I’m at Monticello with my dad, John Cools! I’m one happy gal

Sixth day, April 24th, 2015.

Today, I’m heading south of D.C., and have only two destinations for the day, and that’s a good thing: it’ll take every hour I have to explore them, and make me wish I have more to spend. These places tell the story of what Thomas Jefferson’s all about more than any of the other sites I visited, with the possible exception of the Library of Congress (though he never visited the building, of course, since it was built decades after his death).

And this time, I’m pleased to say, I have a travel companion, that very special person I told you I was meeting yesterday: my darling Dad, John Cools! He’s one of my very favorite people in the whole world, and I can’t imagine a better person to go on a history tour with. He’s also handsome, like his big brother Bob, who lives in nearby Falls Church and took me on the little driving tour on the first D.C. day of this trip.

Groves Store, Somerville Post Office, farmland in Fauquier County, Virginia, photo by Emridout via Wikimedia Commons

Groves Store and Somerville Post Office, surrounded by farmland in Fauquier County, Virginia, is itself the self-described “Downtown Somerville”. Photo by Emridout via Wikimedia Commons

We drive to Charlottesville via the smaller highways that take us through the beautiful Virginia farmlands, lush and green and still colorful with wildflowers. We lose a few extra minutes getting out of town, since we’re so busy chatting and laughing that we miss a couple of turns. After these brief false starts, we’re on our way.

Since I’m driving and absorbed in conversation with my Dad, I forget to ask him to be my photographer, and have no photos from the drive to share. However, I find a great one online that’s in the public domain; thank you, Emridout! Remove the hay bales, and you’re seeing more or less what we see during our drive.

Thomas Jefferson’s final site plan for Monticello on display at the visitor center museum

We arrive at Monticello, Jefferson’s stately home on the hill in Albemarle County, Virginia, just a few miles away from where he was born at Shadwell. (Monticello is Italian for ‘little mountain’.) His childhood home burned down when he was in his mid-twenties, and though I was tempted to find the site, I think it’s best to first see the main places we came to to see, and stop by Shadwell if we have time later. Turns out, we don’t.

First, we head to the ticket machine for the house tour.We’re scheduled for a tour a few hours later, so we start with the museum. It’s an excellent one.

Tools like these would have been used in building Monticello, on display at the visitor center museum

We start with the exhibit which shows how Monticello was designed and built in stages. In fact, it was never really finished. Jefferson was an experimental architect, and I guess he’d be considered an amateur, in the sense that although he designed buildings, he wasn’t paid to do it for a living and he wasn’t formally trained. It was one of his lifelong interests, however, and at Monticello, he’d often build up part of the house, only to see a building or illustration which gave him a better idea. So, he’d tear part of it down from time to time, redesign, and rebuild it.

Thomas Jefferson’s standing desk, in the Monticello museum. Doesn’t look like it would have been quite tall enough for his six-foot-two-inch self!

My Dad is a construction superintendent and started out in his professional life framing houses and building room additions; he’s also built or assisted in building many houses from the ground up. He used to take us kids with him to work sometimes, usually one or two at a time, and we would play with the wood scraps and little round metal cutouts from electrical boxes (which make perfect coins for buried treasure). Dad often says how much he misses building with his own hands, but a superintendent commands a much better salary and he had a family to support, so a superintendent he became. If Jefferson were here, they’d have a lot to talk about.

This exhibit is right up my Dad’s alley, and he pores over the displays in great interest. I’m interested too, but I’m more drawn to Jefferson’s standing desk displayed in the center of the room, as antique furniture is a little more my forte. It’s both elegant and practical; I would love to own it. With its tilt top and pull-out additional work surface, it’s just as great for the laptop and reference books I’m working with as it was for Jefferson’s pen and paper. My day job is in a medical office, and I often regret the number of hours I spend sitting down. This would be a perfect solution.

Bust of Thomas Jefferson by Jean-Antoine Houdon, 1789

We head for the gallery across the hall whose displays focus on the daily lives of all who lived and worked at Monticello. There’s a handsome bust of Jefferson at the front of gallery, and I find I like the face. It’s very expressive, a little handsome, with hair that looks awkward to my modern eyes, swept outward from either side of his face.

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Mather Brown (original), at Washington DC’s National Portrait Gallery

I recall a portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Mather Brown, the first known portrait of him painted in London in 1786, which doesn’t look that much to me like the man portrayed in this bust or most of the other portrayals I’ve seen. A copy of this portrait hangs here at Monticello somewhere; the original is on display at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC.

I’ve heard the Brown portrait described as more handsome than Jefferson in real life: he was tall, lanky, with red hair and freckles and a long nose. But I like the face portrayed in the bust much better: it looks a bit patrician but with rough edges, the face of an energetic man who spends a lot of time outdoors or doing something else interesting. The Brown portrait looks stuffy and a little haughty in comparison, and I never did like the powdered look.

