M y friends: –In undertaking the inquiry of the existence of a God, I am fully conscious of the difficulties I have to encounter. I am well aware that the very question produces in most minds a feeling of awe, as if stepping on forbidden ground, too holy and sacred for mortals to approach. The very question strikes them with horror, as is owing to this prejudice so deeply implanted by education, and also strengthened by public sentiment, that so few are willing to give it a fair and impartial investigation, –knowing but too well that it casts a stigma and reproach upon any person bold enough to undertake the task, unless his previously known opinions are a guarantee that his conclusions would be in accordance and harmony with the popular demand. But believing as I do, that Truth only is beneficial, and Error, from whatever source, and under whatever name, is pernicious to man, I consider no place too holy, no subject too sacred, for man’s earnest investigation; for by so doing only can we arrive at Truth, learn to discriminate it from Error, and be able to accept the one and reject the other.

y friends: –In undertaking the inquiry of the existence of a God, I am fully conscious of the difficulties I have to encounter. I am well aware that the very question produces in most minds a feeling of awe, as if stepping on forbidden ground, too holy and sacred for mortals to approach. The very question strikes them with horror, as is owing to this prejudice so deeply implanted by education, and also strengthened by public sentiment, that so few are willing to give it a fair and impartial investigation, –knowing but too well that it casts a stigma and reproach upon any person bold enough to undertake the task, unless his previously known opinions are a guarantee that his conclusions would be in accordance and harmony with the popular demand. But believing as I do, that Truth only is beneficial, and Error, from whatever source, and under whatever name, is pernicious to man, I consider no place too holy, no subject too sacred, for man’s earnest investigation; for by so doing only can we arrive at Truth, learn to discriminate it from Error, and be able to accept the one and reject the other.

No is this the only impediment in the way of this inquiry. The question arises, Where shall we begin? We have been told, that “by searching none can find out God” which has so far proved true; for, as yet, no one has ever been able to find him. The most strenuous believer has to acknowledge that it is only a belief, but he knows nothing on the subject. Where, then, shall we search for his existence? Enter the material world; ask the Sciences whether they can disclose the mystery? Geology speaks of the structure of the Earth, the formation of the different strata, of coal, of granite, of the whole mineral kingdom. –It reveals the remains and traces of animals long extinct, but gives us no clue whereby we may prove the existence of a God.

Natural history gives us a knowledge of the animal kingdom in general; the different organisms, structures, and powers of the various species. Physiology teaches the nature of man, the laws that govern his being, the functions of the vital organs, and the conditions upon which alone health and life depend…. But in the whole animal economy–though the brain is considered to be a “microcosm”, which which may be traced a resemblance or relationship with everything in Nature–not a spot can be found to indicate the existence of a God.

Mathematics lays the foundation of all the exact sciences. It teaches the art of combining numbers, of calculating and measuring distances, how to solve problems, to weigh mountains, to fathom the depths of the ocean; but gives no directions how to ascertain the existence of a God.

Astronomy tells us of the wonders of the Solar System–the eternally revolving planets, the rapidity and certainty of their motions, the distance from planet to planet, from star to star. It predicts with astonishing and marvelous precision the phenomena of eclipses, the visibility upon our Earth of comets, and proves the immutable law of gravitation, but is entirely silent on the existence of a God.

In fine, descend to the bowels of the Earth, and you will learn what it contains; into the depths of the ocean, and you will find the inhabitants of the great deep; but neither in the Earth above, nor the waters below, can you obtain any knowledge of his existence. Ascend into the heavens, and enter the “milky way,” go from planet to planet and to the remotest star, and ask the eternally revolving systems, Where is God? and Echo answers, Where?

The Universe of Matter gives us no record of his existence. Where next shall we search? Enter the Universe of Mind, read the volumes written on the subject, and in all the speculations, the assertions, the assumptions, the theories, and the creeds, you can only find Man stamped in an indelible impress his own mind on every page. In describing his God, he delineated his own character: the picture he drew represents in living and ineffaceable colors the epoch of his existence–the period he lived in.

