Margaret Sanger with Fania Mindell inside Brownsville clinic, forerunner of Planned Parenthood, Oct. 1916

Thursday, October 20th, 2016

I get out in decent time to start the day’s explorations, just after eight, but it’s not long before I realize I’m tired and hence, a little cranky. My friends and I watched the third Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump debate last night and some of the commentary which followed, then finally went to sleep very late after we talked about what we just watched, and other things. I’m mostly on New York time now, but not quite.

The abortion issue came up almost immediately in the debate since the first question from the moderator was about the Supreme Court and the appointment of justices. Trump pledged to nominate only strongly anti-abortion candidates. Clinton was adamant that Roe v. Wade and laws protecting women’s access to birth control and abortion (with appropriate limitations) be upheld. Clinton also strongly endorsed Planned Parenthood, praising the services it provides and criticizing all efforts to defund it. I, for one, am grateful to Planned Parenthood, the organization that Margaret Sanger founded. Like the women Sanger made it her mission to help, I needed health care that I could not yet afford when I was still in my late teens and early twenties. I found it at Planned Parenthood. I’m grateful to the warm and caring providers there, and I simply did not find what many of the organization’s opponents describe: a ruthlessly pro-abortion, anti-life organization. Instead, I met women who gave me wise and medically-correct advice on all aspects of women’s health, including ways to prevent the need for abortion. That’s entirely in keeping with Sanger’s mission. She was, in fact, anti-abortion, with certain qualifications.

201 and 207 E 57th St, Manhattan NYC, former site of the Bandbox Theatre

Adolph Phillip’s Fifty-Seventh Street Theater, later the Bandbox Theater, courtesy of Schubert Archives

I plan to head all the way to White Plains today, but as I’m preparing to buy the ticket at Grand Central Station, I pause to reconsider my day’s plans. In the end, I decide to put the trip on hold: it wouldn’t put my funds and time to best use since I was unable to discover the White Plains site location I sought at the New York Public Library yesterday. I’ll see if I’m more successful when I do more research tonight and perhaps go tomorrow. Instead, I decide to cover the northernmost Manhattan sites on my list after I hit up a few near the southwest end of Central Park that I didn’t get to yesterday.

I walk north towards Central Park and then east, and stop first at 205 E. 57th St near 3rd Ave where the Bandbox Theatre used to stand. Originally named Adolf Philipp’s Fifty-Seventh Street Theatre, the theater that became the Bandbox was built in 1912, closed in 1926, and demolished in 1969. Now there’s a Design Within Reach store and a high rise apartment building here.

On Feb 20th, 1916, Sanger and her supporters held a victory celebration at the Bandbox Theatre. The court had just dismissed the obscenity charges against her for publishing The Woman Rebel that had caused her to flee to Europe the year before. While she was away, many papers had begun to discuss birth control and sex a little more openly, and as you may remember, her daughter had just died suddenly the previous November, soon after Sanger’s return from Europe. Public opinion was swinging to Sanger’s side, and the court no longer had the appetite to pursue a case against her. What had once seemed a public defense against immorality would more likely be perceived as an attack on free speech and emerging modern, scientific attitudes about human sexuality. Even without the court case, however, the arrest and indictments proved an enormous boost to Sanger’s cause. She was portrayed, by herself as well as others, as a sort of free speech and humanitarian martyr, a persecuted champion of the cause of women, especially the poorest and most downtrodden.

14 E. 60th Street, Manhattan, New York City

Then I head northwest to 14 E. 60th St between 5th and Madison Aves. It’s a 13-floor building erected in 1903. Two restaurants, Rotisserie Georgette and Avra Madison Estiatorio, occupy the ground floor, and apartments above. Sanger had been staying at the Ambassador Hotel but moved to one of the apartments at this address on December 17, 1936. Her move here followed on the heels of the birth control movement’s victory in the Dec 7th decision in the One Package case, and not long before Sanger attended the Conference on Contraceptive Research and Clinical Practice that met at the Roosevelt Hotel which, as you may remember, I visited on my first day following Sanger here in New York City.

1935 and 1936 were busy years for Sanger. In addition to the One Package trial, she toured India, speaking to women’s groups and conferences and debating Gandhi there in December of 1935. She continued on to Hong King, then Japan. In Japan, she visited Tokyo’s fledgling birth control clinic founded by her Japanese counterpart Shidzue Ishimoto, and reviewed birth control methods that had been developed in that country since her 1922 visit. While the birth control movement was also beleaguered in that country by law and custom, many Japanese health care professionals were working on new and effective methods of birth control in that island nation where population growth was a constant and pressing concern. In 1932, she had met a Japanese physician at a birth control conference who had developed a new type of diaphragm. He had sent her that package which was intercepted in customs and led to the One Package case finally litigated three years later. She planned to continue her travels in China and Malaysia but had to cut her trip short due to recurring gallbladder trouble, then a broken arm. She stopped for a short visit in Hawaii, then returned to mainland U.S. to rest and recuperate.

