On Calton Hill with Edinburgh’s Old City in the background.

It’s early Sunday afternoon, and I’m recovering from probably the single longest day of walking I’ve ever done, and that’s saying a lot for this avid hiker and walking enthusiast. My hip joints ache, my feet ache, my calves ache, my shins ache. But I don’t care, each of these aches are little tokens of a beautiful day. But let me back up a bit…

Saturday, May 03, 2014

I started my exploration of the Old City from the other end, where the Castle of Edinburgh overlooks all from its high perch on a craggy rock, along the Royal Mile, which heads east from the castle to Calton Hill and the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

The first half of my day is spent getting my bearings, creating a mental map of how the Old City hangs together, while spontaneously popping into any historic place that looked interesting. That can get expensive, paying entrance fees, but what the hell, it was my first day. Anyway, that’s what keeps these wonderful old places from falling into ruin or turning into tacky gift shops, so it’s worth every penny.) I have my little camera out to keep my hands free and snap a gazillion photos along the way. I don’t have a way to upload those photos and share them with you now, but I will when I get back home in a couple of weeks. The photos you see here are taken on my tablet.

So here I am, overlooking Edinburgh from Calton Hill.

It’s on Calton Hill that my journey following David Hume really begins, though I had looked into some sites associated with his life on the way, that I’ll return to later. It’s here on Calton Hill that he’s buried, and it’s here, I discover, that he caused the first path in Edinburgh to be built dedicated solely to the improvement of mind and body. Here, people would be encouraged to take their exercise by having a lovely place to walk, on this hillside with its spectacular views of the city, the surrounding countryside, and the Firth (estuary), away from the hustle and bustle, the crowds, the dirt, the unhealthy air, and the smells of the city. The first path to be built is named Hume Path in his honor, so of course, that’s the path I choose.

Hume Walk sign, Calton Hill, Edinburgh

David Hume’s grave monument, Calton Hill, Edinburgh, Scotland

I head back downhill a little from the park at the top of the hill, and Calton Hill Cemetery is on my left. I go through the gate and up the short flight of steps, and a bit ahead to my right, I find Hume’s elegant and rather simple monument and gravesite. I spend a good bit of time here musing: the power of physical objects to really bring things into focus still never fails to surprise me, and my sense of purpose in this journey to Edinburgh is strengthened.

I head back downhill a little from the park at the top of the hill, and Calton Hill Cemetery is on my left. I go through the gate and up the short flight of steps, and a bit ahead to my right, I find Hume’s elegant and rather simple monument and gravesite. I spend a good bit of time here musing: the power of physical objects to really bring things into focus still never fails to surprise me, and my sense of purpose in this journey to Edinburgh is strengthened.

I’ll soon write a reflection on his good and noble death…

Hume and Scottish soldier monuments at Old Calton Cemetery

I’m also moved to discover that a monument to Scottish-American soldiers was erected, featuring a statue of Abraham Lincoln. It seems to me so fitting that these two great heroes of freedom are honored here side by side, one of freedom of person, the other of thought.

When I leave Calton Hill, I return to the Royal Mile by an alternate route, with a detour along York Place to St. David’s Street. This street got its name from a fond prank by his close friend Nancy Orde, who wrote this little tribute in chalk on the side of Hume’s house. The street bears the name to this day.

My explorations are sure to bring me back to this street since Hume once lived here, so stay tuned. I’ll be back when I’ve gathered more details.

Statue of David Hume on the Royal Mile by Sandy Stoddart, 1995

I return to the Royal Mile and this time head west, passing by a grand statue of David Hume, across from St. Giles’ Cathedral. I’m not sure it looks anything like him based on all of his portraits I’ve seen, but it’s a handsome statue, very classical. This bronze Hume probably looks much better with his shirt off than the real man ever did; he was a portly and not terribly good-looking fellow, as much as I admire and respect him. But who knows? Perhaps the younger Hume was a little more fit, before the years of poring over books left him out of shape. The statue’s right toe is polished and very shiny, looks like it’s a tradition to rub his toe for luck.