Thomas Jefferson’s pocket tools and gadgets

A project-oriented, outdoorsy man like Jefferson needed a toolkit, and we see a nifty one in this gallery. There’s a pocketknife, drafting instruments with a little silver case, architect’s scale, and most interesting to me, a sort of tiny notebook made of ivory. It fans out like a lady’s fan, and what’s nifty about it is that you can write notes on it in pencil, and then erase the marks by rubbing them off with your finger, making it available to use again. I use the Pages app on my mini iPad in sorta the same way during my travels.

The gallery has many, many more great exhibits, way too many to picture here!

A view of the graveyard at Monticello, as seen from the path from the museum up to the house

Completing our tour of the museum, we grab a bite to eat at the cafe (they actually have very tasty, reasonably priced food, sometimes even serving vegetables raised in the restored Monticello gardens) and then head up the hill toward the house. It’s a nice little stroll, I think preferable to the shuttle, since it gives you time in nature to refresh yourself between the mental effort of taking in all that history; interesting as it is, it’s fatiguing after awhile, and the break is welcome. The path winds through a pretty little patch of woods, and it’s spring, so the leaves are still small and bright green, and you can see quite a ways through the trees and get a pretty good view of the lay of the land.

A closeup of Thomas Jefferson’s obelisk-tombstone, listing the three self-selected accomplishments he was most proud of

The Jefferson family graveyard is about halfway up the hill to the house from the welcome center, and Jefferson, his wife Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson, his mother Jane Randolph Jefferson, his sister Martha Jefferson Carr, and her husband, his brother-in-law and best friend Dabney Carr. Carr and Jefferson studied law together and both were members of the Virginia House of Burgesses. They were very close since childhood, and would hang out on the hill that would later become the site of Monticello, often reading and talking under the shade of a favorite oak tree. They promised that whoever died first, the other would bury him under that oak. Carr, sadly, died at the early age of thirty, so it was up to Jefferson to fulfill that vow.

Dabney Carr’s grave; he was the first to be buried at Monticello

This graveyard grew up around that first burial, and over the years, his mother-in-law, nieces, nephews, cousins and other family, his wife Martha 38 years later, and finally Jefferson himself, were buried.

The obelisk that is Jefferson’s tombstone towers high above the rest, and besides his name and birth and death dates, it’s carved with a list of his three proudest accomplishments: author of the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and founder of the University of Virginia. Not the presidency of the United States, or his diplomatic service to France, or any of his other achievements in politics, scholarship, law practice, legislation, agriculture, science, architecture, invention, or philosophy, none of these made it onto that stone.

Whatever his flaws, the fact that he directed only these three to be carved on his tombstone increases my respect for him quite a bit. Rights-based government; freedom of conscience; public access to a liberal education: it’s hard to come up with a list of three more valuable social goods. Jefferson did more than most to promote these in his lifetime; even where he didn’t carry out his goals or conceive of better ones, he helped lay the groundwork so that others could implement his ideals of a more enlightened, rational, humane society more fully.

Mulberry Row path and gardens at Monticello

Dad and I pause, gaze, and reflect a little while here, then we continue up the hill. We arrive next at the gardens and Mulberry Row, where many of Jefferson’s slaves and hired contractors lived and worked, including his slave, departed wife’s half-sister, and mistress of 38 years Sally Hemings. The gardens and the Row run side by side to the south of the house.

The gardens are fully restored, laid out in the same way as in Jefferson’s time in accordance with his notes and drawings, and as much as possible, grow what Jefferson’s farm grew, and are as carefully tended.

Chimney and foundation of the joiner’s (woodworker’s) shop on Mulberry Row

Mulberry Row is a fascinating place: there’s been extensive archaeological work done, with many of the foundations of the original structures laid bare and described by signs, interspersed by a few reconstructions. Most of the buildings on the Row burned down or were pulled down when they fell into disrepair, but there are a few structures still standing that are original.

On the west end of the Row stands the chimney and bits of the walls of the joiner’s shop, where the fine woodworking was done: wood molding, furniture, carriages, doors, windows, and so on, from wood that had been imported or felled on the plantation and cut into lumber elsewhere, then brought here. If he needed skilled work done, the practical Jefferson would hire an expert, often from Europe, then apprentice one of his slaves to him so that they could provide the same services in the future. For example, Sally Heming’s half-brother John Hemings became Monticello’s master woodworker after acquiring the skill under the tutelage of David Watson, a hired Scotsman.

Uriah Phillips Levy’s mother’s gravesite on Mulberry Row

One creative and lovely use of one of the crumbling structures on the Row is Uriah Phillips Levy’s mother’s gravesite wall. Levy believed that great people’s homes should be preserved in their memory, and as the first Jewish naval officer in the U.S. who also advocated for religious liberty and against flogging, was a great admirer of Jefferson’s. So, he bought Monticello in the 1830’s to restore and preserve it. When his mother died here, Levy buried her here in this site overlooking the gardens and vista of the woods and green farmlands below.