It was a great mistake to say that God made man in his image. Man, in all ages, made his God in his own image, and we find that just in accordance with his civilization, his knowledge, his experience, his taste, his refinement, his sense of right, of justice, of freedom, and humanity, –so has he made his God. But whether coarse or refined; cruel and vindictive, or kind and generous; an implacable tyrant, or a gentle and loving father; it still was the emanation of his own mind –the picture of himself.

But, you ask, how came it to be that man thought or wrote about God at all? The answer is very simple. Ignorance is the mother of Superstition. In proportion to man’s ignorance he is superstitious–does he believe in the mysterious. The very name has a charm for him. Being unacquainted with the nature and laws of things around him, with the true causes of the effects he witnessed, he ascribed them to false ones–to supernatural agencies. The savage, ignorant of the mechanism of a watch, attributes the ticking to a spirit. The so-called civilized man, equally ignorant of the mechanism of the Universe, and the laws which govern it, ascribes it to the same erroneous cause. Before electricity was discovered, a thunderstorm was said to come from the wrath of an offended Deity. To this fiction of man’s uncultivated mind, has been attributed all of good and evil, or wisdom and of folly. Man has talked about him, written about him, disputed about him, fought about him,–sacrificed himself, and extirpated his fellow man. Rivers of blood and oceans of tears have been shed to please him, yet no one has ever been able to demonstrate his existence.

But the Bible, we are told, reveals this great mystery. Where Nature is dumb, and Man ignorant, Revelation speaks in the authoritative voice of prophecy. Then let us see whether that Revelation can stand the test of reason and of truth.–God, we are told, is omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, –all wise, all just, and all good; that he is perfect. So far, so well; for less than perfection were unworthy of a God. The first act recorded of him is, that he created the world out of nothing; but unfortunately the revelation of Science–Chemistry–which is based not on written words, but demonstrable facts, says that Nothing has no existence, and therefore out of Nothing, Nothing could be made. Revelation tells us that the world was created in six days. Here Geology steps in and says, that it requires thousands of ages to form the various strata of the earth. The Bible tells us the earth was flat and stationary, and the sun moved around the earth. Copernicus and Galileo flatly deny this flat assertion, and demonstrates by Astronomy that the earth is spherical, and revolves around the sun. Revelation tells us that on the fourth day God created the sun, moon, and stars. This, Astronomy calls a moon story, and says that the first three days, before the great torchlight was manufactured and suspended in the great lantern above, must have been rather dark.

The division of the waters above from the waters below, and the creation of the minor objects, I pass by, and come at once to the sixth day.

Having finished, in five days, this stupendous production, with its mighty mountains, its vast seas, its fields and woods; supplied the waters with fishes–from the whale that swallowed Jonah to the little Dutch herring; peopled the woods with inhabitants–from the tiger, the lion, the bear, the elephant with his trunk, the dromedary with his hump, the deer with his antlers, the nightingale with her melodies, down to the serpent which tempted mother Eve; covered the fields with vegetation, decorated the gardens with flowers, hung the trees with fruits; and surveying this glorious world as it lay spread out like a map before him, the question naturally suggested itself. What is it all for, unless there were beings capable of admiring, of appreciating, and of enjoying the delights this beautiful world could afford? And suiting the action to the impulse, he said, “let us make man.” “So God created man in his own image; in the image of God created he him, male and female created he them.”

I presume by the term “image” we are not to understand a near resemblance of face or form, but in the image or likeness of his knowledge, his power, his wisdom, and perfection. Having thus made man, he placed him (them) in the garden of Eden–the loveliest and most enchanting spot at the very head of creation, and bade them (with the single restriction not to eat of the tree of knowledge), to live, to love, and to be happy.

What a delightful picture, if we could only rest here! But did these beings, fresh from the hand of omnipotent wisdom, in whose image they were made, answer the great object of their creation, answer the great object of their creation? Alas! no. No sooner were they installed in their Paradisean home, than they violated the first, the only injunction given them, and fell from their high estate; and not only they, but by a singular justice of that very merciful Creator, their innocent posterity to all coming generations, fell with them! Does that bespeak wisdom and perfection in the Creator, or in the creature? But what was the cause of this tremendous fall, which frustrated the whole design of the creation? The Serpent tempted mother Eve, and she, like a good wife, tempted her husband. But God did not know when he created the Serpent, that it would tempt the woman, and that she was made of such frail materials, (the rib of Adam,) as not to be able to resist the temptation? If he did not know, then his knowledge was at fault; if he did, but could not prevent that calamity, then his power was at fault; if he knew and could, but would not, then his goodness was at fault. Choose which you please, and it remains alike fatal to the rest.

