A view of the interior of David Hume’s grave monument, Edinburgh, Scotland

There is one argument that seldom fails to come up in discussions with religious people who feel the deep need to persuade you to share their beliefs: that religion is the only thing that can bring real consolation, to overcome the fear of death. When I was a child, and through my twenties, I was often seized with that fear; with my grandmother’s death, the first deep grief I’d ever known, it really hit hard for awhile.

Yet it was in those same years that I was religious, or had recently come out of it, that I experienced most of that fear.

I began to wonder: can that association between religion and fear of death be something like smoking? The smoking creates the need to smoke, and then is the only relief for the urge to smoke again. I think there might be something in that idea, at least in the sense that since most religions bring up the subject of death a lot, it’s harder to shake the fear if you’re constantly reminded. But really, people have been afraid of death for at least as long as they’ve been creating art, literature, and religions that express it. The origins of that fear must be a feature of human psychology, or at least a common by-product of it.

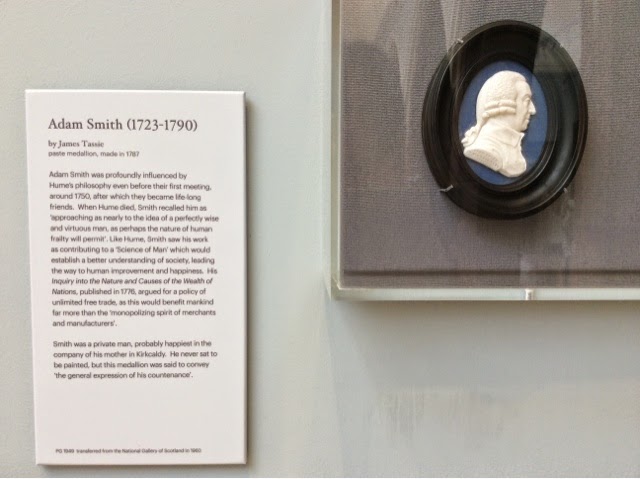

The death of Socrates has long been held up as the prime example of a good death, a death faced with composure and courage (if you’ve never read it, I encourage you to discover that moving, fascinating story!) Seneca, Epicurus, and many other great philosophers have shown us, through words and example, how death can be devoid of fear. I turn to a somewhat more modern example: the account I’m reading that Adam Smith wrote, of the death of his close friend David Hume, my favorite philosopher.

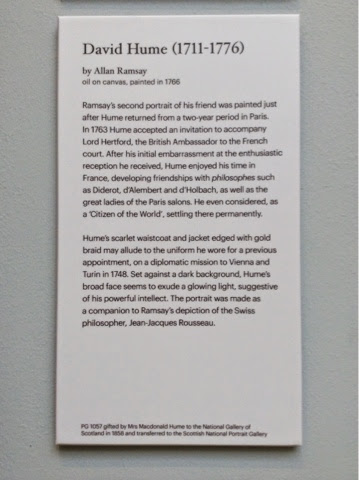

Hume was widely considered to be a skeptic and an atheist, and therefore a dangerous person, a corrupting influence. His naturalistic, practical, sensible philosophy revealed the impossibility of miracles and of knowing whether or not imperceptible things exist, and implied the lack of necessity for the existence of god(s). For his own safety and financial stability, Hume’s friends, as well as his own prudence, convinced him not to publish all he actually wrote, including one of his most important works, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, until after his death.

Adam Smith’s account of Hume’s death is one such that any us us could wish for. When Hume discovered he (probably) had intestinal cancer, he resigned himself to enjoying the time he had left, and making the best as well as the most, of it. After all, he said, ‘…a man of sixty-five, by dying, cuts off only a few years of infirmities…’ Hume continued to entertain and to visit friends, play cards, travel, write and edit, and do as much as his waning strength would let him. When he could finally no longer get out of bed, sit up for long, or leave his home, he passed the time in his favorite way, by reading, and dictating letters to his loved ones.