Textile workshop on Mulberry Row

There are two buildings on Mulberry Row that are original and still more or less intact: the workmen’s house which at some point became a small textile factory, and one of the stables.

Remaining section of the stables on Mulberry Row

The workmen’s house / textile workshop was first built in the 1770’s, and the stables in 1808. The latter was originally a larger, L-shaped building; this is what’s left.

We’re so absorbed in exploring Mulberry Row that we almost don’t notice those that the few hours we had to wait to tour the house had quickly passed. We scurry on over to join our tour group.

Monticello is preserved and run by a private non-profit, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, and many of the artifacts contained in the house are on loan by private collectors. The tour guide explains that since the Foundation has not received permission from the owners of all the artifacts, no photography is allowed inside. So I contact the Foundation and receive permission to use a limited number of the Foundation’s images of the interior.

This may sound like heresy to many, but while Monticello is a very interesting and even impressive house, I don’t consider it particularly beautiful or graceful. It looks just like what it is: a concoction of an experimental architect who loves all things classical and equally loves invention and values practicality, constructed in a piecemeal fashion so that these two aspects of Jefferson’s taste are never reconciled. There are beautiful details and fine craftsmanship throughout the house, even some lovely rooms. But many of the elements don’t fully harmonize with one another and overall, it just doesn’t hang together. That’s fine by me: because it’s such a quirky place, very much a product of an individualist, I find it all the more interesting to explore, and I think it’s a really… well, nifty place.

Monticello Entrance Hall © Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello 2, photo by Robert Lautman, used by permission

We enter the front of the house through a large portico with a pointed lintel, topped with a large weather vane. While the weather vane looks rather funny with the neoclassical design, it pierces the roof and attaches to a dial on the portico ceiling so that the detail-oriented Jefferson could step out onto the front porch and see which way the wind was blowing just by glancing up.

There’s also a giant clock over the inside front door of the entrance hall, which tells not only the time of day but the day of the week, again, somewhat awkwardly. Since the weights suspended from overly long chains hang down through holes cut in the floor, he’d have to go down to the basement to check the day of the week on Saturdays and Sundays if his calendars hadn’t already alerted him. Again, over-the-top tech nerdy gear, still in the process of development, for the 18th century gadget-head.

Monticello Entrace Hall South Wall 2, © Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello, used by permission

As we enter the entrance hall, Jefferson’s fascination with the natural world and the history of local cultures is manifest in the beautifully presented and preserved fossils and Indian artifacts that fill the room. Painted animal skins hang from the interior balcony, shields, spears, pipes, clothing, and the heads and skulls of animals hang on the walls, fossil remains of animals cover tables. Jefferson was an innovator and pioneer in many fields, including archaeology; he’s credited with directing the first scientific archaeological dig in the Americas.

Among the busts and portraits that ring the room, his own is placed across the room from Alexander Hamilton’s, Jefferson’s ideological foe and political nemesis. While he long thought Hamilton’s political beliefs would spell disaster for the new republic if carried out, he ended up using some of Hamilton’s methods to accomplish his own goals as President, such as taking on more national debt to pay for the Louisiana Purchase. Hamilton was a Federalist, and believed that a strong central government, a standing army, industry, and a national debt were necessary for any nation’s success and the liberty and well-being of its inhabitants; Jefferson believed that a small national government, largely independent agrarian states, no standing army, and freedom national debt would accomplish these ends much better. Let that be a lesson to us, as I’m sure it was to Jefferson; it’s always important to remember that others many have insight we haven’t yet had occasion to see clearly for ourselves, and to be ready and able to change our minds when the circumstances reveal that we’re wrong.

Monticello Book Room © Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello, used by permission

We pass thorough a pretty, small blue parlor to the next room that really represents something that Jefferson’s all about: the book room. You may be surprised that Jefferson had such a large library as this in his later years considering he’d sold all his books to Congress in 1815. But as he wrote to John Adams, he couldn’t live without books, so he promptly resumed accumulating more debt by building a new library.

The book collection here is composed of only a few from Jefferson’s actual collection; the rest are identical titles that others had owned. The room does hold one of Jefferson’s actual high-backed easy chairs and an original portrait of Jefferson in profile by Gilbert Stuart, which Jefferson’s friends and family said looked more like him than just about any other portrait.

Monticello Jefferson Cabinet © Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello, used by permission

Then through a beautiful, plant-filled, well-lit greenhouse and hobby room to Jefferson’s ‘cabinet’, or personal office, connected to his bedroom by two passageways. He was a busy man, disciplined in his reading, writing, and keeping of accounts, and wished to be able to get right back to what he was working on as efficiently as possible. So he devised two ways to get from one to the other: one, the standard little hallway which is the one we walk through and two, his alcove bed was set into the dividing wall, so he could roll out of bed to the left into his bedroom, or to the right straight into his office. It’s also the bed he died in, so there would have been plenty of space for his loved ones to bid him goodbye from whatever direction they came. I feel, for a moment, a little like an intruder, since Jefferson was a very private man in many ways, especially concerning matters of the bed, so to speak. But as he said, the world belongs to the living, not the dead, and we the living are here to learn from what he left behind.