Revelation tells us that God made man perfect, and found him imperfect; then he pronounced all things good, and found them most desperately bad. “And God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and it grieved him at his heart.” “And the Lord said, I will destroy man whom I have created, from the face of the earth; both man and beasts, and the creeping things, and the fowls of the air, for it repenteth me that I have made them.”So he destroyed everything, except Noah with his family, and a few household pets. Why he saved them is hard to say, unless it was to reserve materials as stock in hand to commence a new world with; but really, judging of the character of those he saved, by their descendants, it strikes me it would have been much better, and given him far less trouble, to have let them slip also, and with his improved experience made a new world out of fresh and superior materials. (*see footnote)

As it was, this wholesale destruction even, was a failure. The world was not one jot better after the flood than before. His chosen children were just as bad as ever, and he had to send his prophets, again and again, to threaten, to frighten, to coax, cajole, and to flatter them into good behaviour. But all to no effect. They grew worse and worse; and having made a covenant with Noah after he sacrificed of “every clean beast and of every clean fowl,”–“The Lord smelt the sweet savour; and the Lord said in his heart, I will not again curse the ground any more for man’s sake; for the imagination of man’s heart is evil from his youth; neither will I again smite any more every living thing, as I have done.” And so he was forced to resort to the last sad alternative of sending “his only begotten son,” his second self, to save them. But alas! “his own received him not,” and so he was obliged to adopt the Gentiles, and die to save the world. Did he succeed, even then? Is the world saved? Saved! From what? From ignorance? It is all around us. From poverty, vice, crime, sin, misery, and shame? It abounds everywhere.Look into your poor-houses, your prisons, your lunatic asylums; contemplate the whip, the instruments of torture, and of death; ask the murderer, or his victim; listen to the ravings of the maniac, the shrieks of distress, the groans of despair; mark the cruel deeds of the tyrant, the crimes of slavery, and the suffering of the oppressed; count the millions of lives lost by fire, by water, and by the sword; measure the blood spilled, the tears shed, the sighs of agony drawn from the expiring victims on the altar of fanaticism; –and tell me from what the world was saved? And why was it not saved? Why does God still permit these horrors to afflict the race? Does omniscience not know it? Could omnipotence not do it? Would infinite wisdom, power, and goodness allow his children thus to live, to suffer, and to die? No! Humanity revolts against such a supposition.

Ah! Not now, says the believer. Hereafter will he save them. Save them hereafter! From what? From the apple eaten by our mother Eve? What a mockery! If a rich parent were to let his children live in ignorance, poverty, and wretchedness, all their lives, and hold out to them the promise of a fortune at some time hereafter, he would justly be considered a criminal, or a madman. The parent is responsible to his offspring–the Creator to his creature.

The testimony of Revelation has failed. Its account of the creation of the material world is disproved by science. Its account of the creation of man in the image of perfection, is disproved by its own internal evidence. To test the Bible God by justice and benevolence, he could not be good; to test him by reason and knowledge, he could not be wise; to test him by the light of the truth, the rule of consistency, we must come to the inevitable conclusion that, like the Universe of matter and of mind, this pretended Revelation has also failed to demonstrate the existence of a God.

Methinks I hear the the believer say, you are unreasonable; you demand as impossibility; we are finite, and therefore cannot understand, much less define and demonstrate the infinite. Just so! But if I am unreasonable in asking you to demonstrate the existence of the being you wish me to believe in, are you not infinitely more unreasonable to expect me to believe–blame, persecute, and punish me for not believing–in what you have to acknowledge you cannot understand?