Here’s what Smith had to say, regarding how both the habits of a lifetime, and terminal illness, highlighted the true character of his friend Hume:

‘His temper, indeed, seemed to be more happily balanced… than that perhaps of any other man I have ever known. Even …the lowest state of his fortune… never hindered him from exercising… acts both of charity and generosity…. The extreme gentleness of his nature never weakened either the firmness of his mind, or the steadiness of his resolutions. His constant pleasantly was the genuine effusion of good-nature and good humor, tempered with delicacy and modesty… And that gaiety of temper …which is so often accompanied with frivolous and superficial qualities, was in him certainly attended with… the most extensive learning, the greatest depth of thought, and a capacity in every respect the most comprehensive. Upon the whole, I have always considered him, both in his lifetime and since his death, as approaching as nearly to the idea of a perfectly wise and virtuous man, as perhaps the nature of human frailty will permit.’ What a tribute!

David Hume’s grave monument, Calton Hill, Edinburgh, Scotland

The physician who attended his death wrote:

‘He continued to the last perfectly sensible, and free from much pain or feelings of distress. He never dropped the smallest expression of impatience; but when he had occasion to speak to the people about him, always did it with affection and tenderness…. [H]e died in such such a happy composure of mind, that nothing could exceed it.’

So how does a David Hume, a Socrates, a Seneca, or you, or I, live a life full of joy and virtue and free of the fear of death?

I’m not talking about living a perfect life, here. For one thing, I think the idea of ‘perfection’ is weird to apply to human beings, indeed any biological entity. The concept is too abstract, only applicable to such things as mathematics, logic, and geometry, when describing things such as numbers, and either/or distinctions, and the degree of the angles in a Euclidean triangle. Biological things, most especially human beings, are complicated, full of conflicting emotions, needs, desires, interests, and so on.

But there are ways to get though life that help you achieve happiness and goals worth having, and there are ways that don’t. And there are people (and some other animals, of course!) who exemplify ways of living that are so successful, and so admirable, that it’s an excellent idea to observe them, especially given that we are social creatures who depend on one another for edification and support.

So when it comes to living that life full of joy and virtue, relatively free of that fear of death, I think we would all do well not to look to an ideology, like a religion or some utopian ideal, or some such panacea. I’d look, rather, to a person who lived well, and consider how their character, how their general outlook on life, how their habits contributed to it. This would apply to anyone, secular or religious, anyone.

But especially to lovers of philosophy. Philosophy, that love of wisdom, has been a love of mine for a long time, much longer than I knew what it was, how to identify it. From the time I was little, i was fascinated by the (mostly theological, sometimes political, sometimes otherwise strictly philosophical) discussions that often went on around the dinner table when the adults got together. And I would badger my dad with endless questions on such matters, my poor patient Dad!

By the time I returned to college the second time, I knew what I wanted to spend my time really getting into these fascinating topics, of how and why the world works, and how we should best go about living in it. And here I am, doing the same thing, but now sharing the discussion with all of you who take an interest, because it’s my firm conviction that philosophy is something pretty much all of us engage in, so often that it’s one of the most ordinary things we do.

But making philosophy a more central part of my life has been one of the most happy-making things in it. There’s a wonderfully titled book by a sixth-century thinker, Boethius, called The Consolation of Philosophy, written when he was going through the worst time of his life, imprisoned, facing execution. It’s such an excellent book title that it’s become an ordinary phrase, usually pluralized (I’ve used it for years before I ever found out where it came from). Like Boethius, like Socrates, like Seneca and Hume, I know that even if I had the great misfortune of facing the loss of the most treasured things in my life: my loving and beloved husband, my family and friends, my health and my possessions, I would have a way to keep my best self intact.

Philosophy is among the greatest ways, if not the greatest, to make sense not only out of day to day realities, it puts you closely in touch with the largest and most important things, and helps you realize your connections to them so deeply, that in a very real way you never fully lose your loves, your family, your friends, and it turns out that while some possessions are wonderful and worth having, they’re never worth so much that the loss of them should destroy you.

Living a life with philosophy now a conscious interest and pursuit has enabled me to live a richer and fuller life, and helps me day to day to figure out ways to make it better, and to overcome those difficulties I still have. I have high hopes that will enable me become at least a bit as admirable as these great people I’ve mentioned here, and many many more whom I have not. And not only does this hope rule my life: fear, including that of death, no longer does.

