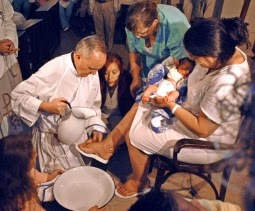

Like many, I’ve found myself pleasantly surprised and impressed by many of the sayings and doings of the new Pope. He emphasizes helping the needy and is critical of over-judgmentalism and of hyper-materialism (he practices what he preaches by driving a cheap car and living in a simple apartment). He also goes out of his way to spend time with ordinary people, be it in a correctional facility, in processions, or on the phone. Often dubbed ‘The People’s Pope’, he’s making the most of his promotion, on a mission to do real good in the world. Catholic or not, most people are thrilled that such an influential person is providing such an excellent example of how to live a life of service and of mercy.

Like many, I’ve found myself pleasantly surprised and impressed by many of the sayings and doings of the new Pope. He emphasizes helping the needy and is critical of over-judgmentalism and of hyper-materialism (he practices what he preaches by driving a cheap car and living in a simple apartment). He also goes out of his way to spend time with ordinary people, be it in a correctional facility, in processions, or on the phone. Often dubbed ‘The People’s Pope’, he’s making the most of his promotion, on a mission to do real good in the world. Catholic or not, most people are thrilled that such an influential person is providing such an excellent example of how to live a life of service and of mercy.

But I wasn’t quite as pleased the author of an article in the Huffington Post about Pope Francis’ first encyclical Lumen Fidei (The Light of Faith) co-authored with the previous Pope, Benedict XVI. The author says that the encyclical ‘…reflects Francis’ subtle outreach to nonbelievers’. While I consider myself an atheist, I’m a cultural Catholic, brought up with that religion. Since so many of my loved ones are observant Catholics and the Catholic church is so influential in the world, I’m very interested in what goes on in it. The first encyclical of a new Pope is a big deal, and this encyclical does a good job of promoting Catholic teaching with inspirational language and metaphors. However, the authors also resort to bad arguments to make their point. In many instances, they do so by contrasting their doctrines, for positive effect, against ‘straw man’ versions of non-believers’ views. In others, they set up false dichotomies, where they present Catholic doctrine as the only positive alternative to something bleak. I was disappointed that such educated and influential men, willfully or otherwise, so thoroughly mischaracterized attitudes and beliefs of secular people.

As I’m sure you know, a ‘straw man’ argument is the logical fallacy of first constructing a caricatured or artificial version of an opponent’s arguments, then attacking the false arguments in place of the real ones. A false dichotomy is a related fallacy, where the argument is presented as offering only two possible choices: the (arguer’s) favored position, or an opposing, usually unattractive or unbelievable one. While often effective in politics, these tactics are recognizable as a sign that the arguer finds themselves in a disadvantage. They might find that they can’t understand the arguments of his opponent, they might find that the opponent’s real arguments are so strong that they can’t find a way to answer them, or they might find that they’re worryingly attractive to others so they wish to obfuscate, misrepresent, or conceal them. The first two are less likely in this case as the authors are educated and articulate men. I think something like the latter is what’s going on here.

I also found that the encyclical promoted some worrying misconceptions about human beings, our nature and how we actually go about thinking, learning, being good, and finding meaning for ourselves. They describe human nature through the lens of a very narrow Catholic conception, which is to be expected, but they ignore, denigrate, or dismiss the validity of other accounts of human nature, informed by the sciences, the liberal arts, and other belief systems.

It’s especially clear from sections 2 and 3 that the Popes feel the Catholic Church is under attack by the scientific revolution, where evidence and reason are generally prized over tradition and belief. Perhaps this is the origin of the backlash against secularism and naturalism that’s characteristic of the poor arguments throughout the encyclical. The ways they present secular and atheistic thought is not new or unique to these men; they’re commonly held views, a fact very recently highlighted by Oprah Winfrey’s response to a self-professed ‘spiritual atheist’ interviewee. Yet the Popes could have offered a defense and promotion of their doctrines without the bad arguments, and their work would have been much better for it. It’s too bad that here again, the thoughts, motivations, beliefs, and characters of so many, in this case, naturalist, atheist, agnostic, and otherwise secular people, are misrepresented to such a large audience by influential men who I think should know better.