Plaque in close leading to James’s Court, where David Hume lived for a time

James Court on the Royal Mile, Edinburgh

I return to James’s Court, where he lived for awhile in a tenement (apartment) with his sister. The original buildings are mostly gone, lost in a fire ages ago. I visited Gladstone’s Land and the John Knox house earlier in the day, two restored tenements from the era, and the Writer’s Museum, the restored home of Lady Stairs, built in 1622 and purchased and decorated by her in the 1700’s, all of which gives me a good idea of what Hume’s place would have looked like generally. James’s Court is a lovely little courtyard reached through a couple of lit

The old city is full of such little closes leading to pretty little courtyards or providing access to who knows where, all nearly irresistible to an American like me, where ancient cities are rare. Each time I see one of those closes, it looks like a little magic portal to some other place and time, and I just have to go through it. I spent much of my day stumbling on interesting corners of the city this way.

Tenements on the Royal Mile at Lawnmarket. ‘Tenements’ used to just refer to apartment buildings; the term gained its negative connotation later

On the other side of Lawnmarket (the same little neighborhood as James Court) is another stand of tenements across from the castle, in the area where Hume was born in 1711. The original buildings are also no longer there; while most of the tenements that stand today in old Edinburgh are old, most of them date from the mid-1700’s and later. Many of the original tenements were lost in fires, a common occurrence in those days when people depended on open flames for all light, heating, and cooking, and a fire that started in one place would quickly spread. Many of the others were torn down, since after Hume’s time, the tenements became the homes of the poor, where overcrowding and the accompanying disease and filth left them in very poor condition (people and buildings like).

I end my first day of Hume-seeking here, as I suddenly realize I’ve been walking for hours without eating. I eat a meal of the obligatory haggis (it’s delicious, even if it does sit a bit heavy; I suspect it’s not the haggis that the Scots of yore ate, which was boiled. This haggis does not appear to be prepared that way), and I wash down with a pint, of course.

It’s a typical Scottish spring day, cloudy and a little chilly, totally bearable to one used to San Franciso weather. It rains on me just a little during my walk back to my temporary home.

Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, entirely supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

‘Convulsions in nature, disorders, prodigies, miracles, though the most opposite to the plan of a wise superintendent, impress mankind with the strongest sentiments of religion; the causes of events seeming then the most unknown and unaccountable.’

‘Convulsions in nature, disorders, prodigies, miracles, though the most opposite to the plan of a wise superintendent, impress mankind with the strongest sentiments of religion; the causes of events seeming then the most unknown and unaccountable.’

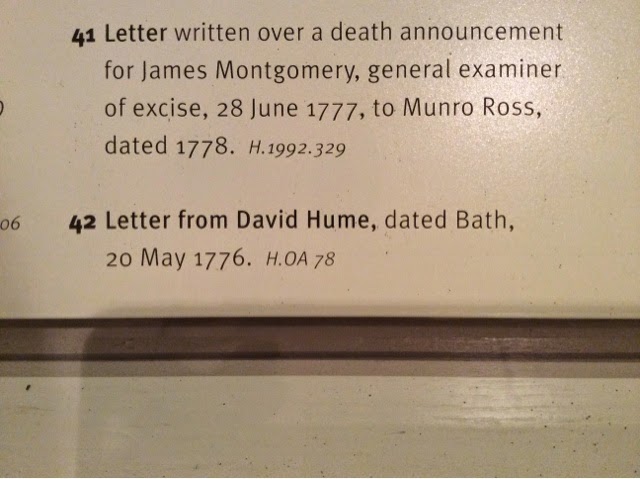

As the Scottish philosopher David Hume lay on his deathbed in the summer of 1776, his passing became a highly anticipated event. Few people in 18th-century Britain were as forthright in their lack of religious faith as Hume was, and his skepticism had earned him a lifetime of abuse and reproach from the pious, including a concerted effort to excommunicate him from the Church of Scotland. Now everyone wanted to know how the notorious infidel would face his end. Would he show remorse or perhaps even recant his skepticism? Would he die in a state of distress, having none of the usual consolations afforded by belief in an afterlife? In the event, Hume died as he had lived, with remarkable good humour and without religion.

As the Scottish philosopher David Hume lay on his deathbed in the summer of 1776, his passing became a highly anticipated event. Few people in 18th-century Britain were as forthright in their lack of religious faith as Hume was, and his skepticism had earned him a lifetime of abuse and reproach from the pious, including a concerted effort to excommunicate him from the Church of Scotland. Now everyone wanted to know how the notorious infidel would face his end. Would he show remorse or perhaps even recant his skepticism? Would he die in a state of distress, having none of the usual consolations afforded by belief in an afterlife? In the event, Hume died as he had lived, with remarkable good humour and without religion.