– Written in the Rare Books Reading Room of the Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, on my David Hume travel writing trip, May 2014

Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and inspiration:

De Botton, Alain. ‘Seneca on Anger’ from the BBC series Philosophy: A Guide to Happiness, 2000.

Hume, David. Life of David Hume. (Includes his short autobiography My Own Life, and a letter from Adam Smith to William Strahan. Printed in London, 1777.

Konstun, David. ‘Epicurus’, 2014. The Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epicurus/#4

I’m sitting here in James Court, having a pint at the Jolly Judge, under a cozy little overhang, watching the rain fall all around me. It started out as a sunny day, with a brilliant blue sky with scattered big puffy white clouds, probably even a hot spring day by Scottish standards.

I’m sitting here in James Court, having a pint at the Jolly Judge, under a cozy little overhang, watching the rain fall all around me. It started out as a sunny day, with a brilliant blue sky with scattered big puffy white clouds, probably even a hot spring day by Scottish standards.

over to Calton Hill, to say farewell to the mortal remains of the great thinker I came here to discover in his hometown. As anyone would in my place, I feel deeply moved, my chest tight, my eyes prickly. Is there someone you deeply admire, where you’ve often felt that bittersweet ache that you so wish you could meet them, knowing you never could except through the artifacts, and more importantly, the words and ideas, they left behind? Then you know how I’m feeling just now.

over to Calton Hill, to say farewell to the mortal remains of the great thinker I came here to discover in his hometown. As anyone would in my place, I feel deeply moved, my chest tight, my eyes prickly. Is there someone you deeply admire, where you’ve often felt that bittersweet ache that you so wish you could meet them, knowing you never could except through the artifacts, and more importantly, the words and ideas, they left behind? Then you know how I’m feeling just now.

About ten minutes after I go inside, I hear the rain start to pour, and see the lightning flash through the skylight. I decide this would be a good place to linger ’till they close at five. And as soon as I leave, the rain abruptly stops, and I’m greeted to this spectacular sky again:

About ten minutes after I go inside, I hear the rain start to pour, and see the lightning flash through the skylight. I decide this would be a good place to linger ’till they close at five. And as soon as I leave, the rain abruptly stops, and I’m greeted to this spectacular sky again:

I’ve been tentatively planning to go to Chirnside, the place where Hume grew up. The house is no longer there, but the gardens are, and the place where the house was is well marked. The fares turn out to be quite expensive, and since the house isn’t there anymore, it seems a lot to pay since I’m traveling on the cheap. I decide to spend the money instead enjoying my remaining time in Edinburgh, immersed in the place, eating locally made delicious food. So I go and have some marvelous pastries at The Manna House instead, planning to visit Chirnside next time I’m here, hopefully on a bike tour.

