In a recent essay, ‘But My Brain Made Me Do It!‘, I argue that many attempts to evade or minimize personal responsibility for one’s actions are misguided. The concept of personal responsibility exists not only to impart personal and societal meaning to human behavior, but to assign accountability. After all, if human beings can not be required to fulfill responsibilities or make retribution for harms done, societies could not function and group living would be impossible. Many attempts to evade personal responsibility only consider the reasons why one might easily have acted one way or another, and ignore two other key factors which lend weight and force to it in the first place: whether the person could have acted otherwise, and whether the person was in fact the one who performed the action. Therefore, attempts to isolate only deliberate intention, and to disregard other factors in matters of personal responsibility, undermine the nature and utility of the whole concept.

In a recent essay, ‘But My Brain Made Me Do It!‘, I argue that many attempts to evade or minimize personal responsibility for one’s actions are misguided. The concept of personal responsibility exists not only to impart personal and societal meaning to human behavior, but to assign accountability. After all, if human beings can not be required to fulfill responsibilities or make retribution for harms done, societies could not function and group living would be impossible. Many attempts to evade personal responsibility only consider the reasons why one might easily have acted one way or another, and ignore two other key factors which lend weight and force to it in the first place: whether the person could have acted otherwise, and whether the person was in fact the one who performed the action. Therefore, attempts to isolate only deliberate intention, and to disregard other factors in matters of personal responsibility, undermine the nature and utility of the whole concept.

In the United States, debates about the meaning and ramifications of personal responsibility surround not only crime and punishment issues, but also public policy dealing with collective action problems, such as pollution, overpopulation, gun control, defense, law enforcement, and access to health care. These types of problems result from individual choices en masse, so that personal responsibility may be difficult to assign to any one individual. Yet, these problems would not exist unless all of those individuals choose to act they way they do. Collective action problems affect so many people, are so complex, and are so expensive, that a solution to them requires mass participation: many individuals each required to take part in solving the problem.

Yet solutions are often difficult to find because of the personal responsibility problem: how do we hold particular people responsible for solving a collective action problem when their individual choice is merely a ‘drop in the bucket’, so to speak? If personal responsibility is so narrowly conceived that one is only held responsible when there is a clear and direct link from the act in question to the entirely of the consequence, and they that they must have (mostly) understood the consequence of their action beforehand, than we must allow that no-one can be held responsible for most collective actions problems. But if we take a more robust view, that people can be held responsible for what they do and the consequences that flow from it, even if the consequences cannot be foreseen or intended, then we do have the right to call on the community to do what they can to fix the problem, be it through contributions of money or effort, through reparations, through accepting (just) punishment, or through other means.

In my ‘Brain’ essay, many of my arguments supporting a robust view of personal responsibility are consistent with a typically American conservative viewpoint, though some of my conclusions relating to particular public policies may differ. (For example, when it comes to criminal justice, I favor a reparative/restorative system over a punitive one, and restraint over zeal in enforcement of all but the most serious crimes, but those are topics for other essays.) When I apply the same arguments to collective action problems, however, the result is more consistent with a progressive approach to public policy as well as to morality.

A robust view of personal responsibility, I find, entails that individuals are morally obligated to contribute, through taxes or otherwise, to programs that preserve and promote the health, protection, and basic well-being of society as a whole. I argue this for two reasons: one, it is individual choices, be it in the aggregate, that create collective action problems (I address this issue in a past essay, in my example of the Dust Bowl crisis in mid-century United States, where the individual decisions of farmers to ‘get rich quick’ created a crisis for everyone, including those others who decided to farm more prudently and responsibly.) Therefore, members of a society should contribute to solutions or to make reparations, for the harms to others that result, directly or indirectly, as a result of their choices, Secondly, individuals, as well as society as a whole, often enjoy wealth, comfort, improved health, and other benefits that are derived from the reduced circumstances of others. A robust view of personal responsibility would also require that those who enjoy these benefits should pay their fair share for them when they have not adequately contributed for them otherwise (for example, in the marketplace).

Consider the issue of health care, and the debate over whether it should be publicly subsidized.

A typically American conservative position on this issue is that health care should be a free market commodity, because it should be a reward for honest work and its contribution to society. If one is personally responsible for their own actions, then if they do their fair share and work hard, they earn the right to access health care. The market is the mechanism, therefore, that limits the access to health care only to those people who have contributed to society through work. People who do not do their fair share, on the other had, should not get health care as a freebie, coercively paid for via taxation, by wage earners. If people feel like freely donating health care to the poor, fine and good, but they should not be forced to do so.