It’s true that there are some non-believers who are so, or become so, out of lack of interest, out of ignorance, or even simply to get out of following the rules of religion. But in my years of reading and research, I think the majority reject religion for worthy reasons. There are plenty of rational and moral reasons why people don’t believe in gods or a God as any religious tradition has conceived them or It. I think most secular people, from those who are personally believers of some sort but who value a society free of religious coercion, to the most ardent atheists, have done a lot of thinking on the matter, and this essay, I’m talking about these people. I’ll refer to them generally as secular thinkers, and to their musings as secular thought.

Here are some specific instances where I think the Popes got it wrong (there are plenty others). All quotes are from the encyclical ‘The Light of Faith’, in order of the sections they appear in, and my response follows directly after each:

From section 2:

‘Slowly but surely, however, it would become evident that the light of autonomous reason is not enough to illumine the future; ultimately the future remains shadowy… As a result, humanity renounced the search for a great light, Truth itself, in order to be content with smaller lights which illumine the fleeting moment yet prove incapable of showing the way. Yet in the absence of light… it is impossible to tell good from evil…’

There are many secular thinkers who feel that reason alone, the deliberative reflection on the nature of reality and what it means for the self and for humankind, is the only way people find truth and meaning. Yet more accept a more nuanced understanding, informed by the findings from more recent research in psychology, evolutionary biology, behavioral economics, and neuroscience. When we look closely at how we think and behave, we find that instinct and emotion play a huge role as well, and in fact, that reason is secondary to and cannot function without these. It’s that emotional part of us, where morality originates and the experience of transcending our individual selves takes place, that also leads us to discover truth, in the various ways it’s defined.

Secular people, too, realize this, and by renouncing religion or never joining one, it does not at all mean that they renounce the search for ‘the great light’ of truth. It’s more often the opposite: secular people make the choice to become or to remain free to search for truth without the often seemingly arbitrary limits of dogma. We can go where the evidence leads us, and we can say ‘what if?’ and ‘I don’t know’ without fear of retribution from an inscrutable God. We can give an account of good and evil based on what we learn about human nature and about the natural world as a whole. It could be argued, against Pope Francis, that if there is an unaccountable, unknowable, and unanswerable supernatural, conscious being force that creates and rules the world, it would be impossible to tell whether it was good or evil since whatever it says goes. In one era God could say it’s good to slaughter the infants of enemies (Ezekial, Isaiah), and in another era he might say it’s evil. This argument, often called divine command ethics, is an ancient one, and philosophers generally agree that a conception of the good must exist prior to determining whether something, God or otherwise, is good. It is, in short, not only possible, but necessary, to tell good from evil outside of the parameters of religion. That’s how you can recognize, in the first place, whether a religion is a good one.

Secular people, too, realize this, and by renouncing religion or never joining one, it does not at all mean that they renounce the search for ‘the great light’ of truth. It’s more often the opposite: secular people make the choice to become or to remain free to search for truth without the often seemingly arbitrary limits of dogma. We can go where the evidence leads us, and we can say ‘what if?’ and ‘I don’t know’ without fear of retribution from an inscrutable God. We can give an account of good and evil based on what we learn about human nature and about the natural world as a whole. It could be argued, against Pope Francis, that if there is an unaccountable, unknowable, and unanswerable supernatural, conscious being force that creates and rules the world, it would be impossible to tell whether it was good or evil since whatever it says goes. In one era God could say it’s good to slaughter the infants of enemies (Ezekial, Isaiah), and in another era he might say it’s evil. This argument, often called divine command ethics, is an ancient one, and philosophers generally agree that a conception of the good must exist prior to determining whether something, God or otherwise, is good. It is, in short, not only possible, but necessary, to tell good from evil outside of the parameters of religion. That’s how you can recognize, in the first place, whether a religion is a good one.

From 8 and 10:

‘Faith opens the way before us and accompanies our steps through time. Hence …we need to follow the route it has taken… Here a unique place belongs to Abraham, our father in faith. Something disturbing takes place in his life: God speaks to him… Abraham is asked to entrust himself to this word.’

The story of Abraham and his son Isaac is a strange one to the secular thinker, and not at all a good example for showing how faith is linked to the search for truth. In this story, God demands Abraham do something considered evil by just about any human being, secular or religious, from Abraham’s time to our own: to murder his son. All the while this God is knowing he doesn’t really mean it! Where’s the love of truth here? The sort of faith this deity demanded was the same sort of faith demanded of the suicide bomber, or the parent who denies life-saving medicine to their child because they belong to a faith-healing sect. It’s the sort of faith, that of the blind worshiper, that is deeply alien to one who seeks to understand what they do before they do it, and why they do it, while simultaneously demanding personal accountability from themselves and others.

