Is morality objective, or subjective?

Is morality objective, or subjective?

If it’s objective, it seems that it would need to be something like mathematics or the laws of physics, existing as part of the universe on its own account. But then, how could it exist independently of conscious, social beings, without whom it need not, and arguably could not, exist? Is ‘objective morality’, in that sense, even a coherent concept?

If it’s subjective, how can we make moral judgments about, and demand moral accountability from, people of times, backgrounds, belief systems, and cultures different than our own? If it’s really subjective and we can’t make those kinds of moral judgments or hold people morally accountable, then what’s the point of morality at all? Is ‘subjective morality’ a coherent concept either?

Take the classic example of slavery, which today is considered among the greatest moral evils, but until relatively recently in human history was common practice: could we say it was morally wrong for people in ancient times, or even two hundred years ago, to own slaves, when most of the predominantly held beliefs systems and most cultures supported it, or at least allowed that it was acceptable, if not ideal? Does it make sense for us to judge slave owners and traders of the past as guilty of wrongdoing?

From the objective view, we would say yes, slavery was always wrong, and most people just didn’t know it. We as a species had to discover that it was wrong, just as we had to discover over time, through reason and empirical evidence, how the movements of the sun, other stars, and the planets work.

From the subjective view, we would say no. We can only judge people according to mores of the time. But this is not so useful, either, because one can legitimately point out that the mere passage of time, all on its own, does not make something right become wrong, or vice versa. (This is actually a quite common unspoken assumption in the excuse ‘well, those were the olden days’ when people want to excuse slavery in ancient ‘enlightened, democratic’ Greece, or in certain pro-slavery Bible verses.) In any case, some people, even back then, thought slavery was wrong. How did they come to believe that, then? Was the minority view’s objections to slavery actually immoral, since they were contrary to the mores their own society, and of most groups, and of most ideologies?

Morality can be viewed as subjective in this sense: morality is secondary to, and contingent upon, the existence of conscious, social, intelligent beings. It really is incoherent to speak of morality independently of moral beings, that is, people capable of consciousness, of making and understanding their own decisions, of being part of a social group, because that’s what morality is: that which governs their interactions, and makes them right or wrong. Morality can be also viewed as subjective in the sense that moral beliefs and practices evolved as human beings (and arguably, in some applications of the term ‘morality’, other intelligent, social animals) evolved.

Morality can be viewed as objective in this sense: given that there are conscious, social beings whose welfare is largely dependent on the actions of others, and who have individual interests distinct from those of the group, there is nearly always one best way to act, or at least very few, given all the variables. For example, people thought that slavery was the best way to make sure that a society was happy, harmonious, and wealthy. But they had not yet worked out the theoretical framework, let alone have the empirical evidence, that in fact societies who trade freely, have good welfare systems, and whose citizens enjoy a high degree of individual liberty, are in fact those that end up increasing the welfare of everyone the most, for the society as well as for each individual. So slavery was always wrong, given that we are conscious, social, intelligent beings, because as a practice it harmed human beings in all of these aspects of human nature. Slavery is destructive to both the society and the individual, but many people did not have a reasonable opportunity to discover that fact, other than through qualms aroused by sympathetic observation of so much suffering.

In sum: it appears that in many arguments over morality, where people accuse each other of being ‘dogmatic’, or of ‘moral relativism’, or various other accusations people (I think) carelessly throw at each other, is due to a basic misunderstanding. To have an ‘objective’ view does not necessarily entail one must have a fixed, eternal, essentialist view of morality which does not allow for moral evolution or progress. Likewise, to have a ‘subjective’ view of morality does not entail thinking that ‘anything goes’, or that morality is entirely relative to culture, religion, or belief system. Here, as is the case with so many important issues, simplistic, black-and-white explanations do not lead to understanding, nor to useful solutions to life’s most pressing problems.