The Plaza Hotel, Manhattan, New York City

I head west towards Central Park then veer south towards its southeast corner to 768 Fifth Ave at 59th St. Three occasions bring me here to the grand Plaza Hotel.

On March 15th, 1917, the National Birth Control League held a luncheon for her here in celebration of her release from Queens County Penitentiary. She had been imprisoned there for 30 days, convicted of violating anti-obscenity laws while operating her birth control clinic in Brownsville, Brooklyn.

Then from November 11th – 13th, 1921, the First American Birth Control Conference, organized by Sanger, was held here. The conference was widely attended by medical professionals, social scientists, humanitarians, authors, suffragists, socialists, and socialites. Its list of sponsors was likewise distinguished, including famed Parliamentarian and future Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Sanger gave the opening address, in which she called on the medical profession to join social workers and birth control activists in addressing the sexual dimensions of problems of hunger, poverty, and overpopulation. As she often pointed out, there were plenty of people working hard to alleviate poverty and disease, but there were very few paying attention to their primary root causes: the human need for love and sex. This was the conference which launched the future Planned Parenthood and concluded with the Town Hall event which turned into a police raid. Between the conference and the publicity following the raid, Sanger was firmly placed as the United States’, and indeed the world’s, preeminent birth control activist and spokesperson.

An interior view of the beautiful Plaza Hotel, Manhattan, NYC

Several years later, on February 26th, 1929, Sanger presided over a dinner promoting the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau. In her opening speech, Sanger outlined the history of her own birth control activism and the struggles and legal battles of the birth control movement in the United States from 1915 until that day. She also credited John Stuart Mill and Francis Place as founders of the modern birth control movement, about a century before her own activism began. Like Sanger, Mill was moved to support birth control by personal horror at the worst effects of children conceived in poverty: at age 17, he came across the corpse of a strangled infant discarded in a park. And like Sanger, Mill believed that when the poor had more children to help make money for the family, wages were inevitably driven down by the glut of laborers seeking employment, leading to a downward spiral of impoverishment and immiseration. So in 1823, young Mill and a friend distributed birth control pamphlets written by his father’s friend and social reformer Francis Place, and were arrested and imprisoned for their trouble.

The Park Lane Hotel (with the blue flags) and adjoining buildings

I walk a little ways west along the southern end of Central Park to 36 Central Park South, a.k.a. 59th St. Here at the Park Lane Hotel, Sanger delivered her speech ‘My Way to Peace’ to the New History Society on January 17, 1932. In my view, it’s a nasty speech. While Sanger generally insisted that birth control be entirely voluntary, the result of education and the right of women to have control over their own bodies, in this speech she called for coercive sterilization of ‘the unfit’. As Nazism was developed and implemented in the years to come, Sanger opposed it staunchly, sharply criticizing its racial doctrines and opposing its coercive practices. Though she justified it on the grounds of improving public health and decreasing mortality rates, to my mind she was never able to sufficiently explain how her earlier call in ‘My Way to Peace’ for coercive sterilization of ‘mental defectives’, people with certain diseases, and convicted criminals was morally superior to Hitler’s fascist system when it came to these unfortunate and marginalized groups.

New York Tribune, Fri Nov 18 1921, Announcement of Park Theater Margaret Sanger and Harold Cox appearance