Jefferson’s office is an especially interesting and revealing room. It’s full of scientific instruments, an orrery (model of the solar system), a polygraph (a mechanical device which makes a copy of the letter you’re writing while you’re writing it), and gadget-y furniture, including a revolving bookstand which allowed Jefferson to quickly consult several volumes at once, an adjustable-top desk which could be raised, lowered, and angled to suit the needs of the moment, and revolving chair and table. My good friend Alex, who simply must to have or at least try out every new invention that comes along, would drool over this room.

Like the entrance hall, it’s also ringed by portrait busts and images of his friends and influences, including George Washington, James Monroe, and, like Hamilton, a Federalist, but unlike Hamilton, a friend, John Adams. Adams and Jefferson met at the Second Continental Congress in 1775 and became close friends. While they shared a commitment to the Revolution and to the cause of political and personal liberty in general, they differed sharply in some particulars in how this could best be accomplished. Adams held a more pessimistic view of human nature, and thought that a free people needed a stronger government, stricter laws with greater social accountability, and a more aristocratic, pomp-and-circumstance-orientated leadership to inspire and impress. Jefferson held a more optimistic view of human nature, and thought that the people could be trusted to govern themselves if mostly left alone, with government interference only when people infringed on one another’s natural rights. Both emphasized the importance role of education, believing that an uninformed and uneducated populace would always remain vulnerable to exploitation and oppression. Adams thought it should be fully financed at public expense, and Jefferson was a founder of the American system of public higher education (more on that shortly).

We pass through many other interesting and handsome rooms, including the parlor, lined floor to ceiling with portraits, again of Jefferson’s friends and influences. If I were to describe all the rooms in detail, this account would go on far too long, so I refer you to Monticello’s website’s excellent virtual online tour, or better yet, go see it in person! I assure you, you will not be disappointed.

We pass through many other interesting and handsome rooms, including the parlor, lined floor to ceiling with portraits, again of Jefferson’s friends and influences. If I were to describe all the rooms in detail, this account would go on far too long, so I refer you to Monticello’s website’s excellent virtual online tour, or better yet, go see it in person! I assure you, you will not be disappointed.

Leaving the house, we chat just a little with some other tourists. Since we all want photos of ourselves and our companions in front of the house, we oblige one another in turn, and I pose with my handsome Dad and favorite travel buddy. We pause for a little break outside, and take in the view looking down from the hill at the scenery all around. Peering through a little break in the trees, we can see, far off in the distance, our next destination after Monticello.

But we still have some exploring to do here. Monticello is also composed of an L-shaped wing on either side of the house, with the long ends extending past the rear portico. These wings are set below the house, built into the base of the hillock the main house is on with the entry doors facing out, and connect with the basement on either side; the roofs of each these wings form a terrace. At the tail end of each L, there’s a two-story brick building, or pavilion.

View north from Monticello’s west lawn. If you look hard, you can just make out the University of Virginia through the trees

The south pavilion was the first finished house structure at Monticello, composed of two rooms, a combination bedroom and sitting room over a kitchen. Because Shadwell had burned two years earlier, Jefferson moved into this building in 1772, before schedule, with his new wife Martha and his infant daughter, also named Martha but called Patsy. They lived in this little house for nearly two years, until the main house was built up enough to be habitable in 1794.

We head on down below the terrace. The basement and both lower wings of Monticello house more slaves’ quarters, the smokehouse, the dairy, the kitchen, the wine cellar and brewery, the ware room, stables, the wash house, a privy, and numerous other rooms, all full of interesting exhibits showing how a large plantation community raised and produced food, ran a great house, manufactured goods for sale and for consumption, and so on. Again, I very, very highly recommend a visit!

After thoroughly exploring this fascinating place, we realize that a couple more hours had flown by and we needed to skedaddle if we were to reach our next destination in time to tour it in daylight.

Students attending festivities winding down on the Lawn at the University of Virginia

Long porch of students’ quarters at the University of Virginia. The Academical Village was designed to place students and teachers in close proximity and therefore, frequent discourse

We wind our way down the hill toward the University of Virginia, which Jefferson founded in 1819. As aforementioned, you can see the domed roof of the Rotunda between the trees from Monticello looking northwest. I’d bet he kept the trees trimmed from time to time in that direction so that he could look upon what he considered one of the most important accomplishments of his life.

