Sick of hearing about Josh Duggar yet?

I sure am. But it’s not the volume of reporting and public gossip on the story that’s making me sick. It’s the way we simultaneously fear and drool over stories that reveal that children have sexual instincts too. It’s the way our laws and the media punish children, often for the rest of their lives, for this very fact. And it’s the way that far too many of my fellow freethinkers, supposedly enlightened and sex-positive, have jumped on the bandwagon in their zeal to ‘get at’ the Duggars.

In case you haven’t heard, Josh is the 27 year old son of celebrity parents Michelle and Jim Bob Duggar, a conservative Christian couple whose practice of rampant childbearing (19 at this point) made them the subject of a popular reality television show.

It turns out that Josh was a kid like many other kids: as a young teen, he touched other children, some far younger than himself, in a sexual manner. Most of it was light petting, or touching of the genital area through clothing. I couldn’t find evidence that there was any violence or physical coercion involved. At some point Josh went to his parents and confessed, and over time, law enforcement was called in, and all those involved received counseling.

It started out with gossip, then somehow, someone got Arkansas authorities to release the police report, which was splashed all over the news by trashy celebrity-gossip publication InTouch Weekly. While names and pronouns were redacted, it became clear that the report was about Josh, and he and his family ‘fessed up. At the request of one of the recipients of the unwelcome touching, the record was destroyed.

Even my fellow freethinkers and sex-positivists have joined in the fray. While giving half-hearted disclaimers to their spreading Josh Duggar ‘molestation’ tales (a strong term for the type of non-violent, secret petting described) even though he was a child at the time, they’re so eager to get at Michelle and Jim Bob that their scruples have fled them.

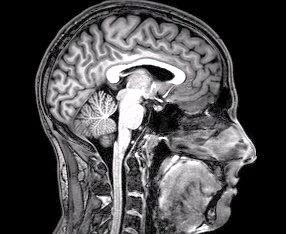

Deeply disappointing. While it’s right that children taught to respect the bodily integrity of others and the importance of consent, it’s also true that children are insatiably curious, with immature brains that lack the structures adults rely on for self-control. C’mon, people. Don’t you have any memory at all of what it’s like to be a little bag of hormones lacking a developed prefrontal cortex? Don’t you remember the storms of emotion and urges, which we could hardly make sense of or control, that raged through us and seemed to take over our minds and bodies? Yes, children have bodies with parts, and sometimes they explore their budding sexuality by touching each other on these parts. We need to get over it and grow up, if we are to be the wise and just helpers children need as they grow up.

Whether or not their intentions were protective or self-serving, the Duggar parents did the right thing by shielding their child from the media circus. They probably did the right thing by privately turning to law enforcement to help teach their recalcitrant young son that actions have consequences and that there are personal boundaries that must be respected. They definitely did the right thing by seeking counseling, even if the counseling could have been of better quality. This is not a story, as many are portraying it, that echoes the clergy child abuse scandals of the last few decades. Those were real sexual crimes perpetuated on children by adults who are far more capable of self-control, and who wield a sort of power that children, as Josh was at the time, do not possess.

Correct children for their mistakes, punish them appropriately to discourage unacceptable behavior, but do not pillory them in the media and do not punish them for the rest of their lives for their childhood wrongdoing. This is true even if the person is now an adult. We do not hold adults to account for what they did as children because we believe in accountability and personal responsibility. To gossip about the mistakes and misdemeanors of children now grown is disgusting and morally reprehensible, because it teaches people that it’s no use to try and become a better person if society will always punish you no matter how you better yourself in the future. Shame on you, Rachel Ford of Friendly Atheist, usually such a good forum for critical thinking. Shame on you, Ana Kasparian and company on the Young Turks, for waiting till near the end of your video commentary to make a halfhearted disclaimer that kids’ disciplinary records shouldn’t be made public, after you passed along this gossip in such an unbalanced and salacious manner. And shame on all of you who joined in this witch hunt.

There’s yet another story that I recently heard about a man who was put on a sex offender registry because he, as a child, had sexual contact with another child. The young man in the story did wrong, but he reformed. Yet he and his family are still suffering the consequences, as are thousands just like him (often for offenses as minor as showing a photo of a body part to another minor, consensually or not), and may be suffering for the rest of his life. There’s nothing so cruel as a simultaneously sex-obsessed and sex-fearing society toward a registered ‘sex offender’, regardless of how they got the label. Think of that young man, of Josh, and of how every single one of our lives could be destroyed if our childhood mistakes were held over our heads in perpetuity.

If people want to criticize the Duggar parents for making a circus of their family and exposing their small children to the stress and danger of life in the limelight (think of the Jackson family and how celebrity affected those kids), well and good. But LEAVE THE KIDS OUT OF IT.

Sources:

Bryan, Miles. For Juvenile Sex Offenders, State Registries Create Lifetime of Problems’. All Things Considered, NPR. May 28th, 2015. http://www.npr.org/2015/05/28/410251735/for-juvenile-sex…

Ember, Sydney. ‘Josh Duggar Molested Four of His Sisters, His Parents Tell Fox News’, New York Times, June 4th 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/04/business/media/josh-duggar-molested…

Ford, Rachel. ‘What the Rush to Defend Josh Duggar Tells Us About Conservative Christian Morality’, Friendly Atheist blog. http://www.patheos.com/blogs/friendlyatheist/2015/05/27/what-…

‘Josh Duggar Chilling Molestation Confession In New Police Report’, InTouch Weekly, June 3 2015

http://www.intouchweekly.com/posts/josh-duggar-chilling-molestation-confession-in-new-police…

‘Josh Duggar’s Child Molestation History Revealed’, The Young Turks, May 22nd 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_MEjjV_jcCc

personal responsibility: if we do wrong, we pay the price. A central feature of our justice system, after all, is the right to a fair

personal responsibility: if we do wrong, we pay the price. A central feature of our justice system, after all, is the right to a fair

The title might make you think it’s not a serious work, that it’s tongue-in-cheek, even a parody of a philosophy book.

The title might make you think it’s not a serious work, that it’s tongue-in-cheek, even a parody of a philosophy book.