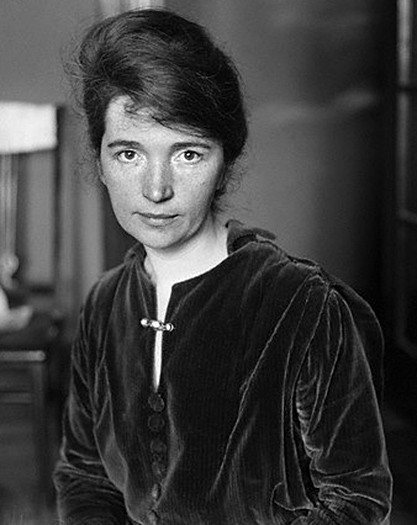

Margaret Sanger, photo probably taken Jan 30th 1917, photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

There’s been a widespread and concerted effort to vilify Margaret Sanger and remove her name from the public roll of great contributors to human rights history. In my research for the Sanger project I’m working on, I find scores of examples of this effort every single time I do an internet search using her name.

Last year, for example, Ted Cruz and some other conservative politicians called for her portrait to be removed from the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC, where her portrait bust is included in the Struggle for Justice exhibition. In justification of his campaign, Cruz used part of a quote lifted from its original context and presented it as saying something nearly opposite of what it was originally meant to say. In a letter to a friend, Sanger expressed her worry that her birth control clinic project in the South might be misperceived and misrepresented as racist; Cruz lifted a few words from this very letter to ‘prove’ that it was. He may have borrowed this idea from Michael Steele, former chairman of the Republican Party, and Ben Carson and Herman Cain, one-time Republican presidential hopefuls. These three influential conservative men, in turn, likely received this bit of distorted wisdom, directly or indirectly, from Angela Davis and some others in the black power movement who, concerned that the reproductive justice movement might have ill effects in the long run on the empowerment of black people, (mis)represented Sanger’s words, works, and character in the worst possible light. The radical origin of the charges of racism against Sanger may surprise followers of these conservative political figures who have passed them along. And what was this purported insight into Margaret Sanger’s character? Why, that she was so racist that she wanted to exterminate the black race through preventing the conception of ensuing generations.

In my research and in early responses to my publications from my Sanger project I’ve also encountered frequent charges that she was a eugenicist, which is true, and in league with or at least sympathetic to Nazi beliefs, which is false.

So, let’s first consider Margaret Sanger’s beliefs and whether they justify her inclusion among the great American freedom leaders. Then, let’s consider her beliefs in the light of her own time and whether they deserve admiration today, on the whole, or are at least understandable given the circumstances of her time.

Gregory Peck and June Havoc in Gentleman’s Agreement

As to Nazism, Sanger is actually an early and particularly vociferous opponent, much more so than many others in an America so rife with anti-Jewish sentiment in her time. I was surprised many years ago, in my late teens or early twenties, when I watched an old Gregory Peck movie (I’ve always been quite a fan of that talented and oh-so-handsome man) in which he played a reporter planning to write an exposé on the issue. To discover how prevalent anti-Semitism really was in America, his character Philip Schuyler Green goes undercover, putting it out there to his friends and colleagues that he was, in fact, Jewish, and had just never happened to mention it before. It doesn’t take long for his work and then his whole life to fall apart as he experiences terrible discrimination, his friends and colleagues turning against him one by one. At that time, I was surprised to learn that when Peck made this movie, anti-Semitism in America was enough of a thing that a major motion picture star would make a movie about it.

Theodore Roosevelt, American President and yes, a eugenicist too

But Sanger is a eugenicist. This belief in the power of genetic inheritance to cure the ills of humankind by selectively breeding them out of existence was widely accepted at the time, even by such luminaries as our own President, Theodore Roosevelt. Eugenics is often divided into two types, positive and negative, and eugenicists are now often judged now by which of these they promoted. Positive eugenics is the idea that healthy, intelligent, hard-working, creative, and wealthy people should have more children so as to increase the stock of human beings who will, in turn, pass down desirable genetic traits. Roosevelt was a eugenicist of this sort. Negative eugenics is the idea that disabled, diseased, unintelligent, idle, and poor people should have fewer children so as to decrease the stock of human beings who will, in turn, pass down negative traits. The latter brand of eugenics can be further broken down into two camps, with differing ideas as to how it could be brought about: that decreased breeding of the ‘unfit’ should be entirely voluntary and encouraged through education, or, that it should be imposed by certain authorities. (Proponents of positive eugenics could also be broken down this way but I have yet to find an example of imposed human breeding of the ‘fit’, though Communist Romanian president Nicolae Ceaușescu’s policies on reproduction could conceivably be considered a sort of coercive positive eugenics).