As were so many of Jefferson’s brainchildren, the University was an innovative institution. It was nonsectarian; it was among the first to adopt the elective system; it focused on educating students qualified entirely on the basis of merit, not wealth or social standing; it emphasized the study of the sciences as well as the humanities; and it was built as an ‘academical village’, which emphasized a close association between instructors and students but with private lodgings for the latter, facilitating peaceful study and healthful rest. When we arrive, it’s not exactly peaceful: it appears we’ve caught the tail end of a daytime festival, with tents and booths scattered around, groups of students standing or lolling on picnic blankets, and a live band playing.

A worn pinnacle from Merton College Chapel tower, erected 1451, in one of the University of Virginia’s gardens

The center of the University is arranged around a grand rectangular Lawn, where the festivities are winding down, with the Rotunda Building at the head. It’s a very handsome building, modeled after the Pantheon and exactly half its height and width, where Jefferson much more successfully married the local red brick look with classical design than at Monticello. Jefferson not only designed the Rotunda (with help), he designed the Academical Village, many of the other buildings, the overall layout, even, as I discover on a plaque on one of them, the whimsical wavy garden walls.

The University is a lovely place to stroll, built on hilly green grounds with lots of trees, enchanting little gardens tucked behind student buildings, many containing interesting sculptures or old architectural relics. One has at its center an original ancient, heavily weathered stone spire from Merton College at Oxford dating from 1451. It’s about to turn Friday evening, and the students are out in droves to start off their weekend dressed to impress, laughing, chatting, and jostling their buddies.

My Dad and I wander and chat, discussing what I had learned before the trip of the history of the University and its architecture. It also works out well that our visit coincides with the Rotunda building’s restoration, since, as aforementioned, my Dad has spent his life working in construction. Even though we can’t see the interior, we can observe the process of restoration as well as see many of the Rotunda’s underlying structures exposed, which he finds very interesting.

My Dad and I wander and chat, discussing what I had learned before the trip of the history of the University and its architecture. It also works out well that our visit coincides with the Rotunda building’s restoration, since, as aforementioned, my Dad has spent his life working in construction. Even though we can’t see the interior, we can observe the process of restoration as well as see many of the Rotunda’s underlying structures exposed, which he finds very interesting.