It’s the ultimate anti-personal-responsibility fable, and was among the earliest religious tales that alerted me to the problems of faith.

From 13:

‘The history of Israel also shows us the temptation of unbelief to which the people yielded more than once. Here the opposite of faith is shown to be idolatry…Idols exist, we begin to see, as a pretext for setting ourselves at the centre of reality and worshiping the work of our own hands. Once man has lost the fundamental orientation which unifies his existence, he breaks down into the multiplicity of his desires… his life-story disintegrates into a myriad of unconnected instants.’

This is also a very strange section to a secular thinker. The opposite of faith, the philosopher, the logician, the linguist would say, is non-faith, which precludes worship of anything at all. 13 is a long section of false dichotomies as well as straw man arguments. The thinker who learns from the world itself, through history, biology, psychology, astrophysics, and so on, learns that the universe, humankind, and the self are not a disorienting haze of ‘unconnnected instants’. Things are interconnected and form marvelous patterns throughout the universe, from the forming of stars, elements, galaxies, planets, and solar systems in the cosmos through various forces, to the transition from instinct-only to simpler forms of intelligence to consciousness in the story of human evolution, to the fascinating development over time from simple hunter-gatherers in small groups to complex societies, cultures, beliefs, and knowledge-gathering systems. The history of human thought reveals that human beings, from prehistoric times, throughout history, and up to now, from innocent of religion to pagan to religious believer, have been engrossed with understanding the cosmos, from the blazing sky to the deepest mysteries of their own minds, and all the while have demonstrated rigor and discipline while on their quest for knowledge. Religion is just one of the many human products of that quest.

This is also a very strange section to a secular thinker. The opposite of faith, the philosopher, the logician, the linguist would say, is non-faith, which precludes worship of anything at all. 13 is a long section of false dichotomies as well as straw man arguments. The thinker who learns from the world itself, through history, biology, psychology, astrophysics, and so on, learns that the universe, humankind, and the self are not a disorienting haze of ‘unconnnected instants’. Things are interconnected and form marvelous patterns throughout the universe, from the forming of stars, elements, galaxies, planets, and solar systems in the cosmos through various forces, to the transition from instinct-only to simpler forms of intelligence to consciousness in the story of human evolution, to the fascinating development over time from simple hunter-gatherers in small groups to complex societies, cultures, beliefs, and knowledge-gathering systems. The history of human thought reveals that human beings, from prehistoric times, throughout history, and up to now, from innocent of religion to pagan to religious believer, have been engrossed with understanding the cosmos, from the blazing sky to the deepest mysteries of their own minds, and all the while have demonstrated rigor and discipline while on their quest for knowledge. Religion is just one of the many human products of that quest.

From 19:

‘…The attitude of those who would consider themselves justified before God on the basis of their own works. Such people …are centred on themselves… Those who live this way, who want to be the source of their own righteousness, find that the latter is soon depleted and that they are unable even to keep the law. They become closed in on themselves and isolated …their lives become futile and their works barren…’

This section is focused on a debate within the larger community of believers, but I include it here because of what it implies about those who look to human nature and to their own instincts to find the impetus for goodness. It implies here that human nature, on its own, is essentially isolationist rather than altruistic. By doing so, it ignores nearly everything we know today about human psychology and behavior, about evolution, neuroscience, economics, and so on. Human beings are essentially social with an individualistic streak, and without deeply rooted instincts toward cooperative, generous behavior, we are weak, nearly defenseless against predators and the forces of nature, and are imprisoned by and even defeated in the pursuit of our own shortsighted needs. Goodness and kindness are accounted for with or without religion.

From 25:

‘In contemporary culture…truth is what we succeed in building and measuring by our scientific know-how, truth is what works and what makes life easier and more comfortable… But Truth itself, the truth which would comprehensively explain our life as individuals and in society, is regarded with suspicion… In the end, what we are left with is relativism, in which the question of universal truth …is no longer relevant.’

This section is problematic to begin with in the way that it seems to work with a definition of Truth narrowly defined within the parameters of Catholic doctrine, and from there proclaiming that people no longer care about Truth, just facts about the world that can lead us to make useful products. But people all over the world of no faith or any religious faith, throughout time, have demonstrated restless curiosity and boundless energy in trying to find out the truth about reality, from the most prosaic little problem in everyday life (how can I save time carrying water from the well?) to the greatest mysteries of the universe (what are the stars made of, and do they move on their own or do the gods push them around?). This is as true today as it ever was, regardless of the fact that some people (and I would agree, too many) are overly concerned about personal comfort at any cost and how much nice stuff they can amass for themselves.