I sympathize with that position to a limited degree. I now work in the health care industry and see people who I have good reason to believe are gaming the system, quite often, in fact. (I address this issue in another recent essay.) If some people are cheating the system, I agree, they oftne are doing the wrong thing, but, I think, not necessarily. Consider this example: a pair of aging parents find their nest egg, carefully scrounged together through a lifetime of hard work, suddenly threatened by the wife’s recent diagnosis of breast cancer. These parents may be faced with this set of choices a) let the wife die without treatment, b) pay for the treatment, wiping out the life savings with which they would have paid for their retirement and the care of their children c) hide their assets to access free public health care assistance. These parents may feel justified making the third choice, since they feel that their primary moral duty is to save the life of their spouse and to care for their children, that their lifetime of hard work contributed enough to society to earn the moral right to this public assistance, and that they do little wrong gaming a system made corrupt and expensive by greed and political chicanery. I, for one, would find it difficult to condemn such a choice, and in some circumstances, may agree that it’s the most morally justifiable choice.

In my work in the medical office as well as in my years in the work force, I’ve seen far more examples of situations that bear a closer resemblance to the hypothetical situation I presented (closely inspired by a real life one) than to simple cheating out of greed or laziness. I work for a good doctor, who is the only local one in his specialty to see low-income patients on public health care assistance. (The reimbursement rates from many public health care assistance programs are very, very low, and physician’s offices have a hard time keeping their doors open at all if they accept many patients with that insurance.) Therefore, our office cares for many of the working poor as well as the suspected cheaters. Every day, I see elderly people who carry the signs of their past lifetime of hard work as well as people who currently work long, hard hours for little pay, whose health care is paid for through taxation because they can’t afford it otherwise. And I think: that’s how it should be.

That’s because all of us enjoy the benefits that come from the hard work of so many low-income people. We get to eat plentiful, cheap food because other people toil long hours with little pay in fields, restaurants, and factories. We get to wear comfortable, well-made clothing and stuff our wardrobes to a degree that no-one but the wealthiest of aristocrats used to enjoy, again, because others work in miserable, boring, depressing conditions working practically for nothing. I live in Oakland’s Chinatown, where I am surrounded by the hardest-working people I’ve seen in my life, other than the (largely immigrant and children of immigrant) people I worked with in the food industry, and these people, too, receive pitiful remuneration for the vast contributions they make to your life and mine.

When you and I pay a few cents for an apple, or a few bucks for a shirt, or a couple hundred for a computer, we do not pay our fair share, to my mind. The market may have driven prices and wages down, but when we’ve purchased those things, we’ve only fulfilled our part of the bargain between the buyer and the seller. We have not, however, fulfilled our personal responsibility towards all those other people who made our wealth possible. We have paid for our own life of comparative wealth and ease in an exchange that buys a life of privation for another.

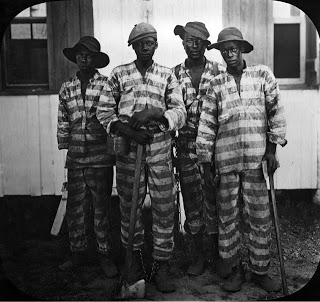

So when you and I buy that cheap apple, that cheap shirt, that cheap computer, our decision to do so creates an economic situation in which many other people earn poor wages. And those poor wages, in turn, mean that people can’t afford to buy health care, or indeed, enjoy those benefits of society that their work makes possible in the first place. In the long run, it’s our fault, even if indirectly, that other people can’t buy health care, because this situation arises as a consequence of our own choices, our own actions. And this is only one example in which individual actions cause collective action problems. Other examples are pollution, overpopulation, natural resource depletion, systematic racism, traffic jams…. The list goes on and on.

So here’s a question with which I would challenge those who don’t like to feel responsible, or to hold other people responsible, for such collective action problems, including so many American conservatives: why is it that you should be personally responsible for your economic well-being by choosing to do your part and work hard, but you should not be held personally responsible for the consequences of your choices in the marketplace for others who work hard? As an example we’ve already considered shows, we can follow the chain of consequences readily from our own market choices to their collective impact on the lives of others. People, out of self-interest, choose to pay less for food if they can, usually without questioning why it’s cheap. But for food to be cheap, it’s generally because wages are low (in combination with improved technology, which can increase efficiency; but sometimes, new technology means workers have to compete with it, again lowering wages). Individual choices to buy cheaper produce cause wages to be low: they benefit from the reduced circumstances of others. And healthcare, even in more efficient, less corrupt systems than ours, tends to be expensive, because of the high cost of the education of doctors and of research and development, and because it’s labor intensive (each doctor’s visit often requires a significant input of time to be effective), so low wage earners usually cannot afford adequate health care. Therefore, our personal decision to buy cheap produce causes many others not to be able to afford health care. Why, then, would we not be held to any level of responsibility for the consequences of our actions when it comes to access to health care?