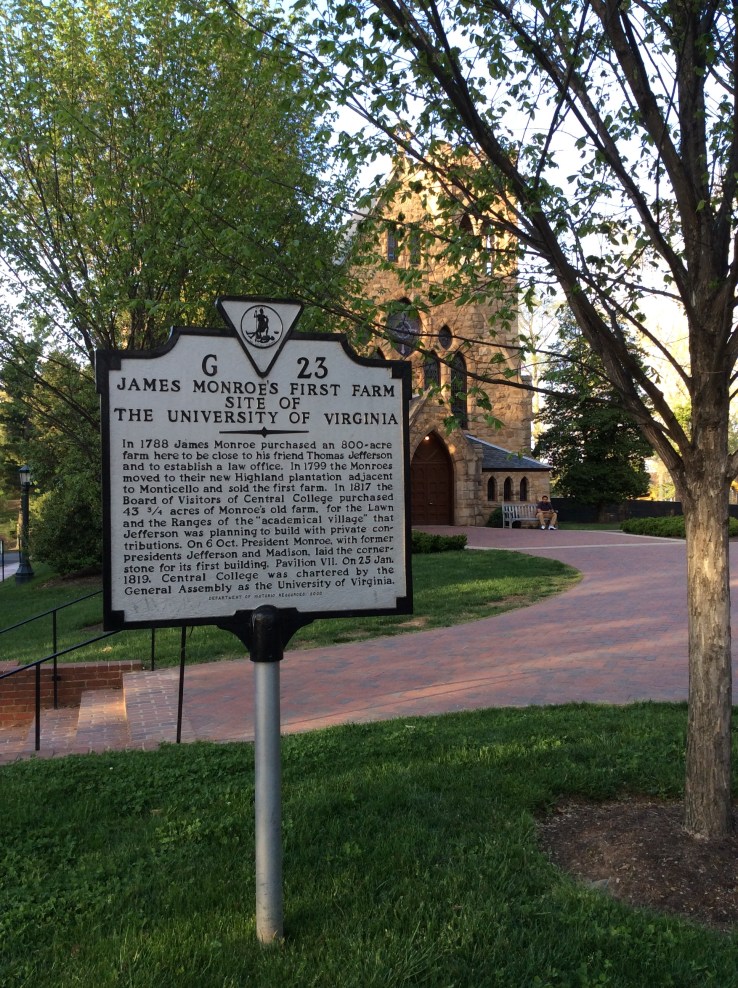

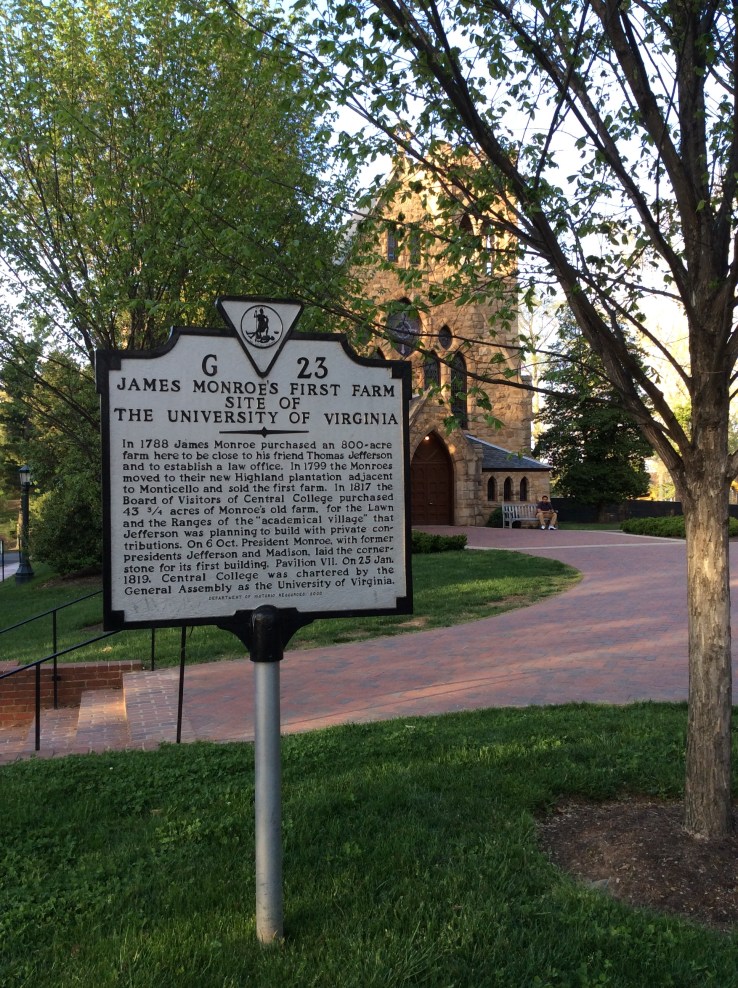

We learn various other interesting facts as we explore; there are historical markers aplenty throughout the college grounds. Part of the grounds of the University is located on the site of Jefferson friend and colleague James Monroe’s old farm, one sign explains. Another informs us that Edgar Allen Poe attended for one term in 1826, dropping out because his adopted father would not pay all of his debts. Imagine becoming so famous that briefly attending and dropping out of a prestigious university would earn you a historical marker there!

Dusk arrives, and it’s time to seek out dinner before the two-hour-plus drive back. It’s been an excellent day, and I couldn’t ask for better company. If you couldn’t tell already, I’m a bit of a daddy’s girl.

Thomas Jefferson’s lap desk, which he designed himself and on which he wrote the Declaration of Independence

Seventh day, April 25th.

The last day of my trip is dedicated to visiting museums with my Dad, and I put my project on hold for the time being. However, I return to the Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress with my Dad to show him around because I know he’ll absolutely love it. (He does.)

Presidential Souvenirs at the Smithsonian, including an early 1800’s snuffbox painted with Jefferson’s portrait at upper left

In the course of the day, we visit the National Museum of American History of the Smithsonian, where I make sure to visit the American Presidency gallery. I find some Jefferson artifacts among the collection, including the original portable desk on which he wrote the Declaration of Independence (which I already know is here, having visited the Smithsonian some years before), and a great little snuffbox from the early 1800’s painted with Jefferson’s likeness, which I don’t remember from my earlier visit.

There’s one more stop I do have to make before I finish my Jefferson tour. Of course, that’s the White House.

While he didn’t list his Presidency among his proudest accomplishments, Jefferson’s time in the White House significantly influenced the way the United States government would function in the future. Though he downsized the size of government following Washington and Adams’ Federalist administrations and reduced the national debt, he increased it again with the Louisiana Purchase and adopted Federalist (or in today’s terms, big-government) policies when he deemed it necessary for national security or the well-being of the nation as a while. He insisted on entertaining foreign dignitaries in a egalitarian and casual manner, with everyone free to seat themselves where they liked rather than being seated according to importance, and insisted on being addressed like any ordinary citizen, without honorific. The latter innovations, while initially shocking and offensive to European sensibilities, helped set the tone for American cultural egalitarianism as well as the spread of democracy in the centuries ahead, even if only in their tiny way.

While he didn’t list his Presidency among his proudest accomplishments, Jefferson’s time in the White House significantly influenced the way the United States government would function in the future. Though he downsized the size of government following Washington and Adams’ Federalist administrations and reduced the national debt, he increased it again with the Louisiana Purchase and adopted Federalist (or in today’s terms, big-government) policies when he deemed it necessary for national security or the well-being of the nation as a while. He insisted on entertaining foreign dignitaries in a egalitarian and casual manner, with everyone free to seat themselves where they liked rather than being seated according to importance, and insisted on being addressed like any ordinary citizen, without honorific. The latter innovations, while initially shocking and offensive to European sensibilities, helped set the tone for American cultural egalitarianism as well as the spread of democracy in the centuries ahead, even if only in their tiny way.