It’s also problematic in that this section appears to imply that placing a high value on ‘what works’ leads people to care nothing about what’s truly enriching. The scientist, the naturalist, indeed anyone who finds the universe an utterly fascinating and meaningful thing on its own terms might find this idea very strange. Applying a test of ‘workability’, in fact, shows a great deal of respect for truth, in that the seeker takes great pains to make sure that personal bias, incomplete or misleading information, too small a sample size, etc. are not a source of error. If a theory or received dogma doesn’t ‘work’, doesn’t adequately account for the facts, doesn’t coherently explain how and why something is as it is, or doesn’t successfully make predictions, then, they know, the search for truth must continue.

From 35:

‘Because faith is a way, it also has to do with the lives of those men and women who, though not believers, nonetheless desire to believe and continue to seek. To the extent that they are sincerely open to love and set out with whatever light they can find, they are already, even without knowing it, on the path leading to faith. They strive to act as if God existed, at times because they realize how important he is for finding a sure compass for our life in common or because they experience a desire for light amid darkness, but also because in perceiving life’s grandeur and beauty they intuit that the presence of God would make it all the more beautiful.’

Here, the Popes make the most underhanded move to undermine secular people. They resort to a particularly transparent sort of fallacious argument along the lines of: ‘You’re saying (that), but I know what you’re really thinking, you’re thinking (this), and here’s why (this) is wrong’. This is simply a dishonest argument, and potentially insulting in a most unphilosophical way. The honest philosopher does their best to understand the argument of their opponent, consider it as it if might be true, and then argue against it on its own merits if she disagrees; they do not pretend as if it’s really something else. They do this sneakily, using the phrase ‘those…who’, so that there’s an out: this does not necessarily include the entire class of nonbelievers. But reading carefully, they also set it up so that no one could tell which nonbelievers it includes, since the nonbelievers themselves, ‘without knowing it’, really want to be believers somewhere deep down. So just as easily, they could be referring to all believers, or to none, though presumably they’re referring to some quantity in between. But this doesn’t work. If one is actually a non-believer, it seems incoherent to say that they could also be one who believes that a God is necessary for meaning and beauty. Unless you’re talking about a nihilist of a particular variety. Yet this can’t be so, because they’ve already added the caveat that they are also ‘sincerely open to love’. So either this section is entirely contradictory in its attempt to outline the true nature of believers (at least some), or it’s a veiled attempt to deny that there are really any unbelievers out there. Circular reasoning strikes again.

From 43:

‘Children are not capable of accepting the faith by a free act, nor are they yet able to profess that faith on their own; therefore the faith is professed by their parents and godparents in their name.’

Years back, when my grandfather began to notice that he never saw me at church anymore, he asked me if I was still going. When I said no, he said that that wasn’t acceptable: the promise my parents made for me at my baptism obligated me to go. I said little at the time, being in my late teens and still not comfortable with challenging my grandfather directly. But I was very annoyed at what I thought a most ridiculous notion: that anyone could make this sort of binding promise on another’s behalf.

But that’s not the worst of it: my grandfather was also making the same point the Popes make in this encyclical, that parents can proclaim tenets of faith on behalf of their child. But faith, or belief, is not something that can be simply transferred or put on, like a family heirloom or a piece of clothing. It’s the natural assent of the mind to the matter-of-factness of propositions or circumstances. True, you can ‘fake it ’til you make it’, engaging in a sort of cognitive-behavioral exercise where you decide ahead of time what you want to be true, then make a habit of acting as if it is, then come to believe it. Perhaps the Popes have this sort of thing in mind in this passage, though they don’t describe it that way. But to the secular thinker, this sort of belief-inducement is not an honest one, since it can be used to instill belief in anything at all. Rather, keeping an open mind to the evidence and allowing belief to emerge naturally in response is a much better method if you don’t want to be misled. When the Catholic religion of my early youth no longer offered meaningful, believable answers to so many of my questions, I felt angry at the time, feeling that I had been raised in a bubble, led to assent to all kinds of things without having the relevant information. ‘Faith’ became almost a dirty word for me, as it began to sound more and more as if it really meant something more like indoctrination or even brainwashing. So in the end, raising us to believe only in the strict ‘Truth’ of Catholic teaching without being allowed to question, and without introducing other possible answers, resulted in the opposite of its intended effect.