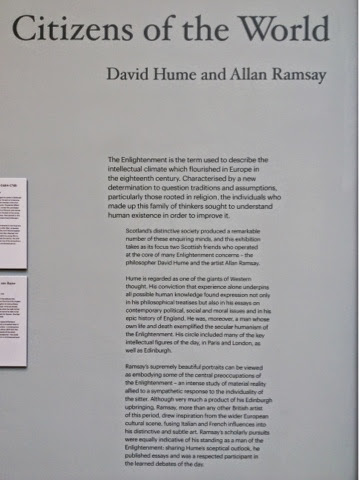

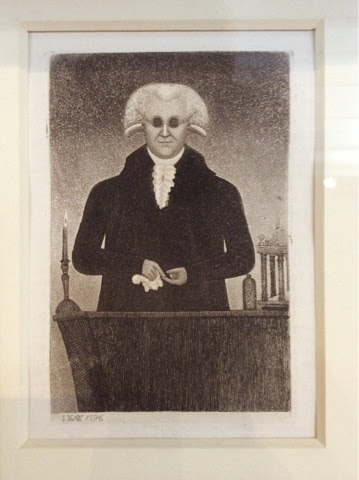

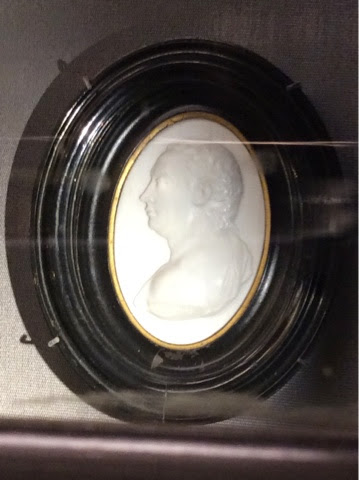

I’ve been tentatively planning to go to Chirnside, the place where Hume grew up. The house is no longer there, but the gardens are, and the place where the house was is well marked. The fares turn out to be quite expensive, and since the house isn’t there anymore, it seems a lot to pay since I’m traveling on the cheap. I decide to spend the money instead enjoying my remaining time in Edinburgh, immersed in the place, eating locally made delicious food. So I go and have some marvelous pastries at The Manna House instead, planning to visit Chirnside next time I’m here, hopefully on a bike tour. The last of the David Hume-related sites I visit today is the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. It’s even more beautiful than I expected, inside and out. Sculptures of Hume and his friend Adam Smith, philosopher and economist who wrote The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, adorn the southeast tower.

The last of the David Hume-related sites I visit today is the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. It’s even more beautiful than I expected, inside and out. Sculptures of Hume and his friend Adam Smith, philosopher and economist who wrote The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, adorn the southeast tower.

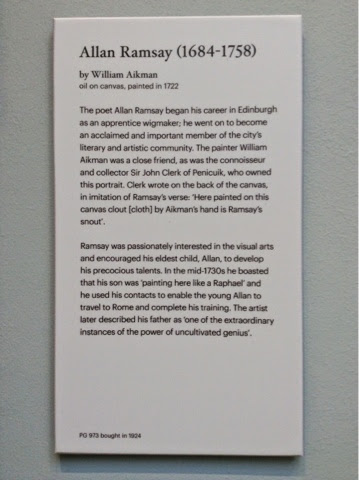

Here’s a little more about Allan Ramsey, David Hume, and the Scottish Enlightenment….

Here’s a little more about Allan Ramsey, David Hume, and the Scottish Enlightenment…. .

.

Thursday, May 08, 2014

Thursday, May 08, 2014

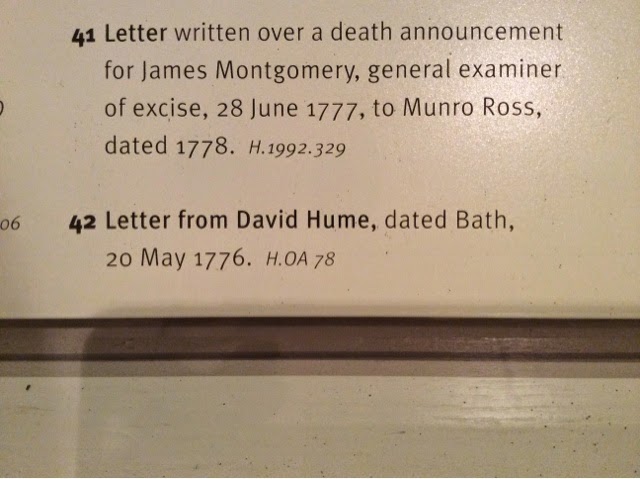

There’s this great little addendum to an edition of Hume’s Political Discourses, a first edition printed in Edinburgh by R. Fleming in 1752, called Scotticisms, that I came across in my research.

There’s this great little addendum to an edition of Hume’s Political Discourses, a first edition printed in Edinburgh by R. Fleming in 1752, called Scotticisms, that I came across in my research.

I head back downhill a little from the park at the top of the hill, and Calton Hill Cemetery is on my left. I go through the gate and up the short flight of steps, and a bit ahead to my right, I find Hume’s elegant and rather simple monument and gravesite. I spend a good bit of time here musing: the power of physical objects to really bring things into focus still never fails to surprise me, and my sense of purpose in this journey to Edinburgh is strengthened.

I head back downhill a little from the park at the top of the hill, and Calton Hill Cemetery is on my left. I go through the gate and up the short flight of steps, and a bit ahead to my right, I find Hume’s elegant and rather simple monument and gravesite. I spend a good bit of time here musing: the power of physical objects to really bring things into focus still never fails to surprise me, and my sense of purpose in this journey to Edinburgh is strengthened.