We already accept the idea of personal responsibility for individual contributions to collective action problems in many other areas of life. In order to enjoy the legal right to drive, for example, we’re required to purchase driver’s insurance. That’s because our own decision to drive can have debilitating and fatal consequences for others, even if they are entirely accidental. Almost no-one intends to maim or kill another when getting behind the wheel, yet we accept that when we choose to drive, we are still personally responsible, in one way or another, for what happens as a consequence. We also accept that since we desire and enjoy such benefits and freedoms as the right to go our way unmolested by other people, to vote, to travel on public roads and bridges, and so on and so forth, we are responsible for contributing to those institutions that solve collective action problems, and contribute to the maintenance of the military, the police, infrastructure, legal system, and so forth, thorough our tax contributions and otherwise.

As intelligent social creatures, human beings have conceived and developed societies organized according to and supported by robust conceptions of personal responsibility, demonstrated by such human products as morality and law. Instead of operating primarily from a ‘me and mine’ outlook, the most successful and long-lasting, and I argue, the happiest persons and societies operate from a predominantly ‘us and ours’ mentality, with the ‘me and mine’ enjoying even greater benefits than pure self-interest could produce. (The earliest Christian communities adopted this influential philosophy and practice, with great success and to their great credit; consider the tale of Ananias, who, out of greed, did not contribute the same percentage as others towards the welfare of all. Contrast this with the later incarnations of the Church, which retained the rhetoric and abandoned the practice of equal personal responsibility for, and equals enjoyment of, the public good.)

In sum, a robust view of personal responsibility leads us to act more responsibly in our day to day actions and, in turn, to generally behave in such a way that has the best outcomes. We come to act as Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative would have us do, to ‘Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law’. When each of us realizes that our day to day actions often have not only immediate and personal but wide-reaching consequences, our behavior changes. And when we wish that the consequences of our actions are beneficial or at the least not harmful, our behavior changes for the better, our imagination expands, and the world becomes a richer and safer place for us all.

In thinking recently about the nature of government and its proper roles, I recalled this Fareed Zakaria piece about Singapore’s engineered diversity.

In thinking recently about the nature of government and its proper roles, I recalled this Fareed Zakaria piece about Singapore’s engineered diversity.

personal responsibility: if we do wrong, we pay the price. A central feature of our justice system, after all, is the right to a fair

personal responsibility: if we do wrong, we pay the price. A central feature of our justice system, after all, is the right to a fair

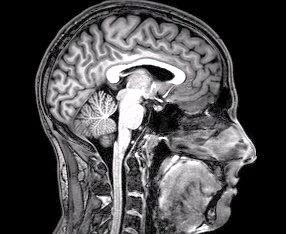

There’s a common idea which leads many people (myself included) to instinctively excuse our own or others’ less-than-desirable behavior because we were under the sway, so to speak, of one or another mental state at the time. This is illustrated especially clearly in our justice system, where people are routinely given more lenient sentences, given the influence of strong emotion or of compromised mental health at the time the crime was committed. “The Twinkie Defense” is a(n) (in)famous example of the exculpatory power we give such mental states, where Dan White claimed that his responsibility for the murder of two people was mitigated by his depression, which in turn was manifested in and worsened by his addiction to junk food. We routinely consider ourselves and others less responsible for our wrong actions if we’ve suffered abuse suffered as children, or because we were drunk or high at the time, or we were ‘overcome’ with anger or jealousy, and so on.

There’s a common idea which leads many people (myself included) to instinctively excuse our own or others’ less-than-desirable behavior because we were under the sway, so to speak, of one or another mental state at the time. This is illustrated especially clearly in our justice system, where people are routinely given more lenient sentences, given the influence of strong emotion or of compromised mental health at the time the crime was committed. “The Twinkie Defense” is a(n) (in)famous example of the exculpatory power we give such mental states, where Dan White claimed that his responsibility for the murder of two people was mitigated by his depression, which in turn was manifested in and worsened by his addiction to junk food. We routinely consider ourselves and others less responsible for our wrong actions if we’ve suffered abuse suffered as children, or because we were drunk or high at the time, or we were ‘overcome’ with anger or jealousy, and so on.![Atticus and Tom Robinson in Court, By Moni3 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ordinaryphilosophy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/02561-atticus_and_tom_robinson_in_court.gif?w=383&h=291)