicator. So he immediately got to work. He banished the huge retinue of servants the Romulus had gathered around him in his tyrannical old age. He instituted many reforms to gain the trust of the people and to promote peace, especially between the Sabines and the original Romans. The factional and ethnic conflict that had long plagued Rome threatened its stability and made it vulnerable to attack. So he found one inventive and one practical way to solve these problems: involuntary social mixing and censorship. He assigned individual members of differing groups to shared trades that would force interaction and cooperation that otherwise wouldn’t happen, and he forbade any references to belonging to particular cultural or ethnic groups. From now on, decreed Numa, all of his subjects were simply Roman.

I’m reminded here of a very interesting article I read about Singapore a couple of years ago, a nation which addressed a similar problem in a similar way. Singapore is a densely populated, tiny island country made up largely of immigrant workers and their descendants, of very diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds. Singapore maintains its relatively low level of interracial and interreligious conflict by assigning ethnic and religious quotas to all neighborhoods. By forcing its citizens to live, work, go to school, shop, and in every other way share their public lives by people of diverse backgrounds, Singapore hopes that everyone will be so accustomed to diversity that they’ll accept it as a matter of course. Or, even better, a matter of pride and celebration. I suspect that Singapore’s two Prime Ministers may have read Plutarch’s Lives.

Panoramic view facing east from Seaview Trail, Tilden Regional Park, with Briones Reservoir and Mt Diablo

San Francisco, Treasure Island, Alcatraz, the Golden Gate Bridge, the Marin Headlands, Angel Island, and the Bay as seen looking west from the Seaview Trail in Tilden Regional Park

Statuette of a running girl, Spartan, about 520 BCE, British Museum. Note her bare breast, short skirt, and saucily exposed thigh. I think Lycurgus would secretly like this sculpture very much

Plutarch admires both Lycurgus and Numa. Like Lycurgus, Numa instituted his vision of a virtuous society through strict social regulation. They both believed it was the government’s job to protect the people from enemies within as well as without. Therefore, both instituted strict behavior codes for citizens as well as ways to promote peace and defend their people from military attack. Plutarch, who values virtue over liberty, generally approves of their social engineering systems but has a few problems with both as well.

For example, he’s shocked by Spartan women mingling freely with young men in public, wearing short tunics that left their thighs visible, permitted by the Lycurgian code. Plutarch seems sympathetic to or at least intellectually satisfied with Lycurgus’ theories about the power of sex to unite sympathies and strengthen social bonds. But Plutarch really dwells quite a bit on the topic of publicly bared Spartan female thighs with so much delighted horror that methinks he doth protest too much. Plutarch doesn’t, however, seem to pass judgment on the sexual practices of Spartans, which include lover- and spouse-sharing, homosexual sex and erotic play, child lovers, and coercive sex, all of which have been mostly censured and banned by law and religion since Plutarch’s time.

He approves of Numa’s restrictions on women, such as banning them from appearing and speaking in public, and of the policy of marrying them off very, very young so their husbands can instill complete obedience in them as they grow up. Yet Plutarch criticizes some of Numa’s policies when it comes to punishing crimes against women, finding them merely arbitrary in some cases and not punitive enough in others. He believes Numa could have done more to protect women’s virtue in this area. In matters of gender and sexuality generally, it’s not sexual practices that provoke Plutarch’s moralizing, as it was for so many governments and religions succeeding him throughout the centuries. He seems bothered only by practices which run contrary to his own conception of the primary feminine virtues, which, according to Plutarch and Numa, are modesty and obedience.

Wildcat Canyon, panoramic view from the entrance to the park from Tilden Nature Area looking northeast

As I enter Wildcat Canyon Regional Park from Tilden Nature Area, Plutarch has recently introduced me to the ancient Athenian lawmaker, poet, and ruler Solon. I’ve heard of him, but remember little. I’m about 23 miles in with another five or so to go. My feet have been very sore for the last five miles already and I’m limping. But I’m happy, and in a dreamy, almost hypnotized state at times from my regular, ceaseless footfalls. I discovered it’s no good to stop: as soon as I let my feet rest, the blood rushes into them and then it’s more painful to start again than it was to keep them a little numbed by constant use. Besides, I need to meet my ride home, and I’m behind time since I had paused so often to take pictures and slowed down so many times to tap out my reading notes.