I’m sitting here in James Court, having a pint at the Jolly Judge, under a cozy little overhang, watching the rain fall all around me. It started out as a sunny day, with a brilliant blue sky with scattered big puffy white clouds, probably even a hot spring day by Scottish standards.

I’m sitting here in James Court, having a pint at the Jolly Judge, under a cozy little overhang, watching the rain fall all around me. It started out as a sunny day, with a brilliant blue sky with scattered big puffy white clouds, probably even a hot spring day by Scottish standards.

over to Calton Hill, to say farewell to the mortal remains of the great thinker I came here to discover in his hometown. As anyone would in my place, I feel deeply moved, my chest tight, my eyes prickly. Is there someone you deeply admire, where you’ve often felt that bittersweet ache that you so wish you could meet them, knowing you never could except through the artifacts, and more importantly, the words and ideas, they left behind? Then you know how I’m feeling just now.

over to Calton Hill, to say farewell to the mortal remains of the great thinker I came here to discover in his hometown. As anyone would in my place, I feel deeply moved, my chest tight, my eyes prickly. Is there someone you deeply admire, where you’ve often felt that bittersweet ache that you so wish you could meet them, knowing you never could except through the artifacts, and more importantly, the words and ideas, they left behind? Then you know how I’m feeling just now.

About ten minutes after I go inside, I hear the rain start to pour, and see the lightning flash through the skylight. I decide this would be a good place to linger ’till they close at five. And as soon as I leave, the rain abruptly stops, and I’m greeted to this spectacular sky again:

About ten minutes after I go inside, I hear the rain start to pour, and see the lightning flash through the skylight. I decide this would be a good place to linger ’till they close at five. And as soon as I leave, the rain abruptly stops, and I’m greeted to this spectacular sky again:

I’ve been tentatively planning to go to Chirnside, the place where Hume grew up. The house is no longer there, but the gardens are, and the place where the house was is well marked. The fares turn out to be quite expensive, and since the house isn’t there anymore, it seems a lot to pay since I’m traveling on the cheap. I decide to spend the money instead enjoying my remaining time in Edinburgh, immersed in the place, eating locally made delicious food. So I go and have some marvelous pastries at The Manna House instead, planning to visit Chirnside next time I’m here, hopefully on a bike tour.