But, says the Christian, the world exists, and therefore there must have been a God to create it. That does not follow. The mere fact of its existence does not prove a Creator. Then how came the universe into existence? We do not know but the ignorance mind of man is certainly no proof of the existence of a God. Yet upon that very ignorance has it been predicated, and is maintained. From the little knowledge we have, we are justified in the assertion that the Universe never was created, from the simple fact that not one atom of it can be annihilated. To suppose a Universe created, is to suppose a time when it did not exist, and that is a self-evident absurdity. Besides, where was the Creator before it was created? Nay, where is he now? Outside of that Universe, which means the all in all, above, below, and around? That is another absurdity. is he contained within? Then he can only be a part, for the whole indeed includes all the parts. If only a part, then he cannot be the Creator, for a part cannot create the whole. But the world could not have made itself. True; nor could God have made himself; and if you must have a God to make the world, you will be under the same necessity to have another to make him, and others still to make them, and so on until reason and common sense are at a stand-still.

The same argument applies to a First Cause. We can no more admit of a first than a last cause. What is a first cause? The one immediately preceding the last effect, which was an effect to a cause in its turn–an effect to causes, themselves effects. All we know is an eternal chain of cause and effect, without beginning as without end.

But is there is no evidence of intelligence, of design, and consequently of a designer? I see no evidence of either. What is intelligence? It is not a thing, a substance, an existence in itself, but simply a property of matter, manifesting itself through organizations. We have no knowledge of, nor can we conceive of, intelligence apart from organized matter; and we find that from the smallest and simplest insect, through all the links and gradations in Nature’s great chain, up to Man–just in accordance with the organism, the amount, and the quality of brain, so are the capacities to receive impressions, the power to retain them, and the abilities to manifest and impart them to others; namely, to have its peculiar nature cultivated and developed, so as to bear mental fruits, just as the cultivated earth bears vegetation–physical fruits. Not being able to recognize an independent intelligence, I can perceive no design or designer except in the works of man.

But, says Paley, does the watch not prove a watchmaker–a design, and therefore a designer? How much more does the Universe?Yes; the watch shows design, and the watchmaker did not leave us in the dark on the subject, but clearly and distinctly stamped his design on the face of the watch. Is it as clearly stamped on the Universe? Where is the design, in the oak to grow to its majestic height? In the formation of the wing of the bird, to enable it to fly, in accordance with the promptings of its nature? or in the sportsman to shoot it down while flying? In the butterfly to dance in the sunshine? or its being crushed in the tiny fingers of a child? Design in man’s capacity for the acquisition of knowledge, or in his groping in ignorance? In the necessity to obey the laws of health, or in the violation of them, which produces disease? In the desire to be happy, or in the causes that prevent it, and make him live in toil, misery, and suffering?

The watchmaker not only stamped his design on the face of the watch, but he teaches how to wind it up when it runs down; how to repair the machinery when it is out of order; and how to put a new spring in when the old one is broken, and leave the watch as good as ever. Does the great Watchmaker, as he is called, show the same intelligence and power in keeping, or teaching others to keep, this complicated mechanism–Man–always in good order? and when the life-spring is broken replace it with another, and leave him just the same? If an Infinite Intelligence designed man to possess knowledge, he could not be ignorant; to be healthy, he could not be diseased; to be virtuous, he could not be vicious; to be wise, he could not act so foolish as to trouble himself about the Gods, and neglect his own best interests.

But, says the believer, here is a wonderful adaptation of means to ends; the eye to see, the ear to hear, &c. Yes, this is very wonderful; but not one more jot so, than if the eye were made to hear, and the ear to see. The supporters of Design use sometimes very strange arguments. A friend of mine, a very intelligent man, with quite a scientific taste, endeavored once to convince me of a Providential design, from the fact that a fish, which has always lived in the Mammoth Cave of Kentucky, was entirely blind. Here, said he, is strong evidence; in that dark cave, where nothing was to be seen, the fish need no eyes, and therefore has none. He forget the demonstrable fact that the element of light is indispensable in the formation of the organ of sight, without which it could not be formed, and no Providence, or Gods, could enable the fish to see. That fish story reminds me of the Methodist preacher who proved the wisdom and benevolence of Providence in always placing the rivers near large cities, and death at the end of life; for Oh! my dear hearers, said he, what could have become of us had he placed it at the beginning?

Everything is wonderful, and wonderful just in proportion as we are ignorant; that that proves no “design” or “designer”. But did things come by chance? It exists only in the perverted mind of the believer, who, while insisting that God was the cause of everything, leaves Him without any cause. The Atheist believes as little in the one as in the other. He knows that no effect could exist without an adequate cause, and that everything in the Universe is governed by laws.