In Wildcat Canyon Regional Park, view looking northwest from Nimitz Way

In Wildcat Canyon Regional Park, looking northwest along San Pablo Ridge Trail

I forget my feet for awhile as the wind picks up. This is usually the case on the ridge trails in Wildcat Canyon. I’ve been in winds so strong up here they suck the saliva right out of your mouth and whip it onto your face. Keeping your mouth closed doesn’t save you from this indignity, however, because the winds perform the same action on your nose. Yuck. It’s not quite so windy this time, but I can see rain in the distance, and know I may not be dry at the end of this hike. The sky, land, and water are spectacular from up here, at this time of day, in this weather. I pull on a lightweight wool sweater and this, with my shorts, keeps me perfectly comfortable temperature-wise. The wind is swaying the golden grasses like a wavy sea, and they’re glowing and shimmering in the varied light. The sky is blue, white, silver, and steel gray, and gauzy curtains in the same shade indicate scattered rainfall. After quite a time on long, level Nimitz Way, I take San Pablo Ridge and Belgum Trails, curvy and hilly, exciting in their winding, rising and falling changeability but hard on my weary knees on the downhills. I think the shoes I wore on my last hike like this were better.

In Wildcat Canyon Regional Park, panoramic view with San Pablo Bay, Richmond, and Mt. Tamalpais in the distance (‘Mt. Tam’ to us locals) from the San Pablo Ridge Trail

Among many other things (I’m tired, and my attention is waxing and waning), Plutarch tells of Solon’s meeting with Croesus, and my ears perk up. I remember this story as told by Herodotus. Croesus (as in the saying ‘rich as Croesus’), receives Solon ostensibly as an honored guest, but really as a potential propaganda tool. He wants to impress Solon so that Solon will spread the word about the great riches, power, and glory he’s beheld in Croesus’ court. But Solon, like Plutarch’s other most admired heroes thus far, is unimpressed by such vulgar shows of wealth. The harder Croesus tries, the less Solon is impressed. Instead, he foretells the doom that such wealth is liable to bring Croesus. And sure enough, it attracts the notice of King Cyrus of Persia, who sweeps in with his army and takes all that nice gold and treasure by force. As he is about to execute Croesus, Cyrus’ attention is caught by Cyrus’ lament that he had not heeded Solon’s wisdom. Cyrus decides to spare Croesus’ life when he observes that Croesus has grown wise in turn. It doesn’t do to execute wise men so long as you are strong enough to benefit from their wisdom while keeping them in their place.

For the last mile or so, I hike in a light rain. It feels good. Then about 7 o’clock, I read my destination: Alvarado Staging Area of Wildcat Canyon near the northwest end of the park. I borrow a kind stranger’s cell phone, since mine is malfunctioning, and check on my ride, my always supportive and patient sister Therese. She’ll arrive shortly. I shelter under an oak tree, take off my shoes and socks (oh, sweet relief!) and watch the drops fall from a partly sunny sky. A young girl emerges from her house down the street and places herself in the rainfall in surprise and delight; we watch the water steam off the asphalt that, until a few moments ago, was warmed by the sun. My sister and her boyfriend Eric (who has also become my friend) pick me up and whisk me away to feast with them on papusas and beer. On our way, we see a rainbow glowing against the blue and gray to our left. It’s been a rich and thoroughly satisfying day.

*Listen to the podcast version here or on Google Play, or subscribe on iTunes

~ Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and inspiration:

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy: Inferno, Houghton, Mifflin, 1885

Graham, Daniel W., ‘Heraclitus‘, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta

Plutarch, Lucius Mestrius (c. 46 – c. 120), Parallel Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, translated by Bernadotte Perrin (1847 – 1920), Volumes 1, 2, 3, and 4, recordings at Librivox.org

Zakaria, Fareed. ‘What America Could Learn From Singapore About Racial Integration’. The Washington Post, June 25, 2015

I came across this excellently clear and succinct piece by Chris Cameron on intellectual history, which discipline I’m currently studying at the University of Edinburgh:

I came across this excellently clear and succinct piece by Chris Cameron on intellectual history, which discipline I’m currently studying at the University of Edinburgh:

Aimé-Fernand-David Césaire was a poet, playwright, philosopher, and politician from Martinique. In his long life (1913-2008), Césaire accomplished much in each of these roles, a rare feat as they rarely coincide in one person!

Aimé-Fernand-David Césaire was a poet, playwright, philosopher, and politician from Martinique. In his long life (1913-2008), Césaire accomplished much in each of these roles, a rare feat as they rarely coincide in one person!