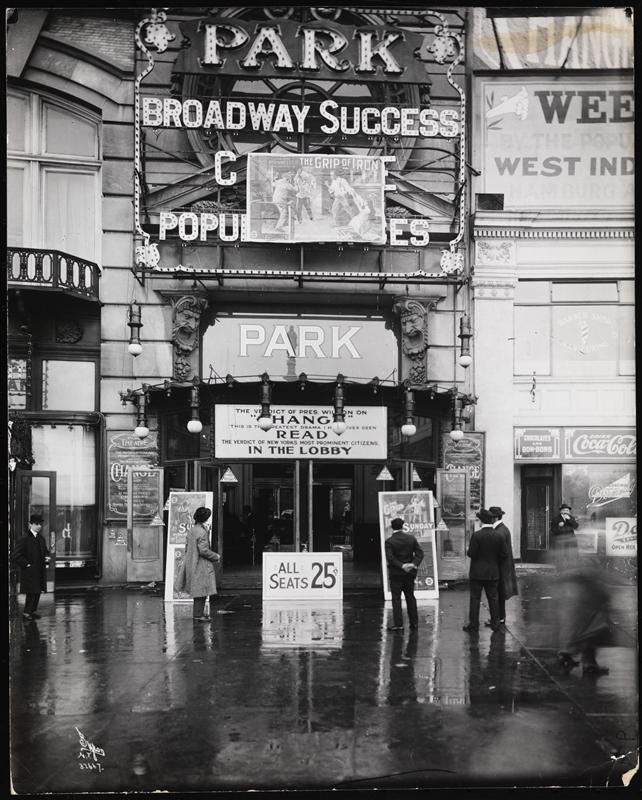

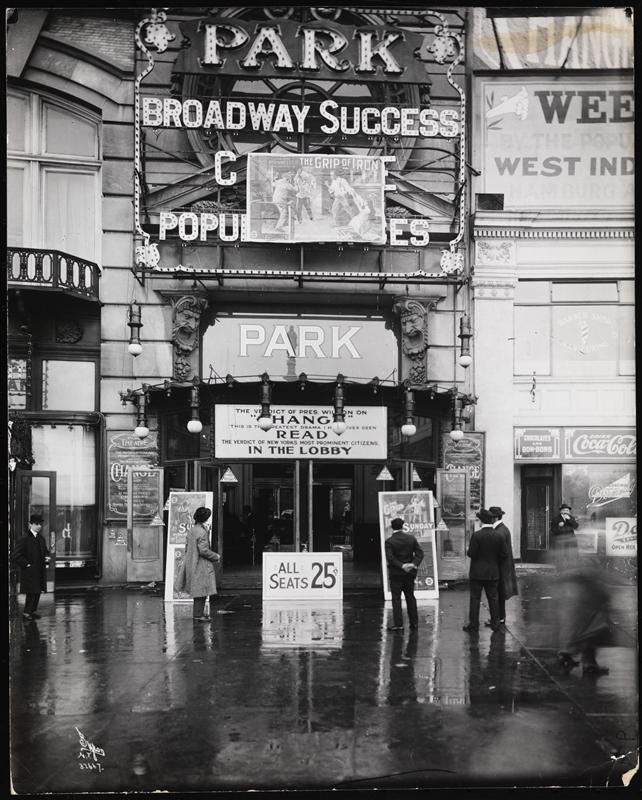

One place I miss on this trip is the former site of the nearby Park Theater, near the southwest corner of Central Park, where Harold Cox delivered the Sanger speech he was prevented from making at the Town Hall five days earlier. A New York Tribune announcement describes the location as ‘Columbus Circle near 59th and B’way’ (Broadway). As I consult the 1923 Bromley atlas I’ve been consulting for much of this series, I don’t find the Park Theater. Later, I search through an earlier edition of the Bromley Atlas and this time, I’m in luck. The Park Theater, renamed the Cosmopolitan Theater by 1923, was on 58th St, the second address to the west of Eighth Ave, its northeast corner at Columbus Circle at the southwest edge of Central Park. It stood where the Time Warner Center now faces onto 58th St, about where Google Maps identifies 322 W. 58th St.

In 1944, Sanger reminisced:

‘…Birth control, fifteen, twenty years ago was a lurid and sensational topic… The very term was one not mentioned in polite society, thanks to Anthony Comstock who had Congress classify it with “obscene, and filthy literature”… Our struggles lacked the dignity they have today. Back in 1921, Harold Cox, brilliant member of the English Parliament and Editor of the Edinburgh Review was to speak with me at that early forum of free speech, Town Hall. Our subject was “Birth Control: Is it Moral?”

Entrance of the Park Theater, formerly the Majestic, at Columbus Circle, photo courtesy of MCNY

With astonishing directness Roman Catholic Archbishop Patrick J. Hayes, through his emissary Monsignor Joseph P. Dineen, closed the meeting before it even opened. We had grown accustomed to opposition, from the combination of the Comstock group …with the Roman Catholic hierarchy, but never had the interference been so brutally direct before. Time and again theatres, ballrooms where I was to speak were ordered closed before the meeting could be held. In city after city this occurred during the years 1916, ‘17 and ‘18, but the climax was the now famous Town Hall incident which raised the issue throughout the country. Can one in public office use the power of that office to further his personal religious beliefs?

Mr. Cox and I were met at the steps of the Town Hall that evening by policemen, barred from entering and told, “There ain’t gonna be no meeting. That’s all I know…

We had the hierarchy to thank for so publicizing our meeting that the second held shortly after, at the big Park Theatre in Columbus Circle was packed fifteen minutes after a single door was opened. Two thousand people, many of whom had never heard of birth control before Cardinal Hayes gave it nation-wide publicity, stood outside clamoring to get in…”

I descend into the subway station at Columbus Circle and take the A train north, almost to the top of Manhattan Island. There are many sites on my list from Inglewood all the way back down to the southern end of Central Park, so I decide to visit them from north to south…

To be continued….