While Jefferson stooped to some shady political back-handedness during his bid for the presidency (estranging his friends John and Abigail Adams in the process), he struck the right tone in his First Inaugural Address in 1801 when he said ‘…Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle… We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.’ We could all use a little more of Jefferson’s rational, conciliatory idealism amidst the partisan bickering, conspiracy-theorizing, extremist, unkind rhetoric that over-saturates our public discourse today.

So ends the account of my Jefferson travels. But in following in his footsteps, learning more about his life and thought, and putting it all together in a narrative, many questions arose and trains of thought were initiated. There will be many more reflections on Jefferson to come in future essays, you can be sure of that.

*Listen to the podcast version here or on iTunes.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and Inspiration:

Brandt, Lydia Mattice. ‘The Architecture of the University of Virginia’

http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/University_of_Virginia_The_Architecture_of_the

Founders Online: Correspondence and Other Writings of Six Major Shapers of the United States,

Website. http://founders.archives.gov/

‘Gilbert Stuart’, article, National Gallery of Art website.

https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2005/stuart/washington.shtm

Hirst, K. Kris. History of Archaeology: The Series. About.com.

http://archaeology.about.com/od/historyofarchaeology/a/history_series.htm

Jacoby, Susan. Freethinkers: A History of American Secularism. New York: Owl Books, 2004.

http://us.macmillan.com/freethinkers/susanjacoby

Jefferson, Thomas. Writings. Compiled by The Library of America, New York: Penguin Books.

http://www.loa.org/volume.jsp?RequestID=67

Jenkinson, Clay. The Thomas Jefferson Hour. Podcast.

http://www.jeffersonhour.com/listen.html

Meacham, Jon. Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. New York: Random House, 2012.

http://www.jonmeacham.com/books/thomas-jefferson-the-art-of-power/

‘Short History of the University of Virginia’, University of Virginia website.

http://www.virginia.edu/uvatours/shorthistory/

‘Timeline of Jefferson’s Life’. Monticello.org. Website of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

http://www.monticello.org/site/jefferson/timeline-jeffersons-life

Zakaria, Fareed. In Defense of a Liberal Education. New York: W.W. Norton, 2015

http://books.wwnorton.com/books/In-Defense-of-a-Liberal-Education/

Claude-Adrien Helvétius, born on January 26th, 1715, is often credited with being a father of utilitarianism, or at least, for planting its philosophical seeds. Also an uncommonly egalitarian thinker for his time and place, he was born with a silver spoon in his mouth, perhaps filled with a tincture of some sort from time to time: Helvétius was the son and grandson of very wealthy physicians who ministered to royalty. Through these connections, Helvétius was appointed to a lucrative post as a tax collector and grew very wealthy when he was relatively young. By the time he was thirty-six and newly married, Helvétius had tired of courtly life, and retired to a country estate to take up a life of letters and scholarship.

Claude-Adrien Helvétius, born on January 26th, 1715, is often credited with being a father of utilitarianism, or at least, for planting its philosophical seeds. Also an uncommonly egalitarian thinker for his time and place, he was born with a silver spoon in his mouth, perhaps filled with a tincture of some sort from time to time: Helvétius was the son and grandson of very wealthy physicians who ministered to royalty. Through these connections, Helvétius was appointed to a lucrative post as a tax collector and grew very wealthy when he was relatively young. By the time he was thirty-six and newly married, Helvétius had tired of courtly life, and retired to a country estate to take up a life of letters and scholarship.

We pass through many other interesting and handsome rooms, including the parlor, lined floor to ceiling with portraits, again of Jefferson’s friends and influences. If I were to describe all the rooms in detail, this account would go on far too long, so I refer you to Monticello’s website’s excellent virtual

We pass through many other interesting and handsome rooms, including the parlor, lined floor to ceiling with portraits, again of Jefferson’s friends and influences. If I were to describe all the rooms in detail, this account would go on far too long, so I refer you to Monticello’s website’s excellent virtual

My Dad and I wander and chat, discussing what I had learned before the trip of the history of the University and its architecture. It also works out well that our visit coincides with the Rotunda building’s restoration, since, as aforementioned, my Dad has spent his life working in construction. Even though we can’t see the interior, we can observe the process of restoration as well as see many of the Rotunda’s underlying structures exposed, which he finds very interesting.

My Dad and I wander and chat, discussing what I had learned before the trip of the history of the University and its architecture. It also works out well that our visit coincides with the Rotunda building’s restoration, since, as aforementioned, my Dad has spent his life working in construction. Even though we can’t see the interior, we can observe the process of restoration as well as see many of the Rotunda’s underlying structures exposed, which he finds very interesting.