From 54:

‘Thanks to faith we have come to understand the unique dignity of each person, something which was not clearly seen in antiquity. …Without insight into these realities, there is no criterion for discerning what makes human life precious and unique. Man loses his place in the universe, he is cast adrift in nature, either renouncing his proper moral responsibility or else presuming to be a sort of absolute judge, endowed with an unlimited power to manipulate the world around him.’

I don’t know entirely know how the Popes feel justified making this claim. While it’s true that Bible-based religions caused many converts and believers throughout history to behave much better than they did before or might have otherwise, the opposite is also true. Sometimes it inspired the Christians to have mercy on their enemies, sometimes it led them to torture and kill ‘heretics’, slaughter Jews in pogroms, and to enslave and murder black people and Native Americans. Some may say that people who behave this way are not really of the ‘true faith’, but their actions are justifiable according to certain Biblical principles and commandments. In the Old Testament, unbelievers are to be put to death (and what are Jews and Native Americans to Christians if not unbelievers?). In the New Testament, Jesus says that the fate of towns who don’t accept his disciples’ teaching will be like that of Sodom and Gomorrah, where God put everyone to death (Matthew 10: 13-15, Genesis 19). It seems that, here, the worth of human life is actually often contingent in the Bible, on ‘good behavior’ or on whether they profess the right religion, and not always of value in its own right.

In antiquity, in fact, there were many cultures and belief systems that did place human life and dignity on as high or even higher a plane than did the ‘faithful’ of the Old and New Testaments. Ancient Egyptian literature, the Code of Hammurabi, the Epic of Gilgamesh, and some philosophies and religions of ancient India and Greece, for example, advocate such principles as non-violence and the worth and dignity of the human person, and place strict limitations on harming and killing other human beings, and indeed, other living things that are not human beings. Many of these ideas and belief systems are religious, but many are not.

In antiquity, in fact, there were many cultures and belief systems that did place human life and dignity on as high or even higher a plane than did the ‘faithful’ of the Old and New Testaments. Ancient Egyptian literature, the Code of Hammurabi, the Epic of Gilgamesh, and some philosophies and religions of ancient India and Greece, for example, advocate such principles as non-violence and the worth and dignity of the human person, and place strict limitations on harming and killing other human beings, and indeed, other living things that are not human beings. Many of these ideas and belief systems are religious, but many are not.

Secular thinkers such as myself find no trouble deriving firm principles and morals from the natural world, and in fact find that taking moral responsibility demands rejecting religious dogma in favor of an understanding of how human nature works and what the actual circumstances require. We don’t find ourselves ‘adrift’ since human morality is based on the social instincts, expanded and universalized through reason, and we’re all in this world to sink or swim together, ultimately. We also don’t consider ourselves ‘absolute judges’. Instead, we hold ourselves accountable not only to ourselves but to each other, to democratic principles, to the consideration of the rights of other people, and to the limits and strictures of the universe itself. In fact, it’s unquestioning acceptance of dogma that can look, to the secular thinker, very much like reneging on one’s moral responsibility.

In sum, the authors of this encyclical and secular thinkers find themselves in agreement on many particular issues, and in disagreement on others. (Of course, I don’t speak for all secular thinkers just as the Popes don’t represent every belief of all individual Catholics. Instead, I represent my own views and those I find generally promoted by secular thinkers who write about philosophy, morality, the physical sciences, psychology, political and legal theory, and the humanities.) Respect for individual rights, a commitment to promoting human health and happiness, justice, equality of opportunity, and so on, are universal human concerns, and have been throughout recorded history, from the atheistic to the pious.

Fortunately, in his public speeches and behavior, Pope Francis I publicly emphasizes the best of his humanistic principles with little or no disparagement of those who do not believe in these principles for the same underlying reasons. In this, I think the good example he provides will far outweigh his theological publications when it comes to his broader influence in the world. But it’s worth having the discussion about the nature of inherited faith versus evidenced-based belief, until secular thought is no longer maligned by those who fear and mistrust it because of the kind of misrepresentation this encyclical exemplifies.

Ordinary Philosophy and its Traveling Philosophy / History of Ideas series is a labor of love and ad-free, supported by patrons and readers like you. Please offer your support today!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources and inspiration:

Pope Francis I. Lumen Fidei (On The Light of Faith). Encyclical letter, June 29th, 2013

I’ve just finished Frans De Waal’s excellent new book, which is a combination of a popular science exploration of primatology and the origins of human morality, and a critique of the ‘New Atheist’ movement. De Waal, a nonbeliever himself (as a scientist, he finds the question of whether or not God exists ‘uninteresting‘), nevertheless finds the confrontational style of the New Atheist movement ill conceived, counterproductive, and probably futile.