* Also published at The Dance of Reason, Sac State’s philosophy blog

Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

![Letter 'I', James Tissot [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/674ea-brooklyn_museum_-_capital_letter_i_-_james_tissot.jpg?w=319&h=320) ee will and the self. What are they? While they are the two most important phenomena to each and every one of us, they’re notoriously hard to describe. Of course, we ‘know’ what they are: respectively, they are the experience, the feeling, of being in control of our own actions, of our thoughts and behaviors, and of having an identity and a personality that exists over time. Without them, our lives seem pointless: if we have no free will, then we are mere automatons, and we can take no credit and no responsibility for anything we do. If we have no self, then there is no we, no ‘I’, at all.

ee will and the self. What are they? While they are the two most important phenomena to each and every one of us, they’re notoriously hard to describe. Of course, we ‘know’ what they are: respectively, they are the experience, the feeling, of being in control of our own actions, of our thoughts and behaviors, and of having an identity and a personality that exists over time. Without them, our lives seem pointless: if we have no free will, then we are mere automatons, and we can take no credit and no responsibility for anything we do. If we have no self, then there is no we, no ‘I’, at all.![Enon robot - By Ms. President (Flickr User) (http://www.flickr.com/photos/granick/211744073/) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/80eb8-enon_robot.jpg?w=240&h=320) discovered that our actions result from the cause-and-effect processes of a physical brain, then we have no free will: our actions and all our thoughts are determined by the cause-and-effect laws of nature. And since we’ve discovered that the sense of self arises from the confluence of the workings of the parts of the brain, and damage or changes to those parts can cause radical changes to our personalities and the ways we feel about the world and ourselves, that the self is an illusion too.

discovered that our actions result from the cause-and-effect processes of a physical brain, then we have no free will: our actions and all our thoughts are determined by the cause-and-effect laws of nature. And since we’ve discovered that the sense of self arises from the confluence of the workings of the parts of the brain, and damage or changes to those parts can cause radical changes to our personalities and the ways we feel about the world and ourselves, that the self is an illusion too.![The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp - Unknown after Rembrandt - Photo by Jillf64 ({University of Edinburgh}) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/95bbb-eu464_unknown_after_rembrandt_-_the_anatomy_lesson_of_dr_tulp.jpg?w=400&h=307) time, human beings invented and developed the scientific method pioneered by Francis Bacon, and began to more carefully examine the correlations of disease symptoms with the circumstances in which they occurred (outbreaks of cholera mapped so that the epidemic was revealed to center on a polluted source of drinking water in 1830’s London; the correlation of damage to a particular parts of the brain to the symptoms of brain damaged patients; the dissection of corpses, comparing diseased organs to healthy ones). With the discoveries of the physical causes of disease, by pathogens and by damage to parts of the body, effective cures were finally able to be developed.

time, human beings invented and developed the scientific method pioneered by Francis Bacon, and began to more carefully examine the correlations of disease symptoms with the circumstances in which they occurred (outbreaks of cholera mapped so that the epidemic was revealed to center on a polluted source of drinking water in 1830’s London; the correlation of damage to a particular parts of the brain to the symptoms of brain damaged patients; the dissection of corpses, comparing diseased organs to healthy ones). With the discoveries of the physical causes of disease, by pathogens and by damage to parts of the body, effective cures were finally able to be developed.

I’ve been tentatively planning to go to Chirnside, the place where Hume grew up. The house is no longer there, but the gardens are, and the place where the house was is well marked. The fares turn out to be quite expensive, and since the house isn’t there anymore, it seems a lot to pay since I’m traveling on the cheap. I decide to spend the money instead enjoying my remaining time in Edinburgh, immersed in the place, eating locally made delicious food. So I go and have some marvelous pastries at The Manna House instead, planning to visit Chirnside next time I’m here, hopefully on a bike tour.