While he didn’t list his Presidency among his proudest accomplishments, Jefferson’s time in the White House significantly influenced the way the United States government would function in the future. Though he downsized the size of government following Washington and Adams’ Federalist administrations and reduced the national debt, he increased it again with the Louisiana Purchase and adopted Federalist (or in today’s terms, big-government) policies when he deemed it necessary for national security or the well-being of the nation as a while. He insisted on entertaining foreign dignitaries in a egalitarian and casual manner, with everyone free to seat themselves where they liked rather than being seated according to importance, and insisted on being addressed like any ordinary citizen, without honorific. The latter innovations, while initially shocking and offensive to European sensibilities, helped set the tone for American cultural egalitarianism as well as the spread of democracy in the centuries ahead, even if only in their tiny way.

While he didn’t list his Presidency among his proudest accomplishments, Jefferson’s time in the White House significantly influenced the way the United States government would function in the future. Though he downsized the size of government following Washington and Adams’ Federalist administrations and reduced the national debt, he increased it again with the Louisiana Purchase and adopted Federalist (or in today’s terms, big-government) policies when he deemed it necessary for national security or the well-being of the nation as a while. He insisted on entertaining foreign dignitaries in a egalitarian and casual manner, with everyone free to seat themselves where they liked rather than being seated according to importance, and insisted on being addressed like any ordinary citizen, without honorific. The latter innovations, while initially shocking and offensive to European sensibilities, helped set the tone for American cultural egalitarianism as well as the spread of democracy in the centuries ahead, even if only in their tiny way. Fourth day, April 22nd

Fourth day, April 22nd I’m heading to G Street between 9th and 10th,

I’m heading to G Street between 9th and 10th,

Jefferson and President George Washington held a contest for the design, but none of the original entries won. A later entry by a doctor was approved, and many of Jefferson’s classical design elements, especially those inspired by the Pantheon, were included.

Jefferson and President George Washington held a contest for the design, but none of the original entries won. A later entry by a doctor was approved, and many of Jefferson’s classical design elements, especially those inspired by the Pantheon, were included. It’s fitting that the largest private book collection of Jefferson’s time would become the seed collection of what’s now the largest library in the world. As for me, the LOC is my go-to source for published images in the public domain with which to illustrate my essays, as well as material for research.

It’s fitting that the largest private book collection of Jefferson’s time would become the seed collection of what’s now the largest library in the world. As for me, the LOC is my go-to source for published images in the public domain with which to illustrate my essays, as well as material for research.

After my first good, long gaze at the atrium and first floor hallway, a sign caches my eye, and I follow it to an exhibit which features the first published map of the United States.

After my first good, long gaze at the atrium and first floor hallway, a sign caches my eye, and I follow it to an exhibit which features the first published map of the United States.

The gallery at the southwest corner of the second floor is really what I’m looking for, and I head upstairs.

The gallery at the southwest corner of the second floor is really what I’m looking for, and I head upstairs.

The Jefferson Gallery holds what remains of the original Jefferson collection; about two-thirds of it was lost in a fire in 1851. The LOC is currently rebuilding the original collection, seeking out original copies, in sufficiently good condition, of the same books in the same edition that Jefferson originally collected, if they can be obtained.

The Jefferson Gallery holds what remains of the original Jefferson collection; about two-thirds of it was lost in a fire in 1851. The LOC is currently rebuilding the original collection, seeking out original copies, in sufficiently good condition, of the same books in the same edition that Jefferson originally collected, if they can be obtained.

I pore over the shelves for a good long while, then decide I needed to take a break and look at something purely decorative for a moment again while I walk around. I see a little crowd gathering and think, oh, yes, whatever it is, I’ll look at it too. It turns out it’s the line to get to the balcony that overlooks the Main Reading Room. Great. It was my plan all along to find out more about how I could access the collection and do some research. So I stand in line, get onto the balcony, and see a vaulted, domed library room, the most gorgeous I’ve ever seen. Through thick protective plexiglass.

I pore over the shelves for a good long while, then decide I needed to take a break and look at something purely decorative for a moment again while I walk around. I see a little crowd gathering and think, oh, yes, whatever it is, I’ll look at it too. It turns out it’s the line to get to the balcony that overlooks the Main Reading Room. Great. It was my plan all along to find out more about how I could access the collection and do some research. So I stand in line, get onto the balcony, and see a vaulted, domed library room, the most gorgeous I’ve ever seen. Through thick protective plexiglass. I return to Jefferson Building through the tunnel which shortcuts under the street (there was a little rain falling when I had left it earlier) and turn in all my things, except writing materials, to the coat check.

I return to Jefferson Building through the tunnel which shortcuts under the street (there was a little rain falling when I had left it earlier) and turn in all my things, except writing materials, to the coat check.