Sanger promotes negative as well as positive eugenics principles, but as to whether she believes it should be voluntary or coerced, she’s incoherent at best. At times she’s opposed to any sort of official coercion, as in her many statements against the Nazis and in her stated principle that all human beings, women included and especially, should have the individual right and power to determine their own destinies. Yet she also often declares that since many people are incapable of rational judgment, including the ‘insane’ and the so-called ‘feeble-minded’, others need to make that decision for them. Though she criticizes the Nazis harshly for doing that very thing, she never makes it clear who should do the sterilizations, who should decide, and how coercive they should be if their ‘patients’ refuse. I believe she places herself in a moral dilemma in this matter. She so firmly believes in the power of eugenics to cure the terrible set of human ills that she encounters as a nurse that she wants it, no, needs it, to work. She’s well aware that most people would never consent to such a thing, be it for religious reasons or simply that most people, well or mentally ill, rational or not, naturally recoil at the idea that they should be sterilized because others think they should be. So how to cure these ills in the next generation, since Sanger knows there’s no way they could be cured in her own? That’s the dilemma that Sanger never successfully resolves.

Her vehement opposition to the Nazis goes back, first, to the race issue. One of her main criticisms of the Nazis is not that sterilization is a bad thing in principle, or even that the state might legitimately impose sterilization in special circumstances, such as in the case of criminally insane people (an idea we find abhorrent today but that many in Sanger’s time do not). It’s that the Nazis decide to ‘perfect’ the race along racial lines. To Sanger, this idea is both irrational and unscientific. In Woman and the New Race, she writes glowingly of the great wealth of contributions that people of all races and cultures have always brought and still bring to the world, and that much of the promise of future human greatness lies in this diversity. Since it’s clear that all races include people of great intelligence, health, and abilities, she believes that all races should be likewise bettered through eugenics, both positive and negative, and the latter only if and when necessary (though again, she’s incoherent on this point). Sanger is opposed to ‘human waste’, as she puts it, not only of human beings she considers physically and mentally ‘unfit’, but also the human waste of the lives of those children born in such numbers only to have many of them suffer terribly before dying early deaths, often taking their mothers with them; or permanently disabled by hard factory labor, malnutrition, and neglect; or shipped off as cannon fodder. She’s also opposed to the waste of human potential, of throwing away the great contributions, genetic and otherwise, of the best and brightest of all races to the human race as a whole. In this, she reminds me of Alexander Hamilton, who also argues against the waste of human potential inherent in race-based slavery.

It seems to me, in hindsight, that though many of her eugenics beliefs are founded on bad science, or rather, pseudoscience posing as science, they do not come from a malicious place. They form in the mind of a woman who cares enough about her fellow human beings to devote many years of her early adulthood nursing the poor immigrants in the slums of the Lower East Side of New York City, something few of us have the courage or the vision to do. Sanger is appalled by the suffering and privation she witnesses and desperately wants to help these people, especially the women and children who bear the brunt of society’s ills, but she recognizes that she and her fellow nurses don’t have a prayer of keeping up with the ever-growing need. And she realizes that even if they could keep up with the pace, they were only treating suffering that didn’t need to exist in the first place. She believes, over time, that she’s found the answer.

So given all of this, I ask again, why single out Margaret Sanger for such hatred? Why not call for, say, Teddy Roosevelt’s portrait to be taken down, or those of the many others who held problematic beliefs whose portraits hang, without challenge, on the National Portrait Gallery walls?

And why hate Sanger so much as to spread three major falsehoods about her, again and again and again, that have been so often and thoroughly debunked?

The first lie and second lies, as we’ve considered, are that Sanger’s a racist and a Nazi sympathizer. The other lie is that she’s pro-abortion. In fact, if we look at her writings, we find she’s more anti-abortion than anything.

Flyer for Sanger Clinic, Brownsville, Brooklyn, image courtesy of the Margaret Sanger Papers Project

The fact that Sanger is opposed to abortion in most circumstances may surprise many people, especially many conservatives, though I believe the Sanger-as-abortionist lie is as prevalent and persistent as it is because her views on abortion are as politically inconvenient to many on the left, so they don’t trouble to contradict it. She does allow that there are some extreme circumstances in which it is permissible, such as to save the life of the mother (a standard we adhere to today), and she can’t bring herself to blame the women who resort to abortion out of desperation. It’s the Comstocks,the self-righteous anti-sex moralists, the Pope, priests, and bishops, the government, the medical establishment, and the exploitative labor system that cause abortions, not desperate women. They’re the victims. In fact, as you can see from the flyer for her groundbreaking birth control clinic, Sanger lists the prevention of abortion as one of the clinic’s primary purposes.