Bosch’s painting, De Waal thinks, actually reveals his humanism, the idea that the human race is naturally good and worthy of admiration in it own right. The figures frolicking in the garden in the center panel enjoy the best that the world has to offer, especially the joys of one another’s company. The figures being punished in the hell of the right panel, revealingly, are not being punished for sins against religion. Rather, they have trangressed the moral laws pertaining to just and fair treatment of one another, such sins as greed, gambling, and cheating, and those pertaining to the proper care and comportment of our own bodies, such as gluttony and drunkenness.

Bosch’s painting, De Waal thinks, actually reveals his humanism, the idea that the human race is naturally good and worthy of admiration in it own right. The figures frolicking in the garden in the center panel enjoy the best that the world has to offer, especially the joys of one another’s company. The figures being punished in the hell of the right panel, revealingly, are not being punished for sins against religion. Rather, they have trangressed the moral laws pertaining to just and fair treatment of one another, such sins as greed, gambling, and cheating, and those pertaining to the proper care and comportment of our own bodies, such as gluttony and drunkenness.

Like many, I’ve found myself

Like many, I’ve found myself  Secular people, too, realize this, and by renouncing religion or never joining one, it does not at all mean that they renounce the search for ‘the great light’ of truth. It’s more often the opposite: secular people make the choice to become or to remain free to search for truth without the often seemingly arbitrary limits of dogma. We can go where the evidence leads us, and we can say ‘what if?’ and ‘I don’t know’ without fear of retribution from an inscrutable God. We can give an account of good and evil based on what we learn about human nature and about the natural world as a whole. It could be argued, against Pope Francis, that if there is an unaccountable, unknowable, and unanswerable supernatural, conscious being force that creates and rules the world, it would be impossible to tell whether it was good or evil since whatever it says goes. In one era God could say it’s good to slaughter the infants of enemies (Ezekial, Isaiah), and in another era he might say it’s evil. This argument, often called divine command ethics, is an

Secular people, too, realize this, and by renouncing religion or never joining one, it does not at all mean that they renounce the search for ‘the great light’ of truth. It’s more often the opposite: secular people make the choice to become or to remain free to search for truth without the often seemingly arbitrary limits of dogma. We can go where the evidence leads us, and we can say ‘what if?’ and ‘I don’t know’ without fear of retribution from an inscrutable God. We can give an account of good and evil based on what we learn about human nature and about the natural world as a whole. It could be argued, against Pope Francis, that if there is an unaccountable, unknowable, and unanswerable supernatural, conscious being force that creates and rules the world, it would be impossible to tell whether it was good or evil since whatever it says goes. In one era God could say it’s good to slaughter the infants of enemies (Ezekial, Isaiah), and in another era he might say it’s evil. This argument, often called divine command ethics, is an  This is also a very strange section to a secular thinker. The opposite of faith, the philosopher, the logician, the linguist would say, is non-faith, which precludes worship of anything at all. 13 is a long section of false dichotomies as well as straw man arguments. The thinker who learns from the world itself, through history,

This is also a very strange section to a secular thinker. The opposite of faith, the philosopher, the logician, the linguist would say, is non-faith, which precludes worship of anything at all. 13 is a long section of false dichotomies as well as straw man arguments. The thinker who learns from the world itself, through history,  In antiquity, in fact, there were many cultures and belief systems that did place human life and dignity on as high or even higher a plane than did the ‘faithful’ of the Old and New Testaments. Ancient Egyptian literature, the Code of Hammurabi, the Epic of Gilgamesh, and some philosophies and religions of ancient India and Greece, for example, advocate such principles as non-violence and the worth and dignity of the human person, and place strict limitations on harming and killing other human beings, and indeed, other living things that are not human beings. Many of these ideas and belief systems are religious, but many are not.

In antiquity, in fact, there were many cultures and belief systems that did place human life and dignity on as high or even higher a plane than did the ‘faithful’ of the Old and New Testaments. Ancient Egyptian literature, the Code of Hammurabi, the Epic of Gilgamesh, and some philosophies and religions of ancient India and Greece, for example, advocate such principles as non-violence and the worth and dignity of the human person, and place strict limitations on harming and killing other human beings, and indeed, other living things that are not human beings. Many of these ideas and belief systems are religious, but many are not.