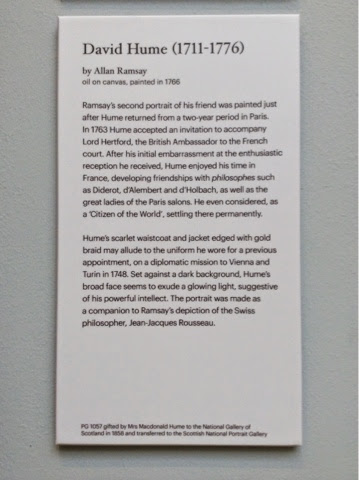

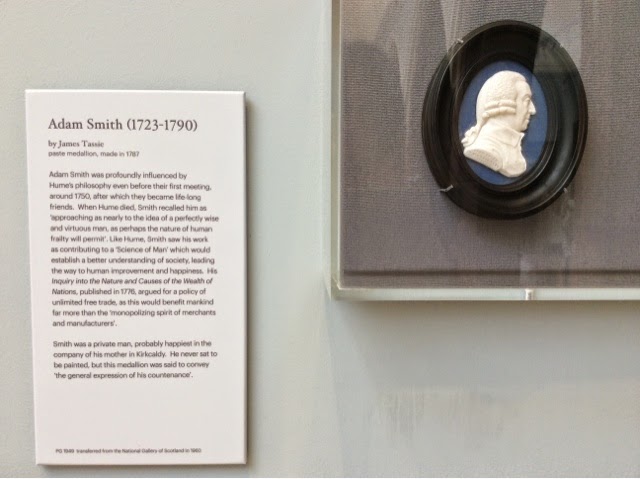

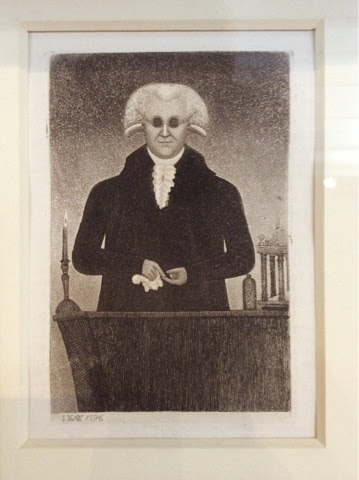

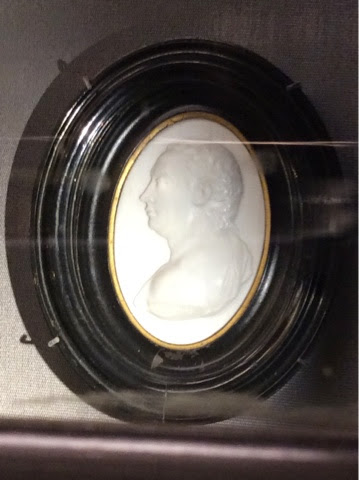

I’ve been tentatively planning to go to Chirnside, the place where Hume grew up. The house is no longer there, but the gardens are, and the place where the house was is well marked. The fares turn out to be quite expensive, and since the house isn’t there anymore, it seems a lot to pay since I’m traveling on the cheap. I decide to spend the money instead enjoying my remaining time in Edinburgh, immersed in the place, eating locally made delicious food. So I go and have some marvelous pastries at The Manna House instead, planning to visit Chirnside next time I’m here, hopefully on a bike tour. The last of the David Hume-related sites I visit today is the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. It’s even more beautiful than I expected, inside and out. Sculptures of Hume and his friend Adam Smith, philosopher and economist who wrote The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, adorn the southeast tower.

The last of the David Hume-related sites I visit today is the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. It’s even more beautiful than I expected, inside and out. Sculptures of Hume and his friend Adam Smith, philosopher and economist who wrote The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, adorn the southeast tower.

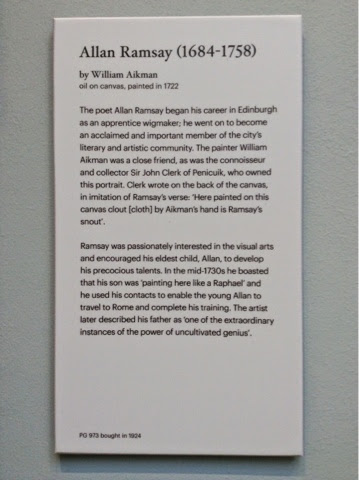

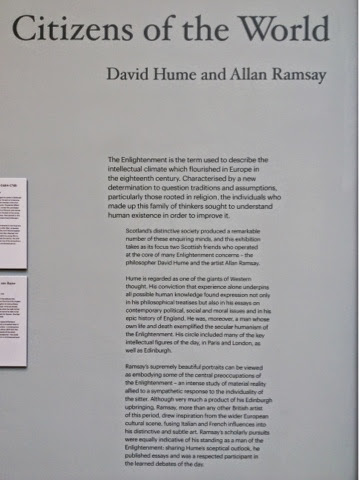

Here’s a little more about Allan Ramsey, David Hume, and the Scottish Enlightenment….

Here’s a little more about Allan Ramsey, David Hume, and the Scottish Enlightenment…. .

.

![Woman writing, Gerard ter Borch [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/f7781-woman2bwriting252c2bgerard2bter2bborch2b255bpublic2bdomain255d252c2bvia2bwikimedia2bcommons.jpg?w=292&h=400)