I’ve long been obsessed with ideas and arguments, why people do and say the things they do, why people believe what they do, and so forth., as I’ve already discussed in an earlier piece. This curiosity and drive to understand, at least a little, the workings of the universe outside my own mind has not diminished over the years in the slightest. So a few years ago, when the job market dried up, my business partially failed, and my artistic pursuits provided me with much satisfaction but little income, I decided to more fully immerse myself in one of my greatest loves, philosophy, by going back to college.

It was a dream of mine that I had never seriously pursued in my early youth, though I eagerly attended junior college as soon as I was able. In my family, the goal of pursuing higher education was not discussed much. Most of my closest relatives are honest, hardworking people, generally blue-collar, hand-on work, and that was for the most part true of myself too, though I worked more in customer service jobs that had some sort of idealist or artistic element. I also have a strong affinity for blue-collar work, and really enjoyed the physically labrious aspects of my long-time intermittent job at a salvage yard.

Many of my relatives were and are suspicious of much of higher education too, seeing it as an array of dangerous temptations away from a life immersed in a particularly conservative brand of religious faith. Also, as a woman, higher education was less of a priority in my family. I felt it was always implied, but rarely said outright, that a good girl got married and stayed at home, perhaps after a stint at junior college, even a bachelor’s degree maybe, before settling in to homemaking while still young enough to make lots of babies. That’s it, unless I wanted to become a nun. All that sounds like a lovely, happy, fulfilling life for many, and I am fortunate to be a fond and proud auntie and cousin many, many times over precisely because so many women in my family find this lifestyle right for them. But never felt right for me, and over the years, I felt annoyed and a little resentful that other options were never discussed or encouraged, and that I never had a mentor intellectually. But I also realize that I may very well be unfair in this assessment. For one thing, my dad and other close family members never resented my constantly badgering them with questions and were always willing to answer them fully, and one of my dear uncles and I regularly engage in honest, no-holds-barred. lengthy debate and discussion to this day, and I thank him for that. It was also really entirely up to me to stop gadding around and instead of gleefully following my whims, to focus on the goal of completing a degree, applying the creativity I applied to other pursuits to the task of fundraising for school.

But why not keep all this to myself? Why have I taken this previously mostly internal process and dumping it out into the world? (With the full realization that few, at this point, even read this stuff.) I’ve often gotten the sense that philosophers, amateur and professional, are usually irritating to most other people besides fellow philosophers, and even these pick on each other at least as often as they engage in fruitful debate. (At least, it appears so from the public discourse, but my evidence for this is merely anecdotal.) But I think that this sense of philosophy being this annoying form of snobbery is based only on the archness with which some philosophers deliver their musings, and on a particular perception of what philosophy is. Many professional philosophers display a seemingly protectionist attitude toward their craft, preferring to share their ideas mostly or only with other professionals in highly arcane language. (Arcane: mysterious, secret. Arcane language: jargon) I actually think that this largely closed-off, rarified realm of philosophy is invaluable: it’s a place where ideas can be invented and pursued as far as they can go, by a community entirely devoted to this task. The untold riches that have emerged from this level of discourse is wonderful astounding. I just wish I and most of the public had the ability to fully understand and appreciate it, and the bit I’ve had the good fortune to experience left me amazed and entranced, and humbled.

But I also think that everyone, or almost everyone, engages in philosophical thinking of one sort or another, hence my blog’s byline. We not only react in moral matters but often make some sort of attempt to justify them to others. We all seek to describe or define, at times, the essential nature of reality. When it comes to aesthetics, to visual art and music and literature, we try to add a description of the idea(s) or driving force behind them, placing them within a context, rarely letting works of art speak entirely for themselves. Every one of us who has engaged in conscious reflection on anything has done some philosophy.

When it comes to writing and applying this sort of thinking, curiously enough, I’m almost entirely drawn to most areas of philosophy except philosophy of art. It seems kind of weird for a person who’s always been immersed in the arts, who has been drawing, sewing, sculpting, and so forth, and who loves music, for a lifetime. I think it’s because I do happen to be the sort of artist who likes to let my art speak for itself, and if I try to politicize or contextualize it, than it loses its immediacy and power for me. I’d rather let others do that, to read into my artwork whatever they’re compelled to read into it, or to discover some truths about me that I can’t since I lack the objectivity. But philosophy of science and of law, political and metaphysical, and most of all, moral philosophy… those I just can’t get enough of. And as I touched on in the aforementioned piece I wrote a month or so ago, I’ve been thinking on these things outside of academia for so long that I’m still far more comfortable doing philosophy in laypersons’ terms. But I still need that sharing and expressing of ideas without which a fuller understanding is impossible.

So I keep thinking about how the universe works, based on the information I receive about what’s going on in the world, and keeping writing about the process of figuring it out because it’s fascinating to me for its own sake. But not only that. I really feel a sense of deepest connection to the human family in its entirely, and feel a deep sense of responsibility towards it and gratitude to it. For me, that means I don’t feel satisfied simply by expressing my instinctive reactions to the occurrences and ideas I encounter in the world, such as simple anger, or disgust, or joy, or love. That’s because I don’t feel an isolated individual whose thoughts, feelings, and actions are as worthwhile or interesting on their own as they are within the larger realm of shared human experience.

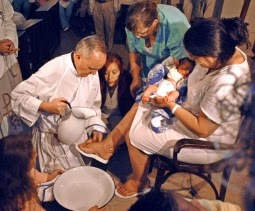

For example, the blaming, the finger-pointing, the shaming I see going on in the public sphere over political matters seems like a giant room with a lot of people screaming and no one listening, because too many people forget that their ideological opponents are people with needs and interests and beliefs too. I feel the need to explore and explain what’s behind all this as well as expressing righteous approval or indignation because I feel that the screaming is not only not accomplishing anything, it’s just not that interesting, and reveals little about the world besides a very narrow set of facts about human psychology. I think that when we remember to sit back and reflect on why we feel and believe as we do, and patiently explain ourselves in an honest manner, with a generous spirit of always assuming the best of motives in your ideological opponent, it’s only then that we are justified in our beliefs, and have earned the right to feel that we are, indeed, in the right. But of course, this must always be provisional, because as it so happens, so one has all the needed information at any one time to know everything about everything. We must always be ready to acknowledge when we’ve been wrong, and always be ready to learn.

I look forward to what I will continue to learn from all of you out there, and always welcome your thoughts and your honest debate!

![Woman writing, Gerard ter Borch [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/f7781-woman2bwriting252c2bgerard2bter2bborch2b255bpublic2bdomain255d252c2bvia2bwikimedia2bcommons.jpg?w=292&h=400)