And yet, the hatred of Sanger rages unabated in so many quarters. There’s plenty to criticize in her eugenics beliefs, in fact, enough to make the three lies I’ve just discussed seemingly unnecessary if you feel the need to discredit her. Again, other people who have had a dramatic impact on our history, like her, are complicated and had some bad ideas, but no Cruzes, Steeles, and Cains are so vehemently, and I would say dishonestly, trying to undermine the validity of every part of their life’s work and demand that their legacy be erased from our public institutional memory. They’re not calling for the removal of the portraits of anti-Semitic Henry Ford or pro-Nazi Charles Lindbergh, for example. To be certain, there are such efforts on the left to challenge the legacies and even mostly discredit influential historical figures such as Cecil Rhodes, Woodrow Wilson, and Thomas Jefferson. But those are for things they actually did: promoting imperial colonialism, instituting scores of racist laws in our nation’s capital, and owning slaves. The debate is only whether their legacies, on the whole, are worthy of respect and admiration.

So I ask again: why single out Margaret Sanger for such a degree of hatred and slander, given her work with the immigrant poor and minorities, her strong anti-Nazism, and her anti-abortionism? Why is she not excused for her flawed eugenics ideas on the understanding that she was a woman of her time, or that the good parts of her legacy outshine and thus have outlasted the bad, as we excuse so many others of our flawed heroes? In New York City, teeming with statues, monuments, and portraits of noteworthy historical figures, I could find no monument to her, however modest, in the city she called home for so long and served so well in such difficult circumstances.

When it comes to Cruz and many others who are adamantly anti-Sanger, I strongly suspect that one of their primary objections to her is really her anti-Catholicism and irreligion. For example, Cruz is a self-proclaimed, unapologetically religious man who, like many prominent conservative politicians these days, often stresses the Christian heritage of the United States. He’s also often regarded as a proponent of dominionism, the idea that the Christian faith should guide all matters of government, because of his frequent praise of his father, who promotes that ideology. To Cruz’s credit, in his 2016 Republican convention speech he stated that religious freedom includes the freedom to be an atheist, in contrast to a declaration he made a year ago that only a religious person is fit to be president of the United States. But the targeting of Sanger by Cruz, and Carson, and Cain, based on easily-disproved, thoroughly-debunked attacks on her character, makes me wonder how committed such conservative leaders are to the idea that Americans should be free to believe in accordance with their conscience and their reason.

Margaret Sanger Portrait Bust, image credit National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian, Washington DC

So why hate Margaret Sanger? Could it simply be because she was a strong woman, a fearless woman, a truly self-liberated woman who did not chase after monetary success or choose acceptable or glamorous routes to fame, an outspoken atheist who stood up to such a powerful man as the Pope… in other words, a self-realized, so-fully-human woman that she’s a mass of greatnesses, ordinarinesses, and deep flaws? For all of our self-assurances that we’ve achieved a sex-equal, religiously tolerant society which places such a high value on free speech, are too many of us still unable to accept such women?

I’m quite sure the answer is yes.

Listen to the podcast version here, on Google Play, or on iTunes

This piece is also published at Darrow, a forum for ideas and culture

Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and inspiration:

‘Birth Control or Race Control? Sanger and the Negro Project‘ The Margaret Sanger Papers Project Newsletter #28 (Fall 2001)

Cruz, Ted. ‘2016 Republican National Convention Speech‘, abcnews.go.com, Jul 21, 2016

Davidson, Amy. ‘Ted Cruz vs. Margaret Sanger’s Portrait‘. New Yorker, Oct 28, 2015

Davis, Angela. Women, Race, & Class. New York: Random House, 1981.

Fea, John. ‘Ted Cruz’s campaign is fueled by a dominionist vision for America‘. The Washington Post: Religion (Commentary), Feb 4th, 2016

‘Gentleman’s Agreement (1947)‘, from IMDB

Jenkinson, C.lay. ‘Self-Soothing by way of Erasing the Complexity of Human History‘. Clayjenkinson.com, Dec 28, 2015

‘Nicolae Ceaușescu‘. Encyclopædia Britannica

Parkinson, Justin. ‘Why is Cecil Rhodes Such a Controversial Figure?‘ BBC News Magazine, Apr 1, 2015

‘The Sanger-Hitler Equation‘, The Margaret Sanger Papers Project Newsletter #32 (Winter 2002/2003)

Sanger, Margaret. The Pivot of Civilization, 1922. Free online version courtesy of Project Gutenberg, 2008, 2013.

Sanger, Margaret. Woman and the New Race, 1920. Free online version courtesy of W. W. Norton & Company

Sullivan, Martin. ‘Margaret Sanger Portrait‘: talk for Face-to-Face, National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian

‘The Portraits: Margaret Sanger‘ from the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian website

Wirestone, Clay. ‘Did Margaret Sanger believe African-Americans “should be eliminated”?‘ PolitiFact, October 5th, 2015