*Listen to the podcast version here or on Google Play, or subscribe on iTunes

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and inspiration:

‘14 East 60th Street‘, from 42Floors website

‘About Sanger: Biographical Sketch‘, from The Margaret Sanger Papers Project at New York University.

‘Another Look at Margaret Sanger and Race‘, Feb 23, 2012. From The Margaret Sanger Papers Project at NYU

‘Bandbox Theatre: East 57th Street near Third Avenue, New York, NY‘, International Broadway Database

Blake, Aaron. ‘The Final Trump-Clinton Debate Transcript, Annotated.’ Oct 19, 2016, The Washington Post: The Fix

Bromley, G.W. and Co. Atlas of the Borough of Manhattan, City of New York. Desk and Library edition, 1916, Plate 87 . Retrieved from Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division Digital Collection, The New York Public Library.

Bromley, G.W. and Co. Atlas of the City of New York, 1921 – 1923, Plate 82 and Plate 87. Retrieved from Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division Digital Collection, The New York Public Library.

Chesler, Ellen. Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992

Eig, Jonathan. The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2014.

Gopnik, Adam. ‘Right Again: The Passions of John Stuart Mill‘. Oct 6 2008, The New Yorker

Grimaldi, Jill. ‘The First American Birth Control Conference‘, Nov 12, 2010. The Margaret Sanger Papers Project at NYU

Guillin, Vincent. Auguste Comte and John Stuart Mill on Sexual Equality. Brill: Boston, 2009.

‘International Theatre: 5 Columbus Circle (W. 58th & 59th), New York, NY‘, International Broadway Database

‘Mrs. Sanger Glad She Was Indicted‘, New York Tribune, Feb. 21, 1916, p. 2, via The Margaret Sanger Papers Project, NYU

New-York Tribune, two selections from Nov 18, 1921, page 11: ‘Birth Control Appeal Fails to Move Enright‘ and ‘You Are Invited to Hear Margaret Sanger…‘ New York, New York. Via Newspapers.com

‘On the Road with Birth Control‘, Newsletter #21 (Spring 1999) of The Margaret Sanger Papers Project at NYU

Pokorski, Robin. ‘Mapping Margaret Sanger‘ from The Margaret Sanger Papers Project at NYU

Regan, Margaret. ‘Margaret Sanger: Tucson’s Irish Rebel.‘ Tucson Weekly, Mar 11, 2004.

Sanger, Margaret. ‘Birth Control: Then and Now,’ 1944, Typed Article. Source: Margaret Sanger Papers, Sophia Smith Collection

Sanger, Margaret. ‘Gandhi and Mrs. Sanger Debate Birth Control,’ Recorded by Florence Rose, published in Asia magazine, Vol. 26, no. 11, Nov. 1936, pp. 698-702

Sanger, Margaret. ‘My Way to Peace,’ Jan. 17 1932. From The Margaret Sanger Papers Project at NYU

Sanger, Margaret. Margaret Sanger, an Autobiography. Cooper Square Press: New York 1999, originally published by W.W. Norton & Co: New York, 1938

Sanger, Margaret. ‘Opening Address for Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau Dinner‘, Feb 26, 1929. Source: Margaret Sanger Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Margaret Sanger Microfilm S71:153.

Sanger, Margaret. The Pivot of Civilization, 1922. Free online version courtesy of Project Gutenberg, 2008, 2013

Sanger, Margaret. Woman and the New Race, 1920. Free online version courtesy of W. W. Norton & Company

In honor of Ernestine Louise Rose on the anniversary of her birth, January 13th, 1810

In honor of Ernestine Louise Rose on the anniversary of her birth, January 13th, 1810  In spite of many obstacles, Ernestine Rose was a renowned public speaker and debater in her own time, and especially acclaimed for her role among the preeminent leaders of the feminist movement. The abolitionist, socialist, pro-immigrant, Jewish, freethinker, and Paineite (devotees to the life and ideas of

In spite of many obstacles, Ernestine Rose was a renowned public speaker and debater in her own time, and especially acclaimed for her role among the preeminent leaders of the feminist movement. The abolitionist, socialist, pro-immigrant, Jewish, freethinker, and Paineite (devotees to the life and ideas of

![Garment workers, Webster Hall. Bain News Service, P. (ca. 1915) [between and Ca. 1920] [Image] Retrieved from the Library of Congress](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/garment-workers-webster-hall-bain-news-service-p-ca-1915-between-and-ca-1920-image-retrieved-from-the-library-of-congress.jpg)