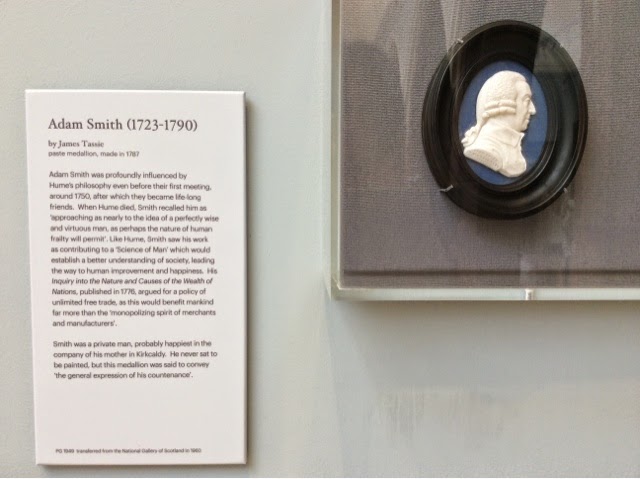

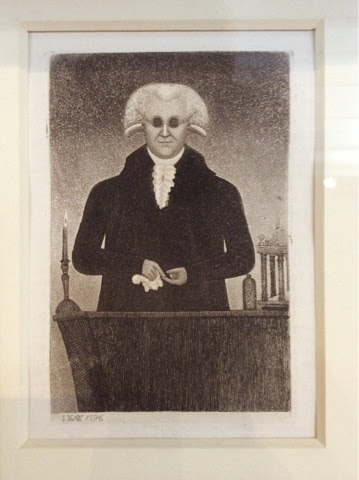

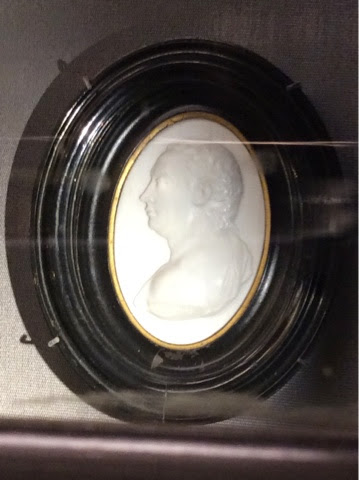

I’ve been tentatively planning to go to Chirnside, the place where Hume grew up. The house is no longer there, but the gardens are, and the place where the house was is well marked. The fares turn out to be quite expensive, and since the house isn’t there anymore, it seems a lot to pay since I’m traveling on the cheap. I decide to spend the money instead enjoying my remaining time in Edinburgh, immersed in the place, eating locally made delicious food. So I go and have some marvelous pastries at The Manna House instead, planning to visit Chirnside next time I’m here, hopefully on a bike tour. The last of the David Hume-related sites I visit today is the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. It’s even more beautiful than I expected, inside and out. Sculptures of Hume and his friend Adam Smith, philosopher and economist who wrote The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, adorn the southeast tower.

The last of the David Hume-related sites I visit today is the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. It’s even more beautiful than I expected, inside and out. Sculptures of Hume and his friend Adam Smith, philosopher and economist who wrote The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, adorn the southeast tower.

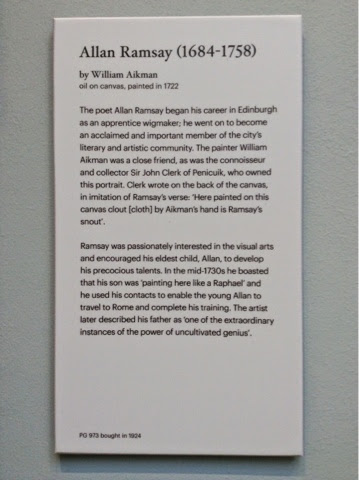

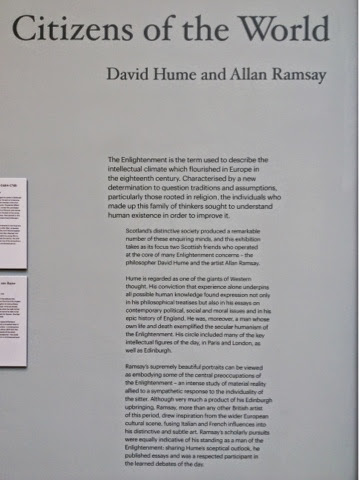

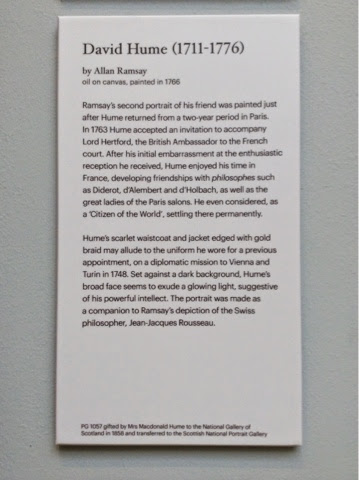

Here’s a little more about Allan Ramsey, David Hume, and the Scottish Enlightenment….

Here’s a little more about Allan Ramsey, David Hume, and the Scottish Enlightenment…. .

.

Thursday, May 08, 2014

Thursday, May 08, 2014

I head back downhill a little from the park at the top of the hill, and Calton Hill Cemetery is on my left. I go through the gate and up the short flight of steps, and a bit ahead to my right, I find Hume’s elegant and rather simple monument and gravesite. I spend a good bit of time here musing: the power of physical objects to really bring things into focus still never fails to surprise me, and my sense of purpose in this journey to Edinburgh is strengthened.

I head back downhill a little from the park at the top of the hill, and Calton Hill Cemetery is on my left. I go through the gate and up the short flight of steps, and a bit ahead to my right, I find Hume’s elegant and rather simple monument and gravesite. I spend a good bit of time here musing: the power of physical objects to really bring things into focus still never fails to surprise me, and my sense of purpose in this journey to Edinburgh is strengthened.