The Universe is one vast chemical laboratory, in constant operation, by her internal forces. The laws or principles of attraction, cohesion, and repulsion, produce in never-ending succession the phenomena of composition, decomposition, and recomposition. The how, we are too ignorant to understand, to modest to presume, and too honest to profess. Had man been a patient and impartial inquirer, and not with childish presumption attributed everything he could not understand, to supernatural causes, given names to hide his ignorance, but observed the operations of Nature, he would undoubtedly have know more, been wiser, and happier.

As it is, Superstition has ever been the greatest impediment to the acquisition of knowledge. Every progressive step of man clashed against the two-edged sword of Religion, to whose narrow restrictions he had but too often to succumb, or march onward at the expense of interest, reputation, and even life itself.

But, we are told, that Religion is natural; the belief in a God universal. Were it natural, then it would indeed be universal, but it is not. We have ample evidence to the contrary. According to Dr. Livingstone, there are whole tribes or nations, civilized, moral, and virtuous; yes, so honest that they expose their goods for sale without guard or value set upon them, trusting to the honesty of the purchaser to pay its proper price.

Yet these people have not the remotest idea of a God, and he found it impossible to impart it to them. And in all the ages of the world, some of the most civilized, the wisest, and the best, were entire unbelievers; only they dared not openly avow it, except at the risk of their lives. Proscription, the torture and the stake, were found most efficient means to seal the lips of heretics; and though the march of progress has broken the infernal machines, and extinguished the fires of the Inquisition, the proscription, and the more refined but not less cruel and bitter persecutions of an intolerant and bigoted public opinion, in Protestant countries, as well as in Catholic, on account of belief, are quite enough to prevent men from honestly avowing their true sentiments upon the subject. Hence there are few possessed of the moral courage of a Humboldt.

If the belief in a god were natural, there would be no need to teach it. Children would possess it as well as adults, the layman as the priest, the heathen as much as the missionary. We don;t have to teach the general elements of human nature;–the five senses, seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and feeling. They are universal; so would religion be were it natural, but it is not. On the contrary, it is an interesting and demonstrable fact, that all children are Atheists, and were religion not inculcated into their minds they would remain so. Even as it is, they are great sceptics, until made sensible of the potent weapon by which religion has ever been propagated, namely, fear–fear of the lash of public opinion here, and a jealous, vindictive God hereafter. No; there is no religion in human nature, nor human nature in religion. It is purely artificial, the result of education, while Atheism is natural, and, were the human mind not perverted and bewildered by the mysteries and follies of superstition, would be universal.

But the people have been made to believe that were it not for religion, the world would be destroyed–man would become a monster, chaos and confusion would reign supreme. These erroneous notions conceived in ignorance, propagated by superstition, and kept alive by an interested and corrupt priesthood who fatten on the credulity of the public, are very difficult to be eradicated.

But sweep all the belief on the supernatural from the face of the earth, and the world would remain just the same. The seasons would follow each other in their regular succession; the stars would shine in the firmament; the sun would shed his benign and vivifying influence of light and heat upon us; the clouds would discharge their burden in gentle and refreshing showers; and cultivated fields would bring forth vegetation; summer would ripen the golden grain, ready for harvest; the trees would bear fruits; the birds would sing in accordance with their happy instinct, and all Nature would smile as joyously around us as ever. Nor would man degenerate. Oh! no. His nature, too would remain the same. He would have to be obedient to the physical, mental, and moral laws of his being, or to suffer the natural penalty for their violation; observe the mandates of society, or receive the punishment. His affections would be just as warm, the love of self-preservation as strong, the desire for happiness and fear of pain as great. He would love freedom, justice, and truth, and hate oppression, fraud, and falsehood, as much as ever.

Sweep all belief in the supernatural from the globe, and you would chase away the whole fraternity of spectres, ghosts, and hobgoblins, which have so befogged and bewildered the human mind, that hardly a clear ray of the light of Reason can penetrate it. You would cleanse and purify the heart of the noxious, poisonous weed of superstition, with its bitter, deadly fruits–hypocrisy, bigotry, and intolerance, and fill it with charity and forbearance towards erring humanity. You would give man courage to sustain him in trials and misfortune, sweeten his temper, give him a new zest for the duties, the virtues, and the pleasures of life.

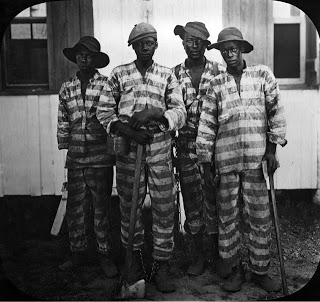

Morality does not depend on the belief in any religion. History gives ample evidence that the more belief the less virtue and goodness. Nor need we go back to ancient times to see the crimes and atrocities perpetrated under its sanction. Look at the present crisis–at the South with 4,000,000 of human beings in slavery, bought and sold like brute chattels under the sanction of religion and of God, which the Reverends Van Dykes and Raphalls of the North fully endorse, and the South complains that the reforms in the North are owing to Infidelity. Morality depends on accurate knowledge of the nature of man, of the laws that govern his being, the principles of right, of justice, and of humanity, and the conditions requisite to make him healthy, rational, virtuous, and happy.

The belief in a God has failed to produce this desirable end. On the contrary, while it could not make man better, it has made him worse; for in preferring blind faith in things unseen and unknown to virtue and morality, in directing his attention from the known to the unknown, from the real tot he imaginary, from the certain here to a fancied hereafter, from the fear of himself, of the natural result of vice and crime, to some whimsical despot, it perverted his judgment, degraded him in his own estimation, corrupted his feelings, destroyed his sense of right, of justice, and of truth, and made him a moral coward and a hypocrite. The lash of a hereafter is no guide for us here. Distant fear cannot control present passion. It is much easier to confess your sins in the dark, than to acknowledge them in the light; to make it up with a God you don’t see, than with a man whom you do. Besides, religion has always left a back door open for sinners to creep out of at the eleventh hour. But teach man to do right, to love justice, to revere truth, to be virtuous, not because a God would reward or punish him hereafter, but because it is right; and as every act brings its own reward or its own punishment, it would best promote his interest by promoting the welfare of society. Let him feel the great truth that our highest happiness consists in making all around us happy, and it would be an infinitely truer and safer guide for man to a life of usefulness, virtue, and morality, than all the beliefs in all the Gods ever imagined.

The more refined and transcendental religionists have often said to me, if you do away with religion, you would destroy the most beautiful element of human nature–the feeling of devotion and reverence, ideality, and sublimity. This, too, is an error. These sentiments would be cultivated just the same, only we would transfer the devotion from the unknown to the known; from the Gods who, if they existed, would not need it, to man who does. Instead of reverencing an imaginary existence, man would learn to revere justice and truth. Ideality and sublimity would refine his feelings, and enable him to admire and enjoy the ever-changing beauties of Nature; the various and almost unlimited powers and capacities of the human mind; the exquisite and indescribable charms of a well-cultivated, highly refined, virtuous, noble man.

But not only have the priests tried to make the very term Atheism odious, as if it would destroy all of good and beautiful in Nature, but some of the reformers, not having the moral courage to avow their own sentiments, wishing to be popular, fearing lest their reforms would be considered Infidel, (as all reforms assuredly are,) shield themselves from the stigma, by joining in the tirade against Atheism, and associate it with everything that is vile, with the crime of slavery, the corruptions of the Church, and all the vices imaginable. This is false, and they know it. Atheism protests against this injustice. No one had a right to give the term a false, a forced interpretation, to suit his own purposes (this applies also to some of the Infidels who stretch and force the term Atheist out of its legitimate significance). As well we might use the terms Episcopalian, Unitarian, Universalist, to signify vice and corruption, as the term Atheist, which means simply a disbelief in a God, because finding no demonstration of his existence, man’s reason will not allow him to believe, nor his conviction to play the hypocrite, and profess what he does not believe. Give it its true significance, and he will abide the consequences; but don’t fasten upon it the vices belonging to yourselves. Hypocrisy is the mother of a large family!

In conclusion, the Atheist says to the honest conscientious believer, Though I cannot believe in your God which you have failed to demonstrate, I believe in man; if I have no faith in your religion, I have faith, unbounded, unshaken faith in the principles of right, of justice, and humanity. Whatever good you are willing to do for the sake of your God, I am full as willing to do for the sake of man. But the monstrous crimes the believer perpetrated in persecuting and exterminating his fellowman on account of differences of belief, the Atheist, knowing that belief is not voluntary, but depends on evidence, and therefore there can be no merit in the belief of any religions, nor demerit in a disbelief in all of them, could never be guilty of. Whatever good you would do without fear of punishment, the Atheist would do simply because it is good; and being so, he would receive the far surer and more certain reward, springing from well-doing, which would constitute his pleasure, and promote his happiness.

![1865 Ernestine L. Rose petition signature [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/45224-rose_signature_1865_petition.jpg?w=400&h=45)

‘A Defense of Atheism’ by Ernestine Rose. Reproduced with permission from Women Without Superstition: No Gods – No Masters, The Collected Writings of Women Freethinkers of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Edited by Annie Laurie Gaylor. Madison, Wisconsin 1997.

https://ffrf.org/shop/women-without-superstition-no-gods-no-masters

***************************************************************************

* Note: In the paragraph regarding the story of Noah’s flood, Ernestine Rose could be interpreted as having a negative view of human nature, or she could be satirizing religious views of human nature as intrinsically evil and in need of redemption from some power outside of itself. From her other writings, it appears to be the latter; in her writings overall, she reveals her more positive view of human nature. For example, consider this quote: “I have endeavored to the best of my powers and ability to serve the cause and progress of humanity, to advocate what seemed to be the truth; to defend human nature from the libel cast upon it by superstition…” (Dorress-Worters, Paula. Mistress of Herself: Speeches and Letters of Ernestine Rose, Early Women’s Rights Leader. The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2008, p. 208)

![Picadilly police separate football fans, By Vintagekits (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0), GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/39b9e-piccadilly_police_split_zenit_and_rangers.jpg?w=389&h=292)

y friends: –In undertaking the inquiry of the existence of a God, I am fully conscious of the difficulties I have to encounter. I am well aware that the very question produces in most minds a feeling of awe, as if stepping on forbidden ground, too holy and sacred for mortals to approach. The very question strikes them with horror, as is owing to this prejudice so deeply implanted by education, and also strengthened by public sentiment, that so few are willing to give it a fair and impartial investigation, –knowing but too well that it casts a stigma and reproach upon any person bold enough to undertake the task, unless his previously known opinions are a guarantee that his conclusions would be in accordance and harmony with the popular demand. But believing as I do, that Truth only is beneficial, and Error, from whatever source, and under whatever name, is pernicious to man, I consider no place too holy, no subject too sacred, for man’s earnest investigation; for by so doing only can we arrive at Truth, learn to discriminate it from Error, and be able to accept the one and reject the other.

y friends: –In undertaking the inquiry of the existence of a God, I am fully conscious of the difficulties I have to encounter. I am well aware that the very question produces in most minds a feeling of awe, as if stepping on forbidden ground, too holy and sacred for mortals to approach. The very question strikes them with horror, as is owing to this prejudice so deeply implanted by education, and also strengthened by public sentiment, that so few are willing to give it a fair and impartial investigation, –knowing but too well that it casts a stigma and reproach upon any person bold enough to undertake the task, unless his previously known opinions are a guarantee that his conclusions would be in accordance and harmony with the popular demand. But believing as I do, that Truth only is beneficial, and Error, from whatever source, and under whatever name, is pernicious to man, I consider no place too holy, no subject too sacred, for man’s earnest investigation; for by so doing only can we arrive at Truth, learn to discriminate it from Error, and be able to accept the one and reject the other.

![[Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons - Source=Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds. History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1, 1848-1861 (New York: Fowler & Wells, 1881), opp. p. 97. |Date=1881](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5e5b1-ernestinerose2b1.jpg?w=232&h=346)

![By sconosciuto [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/8efa5-elizabeth_stanton.jpg?w=238&h=348)

![1917 Photograph of a woman working in a munitions factory, Chilwell, Nottinghamshire, England. By Nicholls Horace [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/92eca-working2bwoman.png?w=234&h=320)